Judging ShawAn Exhibition

George Bernard Shaw has left a vast legacy of theatrical, fictional, polemical, critical, and philosophical writing. The first person to win both a Nobel Prize and an Academy Award, Shaw bridges the Victorian era and the contemporary culture of celebrity. The GBS brand came to be recognized globally as referring to an Irish provocateur with a red beard and startling opinions. He was a master of self-invention, a nobody who captured the zeitgeist and one of the first private individuals to understand fully how to generate—and how to use—global fame. The Royal Irish Academy and the National University of Ireland, Galway created a companion exhibition to the publication Judging Shaw by Fintan O'Toole (Royal Irish Academy, 2017). We reproduce the content of the exhibition for readers of SHAW, but the exhibition must be seen in person to appreciate the design and full impact. The touring exhibition is available for loan.

exhibition, Bernard Shaw, biography, Judging Shaw

George Bernard Shaw has left a vast legacy of theatrical, fictional, polemical, critical, and philosophical writing. The first person to win both a Nobel Prize and an Academy Award, Shaw bridges the Victorian era and the contemporary culture of celebrity. The GBS brand came to be recognized globally as referring to an Irish provocateur with a red beard and startling opinions. He was a master of self-invention, a nobody who captured the zeitgeist and one of the first private individuals to understand fully how to generate—and how to use—global fame. [End Page 305]

After a drawing of Shaw by Alexander ('Alick') Penrose Forbes Ritchie for a cigarette card, 1926. Created by Fidelma Slatter, graphic designer at the Royal Irish Academy. Rermission granted by Royal Irish Academy.

The Invention of GBS

Shaw's immense fame was entirely deliberate. It is one of the great achievements in the history of advertising. The GBS brand would project an image of almost effortless brilliance, claiming to be the product merely of "the accident of a lucrative talent." But accident had very little to do with it. With nothing but his own resources of energy, mind, and personality, Shaw forged an identity that was at once dazzlingly complex and easily recognizable, supple enough to be reliably unpredictable but fixed enough to be instantly familiar. It was a unique form of celebrity: a vast popularity that [End Page 306] depended on a reputation for insisting on unpopular ideas and causes, a reputation for pleasing the public by provoking it.

His propagation of an image was inextricable from his theater—GBS was Shaw's greatest character. He never affected the pose of careless creator, quietly indifferent to his creation. Instead, he paraded himself as a flagrant propagandist with serious designs on his audiences, on society, on history.

Photo of Shaw by Sir Emery Walker, July 1891, © national Portrait Gallery, London.

[End Page 307]

The Making of GBS

Born George Bernard in 1856, the son of George Carr Shaw and Lucinda "Bessie" Gurly, the young "Sonny" eventually coined a term for his father: "I was a downstart and the son of a downstart." He grew up in that rich seedbed

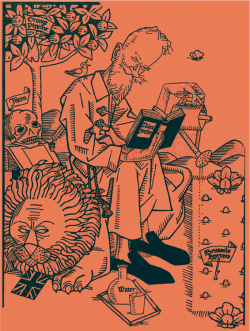

Etching by Edmund Dulac, 1928, featuring Shaw seated on the British lion, reading nietzche and watering a patch of Brussels sprouts. Private collection. Permission granted by helena King.

[End Page 308]

of literary talent—a family coming down in the world; where their ancestors had been high-ranking and successful, Shaw's grandfather had lost the family fortune and left the Shaws at quite a different level in society. Shaw did not love his father and in later life recalled being "disabled" with laughter as a boy at the sight of his drunken father coming home, presumably at Christmas: "An imperfectly wrapped-up goose under one arm and a ham in the same condition under the other butting at the garden wall in the belief that he was pushing open the gate and transforming his tall hat to a concertina in the process. … If you cannot get rid of the family skeleton, you may as well make it dance."

Shaw's house was full of music. His mother Bessie, a fine mezzo-soprano, and his sister Lucy became pupils of a local music teacher, George Vandeleur Lee, with whom they left Ireland for London in 1873, leaving Shaw behind with his father. Shaw gained employment as a junior clerk in a land agent's office and was successful in the role. But it was not, of course, what he wanted: "I hated my position and my work." While the young Shaw, a voracious reader, was migrating long before he left Ireland, his physical departure from Dublin to London came in April 1876, three months before his twentieth birthday.

GBS versus England

Learning to "make an appearance" was a key part of Shaw's development. The Shaw who arrived in London in 1876 to live with his mother and sister Lucy was not such a pretty picture. He would live with them until he was twenty-nine, dependent on a small allowance of a pound a week. In his first nine years as a writer, he later recalled, he made a total of six pounds, of which five was for a "medical essay" written for a lawyer. He was moreover intensely aware of his foreignness.

The combative nature of his music and drama criticism and commentary was the beginning of GBS's solution to the problem of Irish exile: patronizing the English. As a mere gauche young man, he was trying to learn how to ape Englishness. But as the emergent GBS, he tapped into a new cultural force—reverse snobbery: "The alleged aptitude of the English for self-government … is contradicted by every chapter of their history."

This is what the GBS persona specialized in: berating the English for their dull brains. But perhaps Shaw's greatest insight was that the best way to be Irish in England was to be German. While GBS the socialist agitator was an established figure in the England of the 1890s, GBS the playwright arrived in London via Germany. Although relatively unknown in England, Shaw's German-translated plays were touring the world and making GBS a global brand. By the time Pygmalion, for example, opened in London, it had already played not only in Berlin and Vienna, but in Budapest, Warsaw, Stockholm, and, remarkably, in New York City's German-language diaspora theater. [End Page 309]

GBS versus Ireland

In the summer of 1916, Shaw drafted what might have been his most important play: a dramatic monologue written for the voice of a very specific actor. It was to be performed for a very small and select audience, and it had a very precise purpose: to save a life. The actor Shaw envisaged for the part was Roger Casement, who was about to go on trial for the capital crime of high treason for trying to import arms from Germany to Ireland as part of the Easter Rising. Shaw's "national dramatic event" was not staged; Casement and his legal team instead put up a more conventional defense, with the inevitable result of Casement's execution.

Shaw did not directly approve of the 1916 Rising. He opposed Casement's alliance with Germany, but he never deviated from a passionate insistence that Ireland was and must be its own country and that British rule was an illegitimate imposition. He insisted that aggressive Irish nationalism was a fever that could be cured only by freedom. What makes him important as a thinker about Ireland, though, is that he also insisted on something else: that national independence was not an end but a beginning.

Shaw's relationship to Irish nationalism was complex. He had no truck with notions of identity based on ideas of ethnic distinctiveness; he knew well that Irish identity was not confined to the island but existed also in

Photograph of Shaw on Burrin Pier, Co. Clare, 1915. The pier is the setting for the fourth part of Back to Methuselah. Courtesy of the University of Guelph.

[End Page 310]

a vast diaspora; and he persisted in asking an awkward question—what happens after the revolution? When the Republic of Ireland was officially inaugurated at Easter 1949, The Irish Times asked GBS to comment on whether it was a step forward or backward for Ireland's development. He replied, "Ask me five years hence. If our terrible vital statistics improve to a civilized level then our steps will have been

Cyril Cusack starring as Captain Bluntschli in the 1937 production of Arms and the man at the Abbey Theatre, Dublin. © Abbey Theatre Digital Archive, NUI Galway.

[End Page 311]

Shaw's Theater

GBS had no success as a playwright in England until 1904, though he was by then already a major figure on the German stage. Plays like Man and Superman, Major Barbara, and Pygmalion differed radically from what audiences were used to. These plays did not have single star roles, but called for the new repertory style of ensemble acting. They used comedy to deal with very serious subjects, from poverty to sexual oppression. They pushed Oscar Wilde's paradoxical methods to ever more unsettling extremes. They subverted conventional morality and played dizzying games with traditional forms. They combined laughter with polemic, entertainment with didactic purpose. And they left audiences with deliberate anticlimaxes, forcing them to think for themselves about what the afterlives of the characters might be. After Henrik Ibsen, Shaw did most to restore the stage as an arena in which society's dramas could be played out.

It is easy to see Shaw as a writer who brings the concerns of the wider world into the theater. But in a sense, his real achievement was the opposite: he took the concerns of the world and treated them as if they were theater. His great gesture was to treat economics, power, gender, religion, social class,

Photograph of Shaw and the Fabian Society member Margaret McMillan with pupils of Deptford Baby School, London c. 1928. Courtesy of the London School of Economics.

[End Page 312]

nationality, and war as if they were on stage. For on the stage—at least when theater is good—nothing can be taken as a given and every idea and character must earn its keep. Everything in the theater is flux, conflict, contradiction. Shaw tried to show that this is exactly so for political, moral, and social ideas as well. He politicized the theater but he also dramatized public discourse.

GBS's War on Poverty

As a child, Shaw was regularly brought for walks by a female servant, who would take the opportunity to visit her friends in the city's notorious tenements. Many years later Shaw could still vividly evoke "the young women with the waxen faces, the pink lips, the shuffling, weary, almost ataxic step, representing Dublin's appalling burden of consumption."

Until at least the 1960s, Shaw was by far the most widely read socialist thinker in the English language. And at the heart of this thought was that visceral hatred of poverty he breathed in with the fetid air of the Dublin slums in the days of his youth.

GBS demolished the claim that wealth is deserved because it is the result of hard work. Idleness, he pointed out, was hardly confined to the shiftless poor—it was a way of life for "these well groomed monocular Algys and Bobbies, these cricketers to whom age brings golf instead of wisdom." He challenged the perception of poverty as a product of personal failure or mere bad luck, or as a necessary and inevitable corollary of economic progress. For Shaw, poverty is not the cause of crime—it is the crime.

Shaw anticipated an idea that has acquired new impetus in the twenty-first century: basic income. His practical suggestion in the preface to Major Barbara is for a "universal pension for life," essentially a more radical version of the old-age pension that was coming into being in the most advanced industrial societies. In effect, this does not in fact mean that everyone has the same income, merely that each citizen has enough for a free and dignified life.

The Death of GBS

On 14 November 1914, when war hysteria was still at its height, the New Statesman published a special supplement titled "Common Sense about the War," in which Shaw ferociously attacked the official justifications for the fighting. It is by far the bravest thing Shaw ever did.

Yet "Common Sense" is not actually an argument for Britain to pull out of the war. Shaw believed that Britain, instead of being engaged in a crusade [End Page 313] to save civilization, "was fighting for its life to escape the ruin its militarist governing class had brought upon it." In "Common Sense" he insisted that the war must lead to the end of secret diplomacy, full civil rights for all citizens, public ownership of large parts of the economy, and a "genuine

Cartoon drawing by Powys Evans of Shaw impaling himself with a quill pen. © Getty and the estate of Powys Evans, and reproduced by permission of Terence Taylour.

[End Page 314]

working-class democracy." He also argued—with great prescience—that when Germany is defeated, it must not be punished.

This argument finished GBS. He was no longer seen as properly devoted to English interests. Libraries and shops withdrew his books from circulation; newspapers urged readers to boycott his plays. He was effectively expelled from the Dramatists' Club and forced out of his position on committees of the Society of Authors. Part of the shock of "Common Sense" was the discovery that he was entirely serious.

Yet from being a social and artistic pariah, Shaw gradually came to seem like a sage. His outrageous criticisms chimed with a growing mood of disillusionment. As relentless war ground millions of lives under its wheels, Shaw's dissenting spirit was no longer quite so treasonable. He was even invited to visit the front in France and Flanders by the British commander-in-chief Douglas Haig. Shaw accepted, and the invitation marked at least a truce in the war on GBS. Just over a decade after the end of the war, Shaw would be offered a knighthood—which of course he had the pleasure of refusing.

The Dark Side of GBS

While Shaw was inaccurately accused of promoting eugenics, a precursor to the mass exterminations of the 1930s and 1940s, this serves largely to distract from his real failure. It's not that he prefigured the use of political mass murder in the twentieth century—Shaw failed to see the true nature of fascism, Nazism, and Stalinism.

In his old age, the great skeptic allowed himself to believe just what he wanted to believe—that the totalitarian regimes of Mussolini, Hitler, and Stalin were rough harbingers of real progress and true democracy. GBS was by no means the only artist or intellectual to be deluded by the promises of regimes that "got things done" while democracies struggled to end the Great Depression. But no other artist or intellectual had his standing as a global sage. His sagacity proved to be useless when it mattered most.

Shaw's early reaction to Hitler's coming to power showed a hopeless inability to understand what Nazism was about. He strongly denounced Hitler's anti-Semitism yet described his proclamation of compulsory labor as "pure Bernard Shawism." Shaw himself never removed his plays from performance in Nazi Germany, asking rhetorically, "Why shouldn't they be played before cannibals?"

Equally, Shaw did not object when his good friend and German translator Siegfried Trebitsch's name was removed from theater programs for [End Page 315] productions in Germany—purely, of course, because Trebitsch was of Jewish descent. When Trebitsch complained of it in 1936, Shaw dismissed it as "a tiny drop in the ocean of persecution." This was entirely accurate, but it was also a neat evasion of the idea that Shaw himself might have any responsibility to take a stand.

head and shoulder portrait of Shaw, c. 1920. Courtesy of the London School of Economics.

[End Page 316]

Judging GBS

When George Bernard Shaw died in 1950, Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of independent India, said, "He was not only one of the greatest figures of his age, but one who influenced the thought of vast numbers of human beings during two generations." The claim may seem surprising: few intellectuals (and certainly no politicians) would today identify themselves as Shavians. If Shaw really influenced the thought of vast numbers of people over two generations, would we not expect to find him still

Photograph of Shaw posing in the doorway to his writing hut at Shaw's Corner, c. 1929. Courtesy of the London School of Economics.

[End Page 317]

ensconced among the titans of intellectual modernity, along with Freud, Marx, and Einstein? The answer may be that Shaw's achievement was not so much to teach people what to think but to teach them how to think. He democratized skepticism and encouraged ordinary people to question all received ideas.

Shaw's status as an artist seems more secure now than might have been predicted even a few decades ago. He is one of a mere handful of dramatists in the English language with half a dozen plays that seem likely to hold the

Poster, John Bull's Other Island, Lyric Theatre, 1971. © Abbey Theatre Digital Archive, NUI Galway.

[End Page 318]

stage for the foreseeable future—more than any of his great Irish predecessors Oliver Goldsmith, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, and Oscar Wilde.

As a thinker, Shaw had an unmatched ability to engage not just the highly educated elites, but the first generations of mass readers, the millions who devoured newspapers and haunted public libraries, who joined trade unions and feminist organizations, social clubs and socialist societies, who hungered for ideas about the world. He was the touchstone of the autodidact. The history of the cheap paperback book is intertwined with the history of GBS. And not for nothing—they both belonged in the hands of working men and women.

Shaw's Plays on Later Irish Stages

Audiences would seldom be without the opportunity of seeing the plays of GBS beyond his lifetime. The ability of GBS's work to adapt and speak to the globalizing and modernizing world of the 1960s and succeeding decades allowed new companies and theaters to reinvigorate Shavian theater in terms of practice and production.

The initials and enduring brand of GBS were pictured on the program cover of a "Festival of Anglo-Irish Theatre" by Druid Theatre Company in 1977. Druid cofounder Garry Hynes also directed A Village Wooing and The Fascinating Foundling in 1978 and 1979. In Belfast, Cork-born director Mary O'Malley staged Shaw's satire on "the Irish Question," John Bull's Other Island, in August 1971—the same week that the British Army initiated Operation Demetrius, which enforced "internment without trial." While Anglo-Irish relations fell to a perilous low, audiences and critics signaled their emphatic approval of John Bull's Other Island, commenting the play has "blown the cobwebs off Shaw."

Siobhán McKenna, the celebrated actor who was dubbed by Brian Friel as "the idea of Ireland," adapted and starred in Shaw's play Saint Joan. McKenna translated the script into Irish for a production at Taibhdhearc na Gaillimhe in 1951, and later starred as Joan to critical acclaim on Broadway in 1956. Saint Joan found new international acclaim after the Second World War by reinstating Shaw's original message of change and hope in the face of despair.

The Legacy of Shaw

Shaw, who was a pioneer photographer, took great care to experiment with capturing his own image. Varying light, space, location, and angle, these [End Page 319]

Cartoon image of Shaw emerging from a pile of laurel and maple leaves, with a wreath of leaves on his head, undated. Courtesy of New York Public Library.

photographs of Shaw have become an archive of the aging image and body of GBS, a figure as recognizable as his own initials.

Shaw himself had complex opinions about his effigy and legacy. He discarded his birthday by deed poll and famously never celebrated his birth, telling a reporter in Scotland on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday that he was "not young enough to be really proud of my age and not old enough [End Page 320] to have become really popular in England." Shaw disagreed with plans to mount a commemorative plaque on the house of his birth on Synge Street, Dublin, saying he would strictly consent only to the detail he submitted and that the plaque "must bear no inscription of opinion as to my merits

Judging Shaw by Fintan O'Toole book cover (Royal Irish Academy, 2017).

[End Page 321]

and demerits and must state only the unquestionable fact that I once lived in this house."

Considering his own mortality, Shaw later joked that his ghost would be "enormously amused" if his statue, cast in bronze by the sculptor Paolo Troubetzkoy, would be placed on College Green in Dublin, next to the statues of Oliver Goldsmith and Henry Grattan, figures who were both Trinity College alumni and symbolic of the formal classical education Shaw himself did not receive. Charlotte Shaw took great efforts to ensure that Dublin would "possess a good portrait" of her husband, donating one by John Collier to the National Gallery during GBS's lifetime.

Geneses and Acknowledgments

The Royal Irish Academy and the National University of Ireland, Galway created a companion exhibition to the publication Judging Shaw (Royal Irish Academy, 2017). We reproduce the content of the exhibition for readers of SHAW, but the exhibition must be seen in person to appreciate the design and full impact. The touring exhibition is available for loan, and inquiries can be sent to publications@ria.ie.

The exhibition was co-curated by Ruth Hegarty, Barry Houlihan, Fintan O'Toole, and Jeff Wilson and designed by Fidelma Slattery. Simon O'Connor generously gave material from the Judging Shaw exhibition at the Little Museum of Dublin. [End Page 322]

ruth hegarty is managing editor of the Royal Irish Academy and lives in Dublin in Ireland.

fintan o'toole is a columnist with The Irish Times, Leonard L. Milberg Visiting Lecturer in Irish Letters at Princeton, and a member of the Royal Irish Academy. His books include Judging Shaw, Heroic Failure: Brexit and the Politics of Pain, and A Traitor's Kiss: The Life of Richard Brinsley Sheridan.

barry houlihan is an archivist at National University of Ireland, Galway. He teaches theater history and archives and digital cultures.