Phonological Memory and Implications for the Second Language Classroom

There is mounting evidence that phonological memory (PM), a sub-component of working memory, is closely related to various aspects of second language (L2) learning in a variety of populations, suggesting that PM may be an essential cognitive mechanism underlying successful L2 acquisition. This article provides a brief critical review of the role of PM in the L2 context, examines the issue of trainability associated with PM, and discusses pedagogical techniques that may facilitate or enhance PM function in the L2 classroom. Communicative classrooms, as a result of their emphasis on oral input, place heavy processing demands on PM. The authors argue that more recourse to audio-lingual activities and reliance on written and visual support, including text-supported oral input, may help to offset the burden on PM and enhance L2 learning, particularly for individuals with low PM capacity.

Il est de plus en plus manifeste que la mémoire phonologique (MP), une sous-composante de la mémoire de travail, est étroitement liée à différents aspects de l’apprentissage d’une langue seconde (L2) chez diverses populations, ce qui suggère que la MP peut être un mécanisme cognitif essentiel à la réussite de l’apprentissage d’une langue seconde. Le présent article offre un résumé critique du rôle de la MP dans le contexte L2, examine la question de l’aptitude à la formation associée à la MP, et discute des méthodes pédagogiques pouvant faciliter ou améliorer la fonction MP dans une classe L2. En particulier, les auteurs font valoir que les classes communicatives, parce qu’elles sont axées sur la communication orale, imposent une charge intensive à la MP lors du traitement, et que le fait d’avoir davantage recours à des activités audio-orales et de se fier plus globalement à un support visuel et écrit, y compris la communication orale à l’aide d’un texte, peut aider à réduire la pression sur la MP et permettre alors d’améliorer l’apprentissage de la langue seconde, en particulier pour les personnes ayant une faible mémoire phonologique. [End Page 371]

phonological memory (PM), second language learning, individual differences

mémoire phonologique, apprentissage d’une langue seconde, différences individuelles

Second language (L2) teachers have long observed that learners vary enormously in both their rate of learning and their ultimate achievement levels. A number of factors are thought to contribute to such individual variation, including instructional context (e.g., Wesche, 1981), the degree and type of motivation learners bring to the classroom and its tasks (e.g., Clément, Dornyei, & Noels, 1994; Gardner, Tremblay, & Masgoret, 1997; Noels, 2001; Oxford & Shearin, 1994), and the age at which instruction begins (e.g., Johnson & Newport, 1989; Oyama, 1976). Working memory (WM), and in particular phonological memory (PM), has increasingly been linked to success in various aspects of L2 acquisition across research settings, including the classroom.

Although recent L2 research with both children and adults suggests that PM may play a direct role in the development of vocabulary (e.g., French, 2006; Service & Kohonen, 1995) and grammar skills (e.g., French & O’Brien, 2008; Williams & Lovatt, 2005), as well as in oral fluency (e.g., French, 2009; O’Brien, Segalowitz, Collentine, & Freed, 2006; O’Brien, Segalowitz, Freed, & Collentine, 2007), there has been a notable lack of review of existing research on the relevance of PM to L2 teaching. This brief review is an attempt to fill this gap by evaluating evidence for the relationship between PM and L2 learning and by discussing possible implications for the L2 classroom.

Phonological memory and L1 acquisition

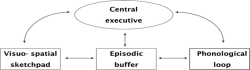

Current views consider working memory to be a limited-capacity system responsible for the simultaneous storage and processing of information in real time, such as takes place during the comprehension of verbal material. One crucial sub-component of working memory is often referred to as phonological memory. (Other terms found in the literature include verbal short-term memory, phonological working memory, phonological short-term memory, and phonological loop.) Phonological memory has been considered to play a prominent role within the highly influential working memory framework developed by Baddeley and colleagues (e.g., Baddeley, 1986; Baddeley & Hitch, 1974), which views working memory as consisting of several components (see Figure 1): (1) a central executive, an attention control [End Page 372] system responsible for integrating information from different working memory subsystems and long-term memory, allocating resources, and overseeing basic working memory operations; (2) the phonological loop, responsible for the temporary maintenance of acoustic- or speech-based material; (3) the visuo-spatial sketchpad, which handles visual images and spatial information; and (4) an episodic buffer, involved in the binding of information from subsidiary systems and long-term memory into a unitary episodic representation (Baddeley, 2000).

The phonological loop, considered to sub-serve phonological memory, has been by far the most examined working memory subsystem and is thought to be largely responsible for the temporary maintenance of acoustic- or verbal-based information. In the phonological loop system, encoded information or representations are believed to decay rapidly—usually within two seconds—unless rehearsed subvocally.

Phonological memory has been highlighted as a potentially important source of individual differences in information processing in first language (L1) acquisition (for reviews, see, for example, Baddeley, 1986; Baddeley, 1996; Gathercole & Baddeley, 1993) and in second language (L2) learning (Gathercole & Thorn, 1998; Harrington & Sawyer, 1992; Papagno, Valentine, & Baddeley, 1991).

Multi-component working memory model (sources: Baddeley, 1986, 2000; Baddeley & Hitch, 1974)

Typical tasks used to measure PM include digit- and word-span tasks, requiring repetition of sequences of digits or words. It has been pointed out, however, that such tasks reflect knowledge of already familiar items and therefore include input from long-term memory (Gathercole & Baddeley, 1993, p. 48). To lessen the contribution of long-term memory, a non-word repetition task is more often used, in which participants are asked to repeat non-words of [End Page 373] various syllable lengths. Other tasks involving non-words, such as non-word span and serial non-word recognition, have also been used as a measure of PM. The non-words generally consist of semantically empty items that follow the phonotactic structure of real words (e.g., ‘bannifer,’ ‘thickery,’ ‘stopograttic’). Some studies indicate a correlation between such tasks and vocabulary development in young children (Adams & Gathercole, 1996; Avons, Wragg, Cupples, & Lovegrove, 1998; Gathercole & Baddeley, 1989; Gathercole, Willis, Emslie, & Baddeley, 1992). Findings in these studies suggest that PM supports the long-term learning of new sound patterns and, as such, is closely linked to L1 vocabulary acquisition.

Although a robust relationship has been reported between non-word repetition tasks and L1 vocabulary learning, some studies employing these tasks appear to indicate that PM may play a declining role in L1 vocabulary development from as early as five years (Gathercole & Baddeley, 1989; Gathercole et al., 1992). Gathercole and Baddeley (1989) reported that PM predicted vocabulary development between four and five years old, while the reverse relationship was reported in the five- to six-year-old period. This decreasing effect of PM involvement in older children has been attributed to the increasing role played by long-term phonological and lexical knowledge as a child’s vocabulary grows.

However, it appears that while contributions from PM to vocabulary learning generally decrease as a function of increased vocabulary size in older children (see also Jarrold, Baddeley, Hewes, Leeke, & Phillips, 2004), they do not disappear altogether. In one study, Gathercole and her colleagues (Gathercole, Service, Hitch, Adams, & Martin, 1999) found a correlation between phonological memory skill and vocabulary knowledge in children as old as 13, although the size of the correlation was smaller than that usually reported with young children. This suggests that PM may remain important for individuals whose lexical knowledge is well beyond the early stages of development.

Phonological memory and L2 acquisition

Paralleling the focus on the phonological loop found in the L1 literature, research has also examined the role of PM in L2 learning in a variety of experimental settings. Overall, the research findings are generally positive, pointing to a specific role for PM in L2 acquisition with children and adults across various levels of L2 proficiency. [End Page 374]

In particular, Service’s (1992) longitudinal study reported a strong relationship between PM (as measured by non-word repetition) at the start of English instruction and the performance of Finnish-speaking elementary school children on tests of reading and listening comprehension as well as written production nearly three years later. In a follow-up study over a longer period, Service and Kohonen (1995) found that the relationship between PM (again non-word repetition) and L2 tasks such a reading comprehension was evidence of a specific relationship between PM and vocabulary acquisition. Applying a similar longitudinal design, Dufva and Voeten’s (1999) study showed that both native language literacy and phonological memory had positive effects on foreign language (English) learning when Finnish-speaking Grade 1 students were later examined on English listening comprehension and active vocabulary skills at the end of Grade 3. Together, the findings from these and other developmental studies (e.g., French, 2006) point to PM as a strong predictor of L2 achievement, particularly vocabulary acquisition, during the early school years.

Other studies have reported a direct link between PM and children’s vocabulary development (Masoura & Gathercole, 1999, 2005); however, the extent of the relation is not always clear. For example, Masoura and Gathercole (1999) found significant correlations between both L1 (Greek) and L2 (English) vocabulary measures and non-word repetition tasks in each language in 8- to 11-year-old children. Since the children had already received an average of three academic years of English language study, it is likely that they had already gained some familiarity with English phonotactics and word structure. It is difficult to determine, therefore, to what extent the association found in this study between high English vocabulary scores and high performance on the English-based non-word repetition task consisting of items with a high degree of ‘wordlikeness’ may be attributed primarily to students’ pre-existing familiarity with English.

In intensive ESL programs, PM has also been directly linked to children’s actual L2 improvement in both vocabulary (productive and receptive) and grammar skill (morphosyntactic knowledge). Using non-word repetition tasks, French (2006) examined the PM of French-speaking elementary school children at the start of a five-month intensive ESL program and found that PM strongly predicted increases in individuals’ ability to understand and use new vocabulary at the end of the program, even after taking into account the effects of general intelligence, school motivation, and prior L2 skill. In a subsequent study with ESL intensive learners, French and O’Brien (2008) [End Page 375] investigated the relationship between PM and performance on a discrete-point grammar test designed to assess knowledge of the morphosyntactic structures (tense, aspect, inflections, negation, question form, adjective order, and possessive determiners), that are typically covered in a five-month intensive curriculum and that also pose a particular challenge to young francophone learners. The findings clearly showed that non-word repetition accuracy significantly predicted gains in morphosyntactic knowledge at the end of the program and that the prediction remained highly significant even after removing the influence of general intelligence and initial grammar skill. Together, these studies provide strong evidence that PM may be a particularly important factor for the successful development of both vocabulary and grammar skills in an L2 classroom context.

Significant relationships between L2 proficiency and performance on measures of phonological memory in young populations are not consistently found in the L2 literature. For example, Cheung’s 1996 study found a relationship between phonological memory and L2 (English) word acquisition only for adolescent students whose English vocabulary size was below the group median. A favoured interpretation for this finding is that PM may play a more direct role in L2 learning at earlier stages of development when long-term knowledge about the lexical-phonological properties of the L2 is less available to help drive new learning, especially vocabulary learning. Other studies (e.g., French, 2006; French & O’Brien, 2008) have reached a similar conclusion with other groups of children learning English, showing that the involvement of PM in L2 learning declines as a result of increases in L2 proficiency.

Studies have also examined the role of phonological memory in adult L2 acquisition (Papagno, Valentine, & Baddeley, 1991; Papagno & Vallar, 1992, 1995). In particular, Papagno and Vallar (1995) interpreted their findings, in which multilinguals received higher results than monolinguals on a non-word repetition task and in a paired-associate learning test, as indicating that phonological memory plays an important role in foreign language learning. Atkins and Baddeley (1998) used digit-span and letter-span tasks to measure PM in their study of vocabulary learning of English–Finnish word pairs over one week. Their results revealed that span measures were reliable predictors of vocabulary learning success.

Other research with adult L2 learners has shown a direct relationship between PM and speech production. O’Brien and her colleagues (O’Brien et al., 2006, 2007) assessed PM skill (as referenced by serial non-word recognition) and Spanish speech production in groups of [End Page 376] English-speaking adults learning Spanish in a typical foreign language classroom or in the context of study abroad. They found (O’Brien et al., 2006) that PM measured at the beginning of the semester significantly predicted participant improvement on an oral interview at the end of the semester with respect to the correct use of Spanish function words and subordinate clauses. They also reported (O’Brien et al., 2007) that PM explained 4.5% to 9.7% of the variance in actual oral fluency gains as measured by total speech volume and fluidity (speech rate and hesitations/pauses). These findings therefore suggest that PM makes important contributions to L2 oral fluency development, both in terms of the accuracy of utterances and the efficiency with which they are produced in real-time speech.

Some studies (Harrington & Sawyer, 1992; Hummel, 2002; Mizera, 2006) examining adults have failed to find significant correlations between PM tasks (e.g., digit-span, word-span, and non-word repetition) and L2 proficiency. However, it is difficult to determine in some cases whether the reported findings were perhaps influenced by certain methodological factors. For instance, Mizera used non-word repetition tasks designed for children with his adult participants; and Harrington and Sawyer (1992) did not take into account potential native language effects or lexicality effects on span measures. Nevertheless, in a recent study of young adults, Hummel (2009) found that the relationship between PM (as measured by non-word repetition) and L2 proficiency remained significant in non-novice learners but disappeared at the most advanced proficiency stage. This finding provides further empirical evidence that the role of PM in L2 learning appears to decrease as a function of language proficiency level and not necessarily of age.

To summarize, the research carried out in various L2 contexts suggests that tasks that draw on PM are related to children’s overall L2 achievement (Dufva & Voeten, 1999; French, 2006; Service, 1992), vocabulary acquisition in children and adolescents with low to moderate levels of L2 proficiency (Cheung, 1996; French, 2006; Service & Kohonen, 1995) and, in some cases, predict children’s improvement in grammar and vocabulary skills over time (French, 2006; French & O’Brien, 2008). In adult L2 learners, while some research has failed to find significant correlations between PM tasks and L2 proficiency (Harrington & Sawyer, 1992; Hummel, 2002; Mizera, 2006), other research has reported significant relationships between PM and aspects of L2 proficiency in adults beyond an elementary learning stage (e.g., Hummel, 2009). Still other research has reported a specific association between PM and L2 oral production skill in less proficient [End Page 377] adults, and oral gains in function words with more proficient learners (O’Brien et al., 2006, 2007). Given the mounting evidence from various research settings and proficiency groups, PM appears to be an essential memory component throughout much of L2 development.

Phonological memory: Applied aspects

In light of the research pointing out the important role PM appears to play in both L1 and L2 development, an interesting theoretical and practical question arises: Can PM capacity be improved in order to enhance L2 language skills? In the related L1 literature, researchers have explored the role of PM in learners with language- and literacy-related disorders and deficits. Findings from some of these studies have led in turn to research on the possible benefits of intervening with specific training to enhance PM or related processing.

One prominent type of general language learning deficit that has been examined with regard to the role of PM is known as Specific Language Impairment, or SLI. Studies and meta-analyses (e.g., Archibald & Gathercole, 2006; Ellis Weismer et al., 2000; Graf-Estes, Evans, & Else-Quest, 2007; Gray, 2006) have revealed that there appears to be a link between children diagnosed with SLI and PM ability (as referenced by non-word repetition tasks). Children with SLI tend to have large impairments in non-word repetition, with different versions of the task leading to significantly different effect sizes (Graf-Estes et al., 2007). Dyslexia is another language-related disorder, typically characterized by reading and spelling difficulties, which has been found to be related to PM ability (for an in-depth discussion, see Snowling, 2000).

A link between non-word repetition performance and children with L2 learning difficulties has also been found. In one study, Palladino and Cornoldi (2004) examined two groups of children matched for general cognitive skill and found that PM, as measured by two different PM tasks (non-word repetition and forward digit recall), was the strongest variable linked with children identified as having a foreign language learning disability (FLLD) compared to children within normal proficiency ranges based on test scores that included various aspects of English knowledge.

Given the evidence that PM appears to be one important locus of language disorders or deficits, intervention that targets PM improvement might ultimately lead to improved L2 language skills. However, whether individuals can be trained to improve their PM [End Page 378] abilities and, further, whether any improvement would have an impact on L2 learning remains relatively unexamined. Gathercole (2006) cites evidence with twins that heredity but not environment appears to play a role in differentiating non-word repetition performance and suggests this is an indication that training would not have a substantial effect on PM as measured by non-word repetition performance.

Despite the view that phonological memory may be a relatively fixed individual trait, some L1 research has in fact revealed training effects for the overall working memory system, while other studies suggest effects for phonological memory in particular. Studies (Klingberg et al., 2005; Klingberg, Forssberg, & Westerberg, 2002) have indicated a training effect with certain WM tasks in children with ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder), who are thought to have a WM deficit. Furthermore, other studies (Olesen, Westerberg, & Klingberg, 2004; Westerberg & Klingberg, 2007) have reported WM training effects in adults in terms of increased cortical activity. Of note, a recent study (McNab et al., 2009) found that healthy males (aged 20 to 28) were able to increase their working memory capacity following training on WM tasks for 35 minutes a day over a five-week period. This study also found there were changes in brain biochemistry (at the level of dopamine receptors) associated with the WM changes.

Evidence that WM can be trained suggests similar effects may be possible for the PM subsystem of WM. A direct training effect on PM has in fact been reported in an L1 study with children. Maridaki-Kassotaki (2002) found that Greek-speaking children (aged six to nine) who received training on a non-word repetition task (15 minutes a day, four days a week) throughout their first school year outperformed matched children who did not receive such training when later tested on both non-word repetition and L1 reading tasks. This study provides support for the notion that PM capacity can be developed through specific training, with additional beneficial effects on reading skills.

A strong indirect training effect on PM has also been reported in two recent L2 studies. French (2009, March) and French and O’Brien (2008) assessed young French-speaking children on both Arabic and English non-word repetition tasks at the beginning and end of a five-month intensive ESL program. The findings revealed that both repetition tasks were highly correlated, providing almost the same measure of PM throughout the study. However, only performance on English non-word repetition—and not Arabic non-word repetition—increased significantly, suggesting that intensive classroom practice (i.e., training) [End Page 379] of the lexical, phonological, and prosodic structures of English resulted in greater long-term knowledge of these structures, which, in turn, had a significant positive effect on PM performance (as measured by English non-word repetition). Also emerging from this finding is that although basic phonological memory capacity remained unchanged over time (as observed by the lack of significant increases in Arabic non-word repetition skill), the efficiency with which information was processed within this basic capacity did clearly appear to improve (as seen by significant increases in English non-word repetition skill). This suggests that although basic phonological memory capacity may indeed be a fixed trait, the relative processing efficiency underlying this capacity appears sensitive to the effects of training.

Clearly only a few studies to date have examined the direct or indirect effects of PM training on L2 learning. However, taken together, results from the preceding L1 and L2 studies suggest that the feasibility of specific PM training merits further investigation.

The second language classroom

In addition to the suggestion that specific training of PM may ultimately be effective, another way to apply what has been learned about the relation between PM and L2 learning is to adapt current classroom techniques and materials to enable learners to make maximal use of their PM capacity.

In their recent book, Gathercole and Alloway (2008) provide a comprehensive discussion of practical classroom techniques designed to compensate for poor WM, the aspect of memory responsible for activities requiring simultaneous storage and processing. They suggest specific classroom strategies (p. 69), including (a) reducing the amount of material to be remembered; (b) repeating important information; (c) encouraging the use of memory aids; and (d) developing the child’s own strategies to support memory. Many of the activities they present are also relevant as ways to compensate for poor PM, the short-term storage of verbal information, and could be adapted for use in language classrooms.

Second language classrooms have witnessed the rise and fall of numerous teaching methodologies across the years. Particularly prominent throughout a good part of the twentieth century was the audiolingual method (e.g., Fries, 1945), in which it was thought that constant repetition by means of language drills would install good language habits and break old native language habits in students. The [End Page 380] audiolingual method included techniques of drawing students’ attention to patterns in the target language, and specifically highlighted the teaching of phonological, lexical, and grammatical forms and patterns. As will be mentioned later in this section, there may still be a useful role for such procedures in view of maximizing PM resources.

The artificial nature of audiolingual-based exercises divorced from any real communicative practice led to a rejection of this method in its strong form. In the past few decades more ‘communicative’ approaches have come to be widely adopted in classrooms. In these approaches, the objective is to enable the classroom to resemble insofar as possible a naturalistic context in which the target language is used for personal expression of needs, desires, and observations. Communicative approaches tend to emphasize listening to and understanding messages in a primarily oral format. Emphasis is often placed on expressing meaning with little or no explicit focus on formal aspects of language.

It can be argued that PM plays a particularly important role in communicative classroom contexts (as well as immersion contexts), in which learners are required to make sense of large amounts of oral data. Recently, French (2006, 2009) reported that in intensive ESL classrooms adopting a strong version of the communicative approach (i.e., considerable pedagogical emphasis on the conveying and understanding of messages transmitted orally), PM accounted for a large proportion of variation in young adolescents’ listening and speaking skills (72% and 62%, respectively). Interestingly, the variation remained even after removing the confounding effects of general intelligence and prior L2 skill. This suggests, in particular, that learners rely quite heavily on phonological loop processing to develop efficient word recognition and word retrieval skills in contexts consisting primarily of oral input.

Some researchers (e.g., McLaughlin, 1998; Sawyer & Ranta, 2001) have pointed out that the observed relation between working memory and L2 competence may be explained by the fact that a more efficient general working memory allows learners to notice important aspects of the language input by freeing necessary attentional resources that would otherwise be tied up in processing incoming material. Given the findings discussed earlier in this article, we can similarly suggest that the PM component of working memory plays this specific role with regard to processing auditory and acoustic material associated with a given language. The better the ability to rapidly process, retain, and repeat new phonological material, the better equipped the learner is to process the new patterns in a language [End Page 381] being learned. Techniques that ultimately allow individuals to optimize their PM processing speed or overall capacity could be expected to free resources that could then be devoted to processing other aspects of the input, such as syntactic patterns and semantic content. More efficient processing could allow learners to pay closer attention to formal aspects of linguistic input at the same time that they are using the target language to understand and convey messages.

Specific exercises that target increased L2 fluency may be particularly beneficial in compensating for poor PM capacity. Hulstijn (2007) argues that activities leading to increased automaticity of word recognition and retrieval should be given high priority in the classroom. Similarly, Gatbonton and Segalowitz (2005) argue that communicative classrooms need to promote automaticity and fluency by integrating tasks requiring repetition of useful phrases and structures. Although criticized because of their connection to behaviourism, audiolingual-type activities requiring learners to memorize information through rehearsal and repetition may be of benefit for learners with low PM capacity who appear to have difficulty making and retaining accurate phonological representations. The same type of activities may also help to accelerate basic fluency in learners with normal or more efficient PM function. Specifically, within current L2 communicative contexts, teachers might opt for a strategy in which learners are trained to repeat aloud (or subvocally) new lexical items (e.g., single words as well as phrases or chunks) they encounter both inside and outside the classroom. Exercises in the language laboratory may be useful in this regard.

In addition, learners might also be trained via language awareness strategies (e.g., Simard & Wong, 2004) to make phonological, lexical, and semantic associations between their existing lexical knowledge (both L1 and L2) and newly encountered L2 lexical items. Increased reliance on long-term knowledge for learning would therefore help to reduce the processing load on PM, which may be particularly beneficial for learners with less efficient phonological processing skills. Overall, strategies such as these and other activities promoting basic fluency are likely to allow L2 learners to automatize aspects of the target language, thereby leaving additional attentional resources to be directed to other, more complex L2 features.

An ongoing issue taking place against the backdrop of communicative teaching approaches is whether it is desirable, and in what ways, to highlight aspects of linguistic form, as in drawing attention to grammatical structures in the context of meaning-based lessons, as represented by the literature on ‘focus on form’ (e.g., Long, 1991). Although there is [End Page 382] considerable disagreement over the most effective ways to do so, a general consensus in the literature is that some explicit attention should be given to linguistic grammatical forms to allow learners in communicative classrooms to attend to and learn L2 grammatical structures (e.g., Doughty & Williams, 1998; Long, 1991; Norris & Ortega, 2000). The arguments for highlighting formal aspects of meaningful input underscore the value in providing stable, visual support to the L2 in the classroom. Given the constraints associated with the short-term capacity of PM and the advantages of rehearsal and repetition in allowing retention, it can be argued that visual support allows the learner to compensate for limited PM storage capacity and facilitates attention to form. Oral exposure makes it much more difficult for a capacity-limited system like PM to retain information long enough to attend to formal features of the input, including grammatical structures. In a similar view, Randall (2007) argues that because visual or written input is largely permanent, unlike most forms of oral input, it serves to replace the temporary storage function of PM, thereby allowing longer stretches of language to be processed. Individuals whose phonological memory may be less efficient or who appear to be less equipped to handle large amounts of oral input may thus benefit from visual or written aides that put less of a burden on their memory capacity.

A number of studies (e.g., Lund, 1991; Murphy, 1997; Wong, 2001) are consistent with this view, as they indicate that exposure to tasks in the written mode is superior to the aural mode in L2 learning. For instance, Wong found that in L2 tasks requiring attention to form, comprehension was sacrificed when the tasks were presented in an aural mode, while this was not the case in the equivalent written mode. This distinction between allocation of resources between meaning and form in an aural versus written mode is likely to be even more crucial in individuals with low PM capacity.

Some research appears to indicate that individuals with low PM capacity can in fact overcome their limitations when provided with appropriate learning tools. For instance, in a small-scale study with students learning German (N = 13), Chun and Payne (2004) found that students with low PM capacity, as indicated by a non-word repetition task, looked up words three times as often as students with a higher PM capacity. However, when overall comprehension and vocabulary recall scores of low and high PM groups were compared, no significant differences were found. The authors suggest that the learning tool, a multimedia CD-ROM for learning German, which included features for looking up vocabulary and definitions, allowed learners [End Page 383] to compensate for a low PM capacity. Other studies similarly report that more frequent consultation of electronic glosses results in better word acquisition (e.g., Ben Salem, 2007, April). A number of online tools that have been developed to assist learners in retaining L2 vocabulary may be useful in this regard (see, for instance, Horst, Cobb, & Nicolae, 2005).

Further evidence in support of the benefits associated with a written format is found in a L2 study by Payne and Ross (2005), who found that students with lower non-word repetition scores actually had greater L2 output measures (greater number of words per utterance) in text-based computer chatroom discourse than did students with higher non-word repetition scores. The authors suggest that low-span students ‘were taking advantage of the reduced cognitive burden introduced by the chatroom to produce more extensive and elaborate constructions, something they may have found difficult in a [face-to-face] setting’ (p. 15).

Rather than giving priority to communicative activities done in a largely oral–aural mode, a procedure that characterizes implementations of the communicative approach, students could be given substantial visual/written support for language interactions, particularly in beginning phases of learning. Concretely, this could involve having students use and even develop their own written transcripts of communicative activities, such as dialogues, which they are allowed to refer to during classroom activities. Note that Gathercole and Alloway (2008) similarly encourage recourse to visual memory aids as a classroom strategy to compensate for poor working memory. A greater emphasis on written presentation of material in and outside the classroom may ultimately lessen the impact of low PM capacity on L2 learning outcomes.

On a related issue, a number of studies (e.g., Trahey & White, 1993; White, 1998) have specifically looked at whether various input enhancement techniques or input flooding lead to positive effects on L2 performance, without clear long-term positive effects. Still, while input enhancement may not play a significant role in L2 comprehension in a general population, it remains to be seen whether L2 learners with low PM capacity might be particularly susceptible to benefit from such techniques. This question has yet to be investigated.

Other text-based activities, such as reading aloud, might also benefit PM function. Although criticized by communicative language teaching theorists because of its low communicative value in the classroom and also because it is thought to make it more difficult for the reader [End Page 384] to access meaning, reading aloud may ultimately prove to have an important cognitive benefit for language learners: it may activate, via rehearsal, the phonological loop component of WM, which, as discussed previously, is an important mechanism for the automatization of basic fluency skills, particularly vocabulary skill. By having L2 learners read, either out loud or subvocally, one may help these learners to activate their PM through rehearsal and repetition, which in turn may help them to better transfer material to long-term or declarative memory. Consequently, in communicative contexts, regularly using a variety of L2 reading aloud activities (individually or in groups), as well as training students to read aloud on their own both in and out of class, may be beneficial to all learners for improving and/or accelerating L2 fluency skills that depend on PM processing.

Knowledge about the role of PM in L2 learning, while increasing, is still relatively scarce. However, there is mounting evidence that PM plays an important role in early to intermediate stages of L2 learning. In addition, evidence from language-impaired children (e.g., Archibald & Gathercole, 2006; Graf-Estes et al., 2007) reveals connections between PM functioning and language skills. Furthermore, a number of studies with language-impaired children and normal adults report benefits from training on tasks associated with WM (e.g., Klingberg et al., 2005; McNab et al., 2009), suggesting that PM may be similarly trainable. At least one study directly targeting PM (Maridaki-Kassotaki, 2002) indeed reports beneficial training effects in children. More research is needed to verify whether specific training and techniques aimed at enhancing PM capacity and efficiency can be successfully taught to L2 learners. Such techniques might ultimately be useful in improving aspects of L2 learning.

Similarly, more research is needed to determine whether classroom intervention techniques aimed at compensating for a less efficient PM can make a difference in L2 learning. Recourse to fluency-based exercises; strategies aimed at automatizing word recognition and retrieval; ensuring considerable visual/written support for the L2 in the form of written texts, dialogues, and other exercises; regular use of online resources; and occasional strategic use of oral reading are just a few of the pedagogical tools that might lead to enhancing the L2 acquisition process, particularly for learners with a less efficient PM. Of the preceding strategies, providing substantial visual/written support may be particularly effective and relatively easy to add to the typical language classroom.

An important final consideration is that systematic use of various techniques may allow for a more enjoyable L2 learning experience [End Page 385] for learners otherwise hampered by the taxing cognitive demands associated with acquiring the intricacies of a new language.