Master-Slave Sex Acts:Mandingo and the Race/ Sex Paradox

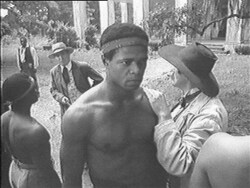

Slaves subjected to evaluation by slave buyers in Mandingo. Video frame enlargement.

[End Page 42]

Not quite blaxploitation and not quite plantation-genre film, Dino De Laurentis' Mandingo (1975) portrays the private sex act between masters and slaves as an intense paradoxical site of sexual pleasure and racial domination. Against a Hollywood history of representing rape and sexual assault of innocent white women by menacing black men such as in D.W. Griffith's Birth of A Nation (1915), Mandingo posits sex acts as the primary constitutive technology of racial domination in U.S. slavery while raising the possibility of mutuality, recognition, and affection between masters and slaves. The film's polemic proposal evades more serious engagement when most frequently described as a "trashy southern gothic that uses interracial sex as its steamy selling point"1 or as "a sadomasochistic Old South wonder"2 that capitalized on sex for box office profit.3 Prematurely, the film is dismissed as a pastorally racist project, that is, a telling of slavery from the point of view of slave sexual contentment. In this article, I explore how paying attention to sexual relations and the explicit sex act acknowledges the paradox of pleasure and violence in racial subjection.

Critics who prioritize race as the main analytic lens for understanding Mandingo celebrate its masculinist militant politics,4 or privilege revolution as the solution to slavery as an institution of absolute domination.5 Both moralistic dismissal and uncritical celebration of the film avoid how sex and sexuality function [End Page 43] in the cinematic oeuvre of racial representation. The film's hypersexual representations of plantation era masters and slaves who desire each other exhibit a complex construction of racialized sexuality, i.e., how sexuality complicates how we understand racial subjection. That is, sexual practices, identities, and acts centrally constitute racial formation. In Mandingo, what occurs when the racial order is challenged at the site of the sex act is a confrontation of the para- dox of slavery, an antagonism between freedom and domination as defined by the Hegelian dialectic. I am interested in formulating an understanding of the relationship between sexual subjugation and racial subjectivity through a consideration of explicit sex acts between masters and slaves in 1970's representations of the plantation-era as both disciplining subjugation and liberatory self-formation for racial subjects. The moment of the sex act is not only a site of domination, but of self and subject formation as well.

To pay attention to the meanings of sexuality as such, is to confront the general tendency to fear and flee from complications netted by illicit sexuality that continues in racial discourses of representation today. Rather than flee from sex or ignore race, the racialized sex act is a scene where seemingly coherent racial identities fracture and transform in the realms of the intimate and in the larger world of racial slavery. To study sex acts within the context of everyday sustained brutality does not simply perpetuate enforced sexualized subjectivities for racial others, but actually acknowledges the specter of violence haunting racial and sexual relations and self-formations, especially when desires transgress normative bounds.

Sexual Practices and Racial Identities In Slavery

Breeding slaves, but not selling crops, the plantation of Mandingo is set in the American South at the turbulent dawn of abolition, where an aging slave master prepares his only son to take over the family plantation. The old master Maxwell instructs young Hammond to "purchase" a wife so as to sire an heir. For the purposes of breeding chattel, he must also buy a""Mandingo" buck, a male slave. In the film, a "Mandingo" represents the finest stock of slaves deemed most suitable for fighting and breeding. When Hammond realizes his [End Page 44] new wife Blanche is not sexually pure, he purchases a virgin slave woman Ellen to be his "bed wench." In revenge, Blanche beats Ellen so she miscarries the master's child. Blanche also lures the Mede the Mandingo into a sexual relationship that produces a mixed race child. As a consequence, the furious master orders the death of the child and Blanche, casts off Ellen, shoots Mede into a boiling cauldron, and then stabs into him with a pitchfork. The violence leads to a slave rebellion culminating in old Master Maxwell's death and Hammond more deeply bound to mastery, as dehumanizing to white men.

Mandingo interrogates the meaning of sexual pleasure within the enforcement of racial identities in slavery. The film shows how it is precisely sex that organizes racialized slaves and masters in a system of subordination through the routine discipline of bodies, the medical classification of superiority and inferiority, legal sexual defilement and forced consent, and the steely control of emotions and feelings in sexual transaction. The master ascertains power through his use and enjoyment of enslaved black men and women and constrained white women. Mastery in Mandingo includes the initiation of slave women into sexual life. The master enjoys many black women's bodies to fulfill his own sexual lust, while producing chattel for the security of his income. He derives pleasure as he simultaneously applies his power. A slave woman either serves as his "bed wench" in demonstrating desire for and providing him sex, or she acts as his sow, breeding with bucks for the master's ultimate profit. Similarly, the "fighting slave" buck pleases the master who gains virile pleasure through the slave's body as surrogate for his manhood in the exciting and heated public arena of boxing. The master also profits from mating the black male buck with wenches, regardless of incest, so as to populate his chattel. Furthermore, the master ignores his wife into a depraved position by limiting her white woman's sexuality for pleasure. He engages her primarily for procreative purposes. Operating under the binary logic of Madonna-whore, he performs well with black women in a way very different from his wife. Hers being the only "human" blood that qualifies for the reproductive purposes of siring racially legitimate heirs, she is disallowed any sexuality for pleasure. Blanche, however, enters the scene as a sexually experienced woman who, as a mistress, finds no sexual agency within the system of slavery. [End Page 45]

Sexual pleasure intertwines with violent punishment to maintain the racial order within the film. When Hammond's wife discovers his favored wench pregnant, she beats her frantically, kills the child, and calls her a "dirty fornicating animal." To train for the fight, Mede is bathed in a boiling cauldron of water over a fierce fire so as "to toughen his hide." When beating slaves, the masters describe how "niggers" do not feel the same pain as white men. Mastery is ensured through the control of others who exist for the white patriarchal master in explicit bodily terms. Through continual sexual and physical subjection of others, masters confirm their superiority. Masters continually work to instill fear so that slaves sacrifice their bodies to power.

At every crucial filmic instance, however, slaves resist the masters' violent construction of their bodies, psyches, and self-consciousness. And the editing, shot compositions, performance, and character construction privilege slaves' resistance to the masters' actions. Displayed in the public sphere of the auction block, they are priced and sold depending on the qualities of their bodies. Slave buyers fondle the chattel to emphasize their primacy as sexualized bodies. In the opening scene, the houseslave Mem leads a long procession of slaves for evaluation by the slave trader. Shots of the enraged rebel Cicero interrupt the ease of the transaction. He must spread his legs and bend over for the examination of the anus. Like a dog, he must fetch sticks thrown by the trader, but defiantly throws it back upon his return. The slaves open their mouths for the intrusion of the slave trader's fingers as cigar smoke is blown into their mouths. Their steely looks and subsequent attempts to escape contradict the passivity of the scene. A German widow explores Mede's crotch on the auction block as he holds himself taut against the invasion. Here then, masters certainly discipline slave bodies by requiring their non-stop everyday violation by known and unknown hands. Slaves are seen as accustomed to such violence upon their bodies, which range from everyday unwelcome groping to sexual assault by virtual strangers. Sexual subjection disciplines the body so as to maintain and reproduce slavery in the everyday— in ways that are also met with resistances that create ambiguity within the relations of power.

While the master inflicts domination repeatedly in public and private, slaves do not passively accept the violence continuously. Within a home life where [End Page 46]

The young wench beaten by her master. Video frame enlargement.

her body is sanctioned for rape, a very young wench demonstrates that she understands her lot. Her master hands her off, gives her like a pillow to Hammond's cousin, who happily claims his entitlement to violate her. Despite her seeming passivity to the ritual sexual assault, the scene is shot to prioritize the violence of the experience. Her eyes widen to the agony of his spanking. No matter how accustomed she may be, the pain continues to be shocking. While she may seem to accept her slavery, her facial expressions and bodily convulsions show the forcible violence and demeaning subjugation meant in these acts. The master demands her complicity in order to secure his pleasure in the need for her to say she likes it. Within this moment, she defends herself by making any semblance of her self and her experience unavailable to him. He shoves her to the bed, turns her over on her stomach, undoes his belt and whips her fiercely for her refusal. By assaulting her body, he forces her into a conscious acknowledgment of his mastery. She registers total contradiction through bodily, and not so much verbal, speech. The shot shows the drama of the wench's rape: a close-up of her pain in the foreground, and looming behind [End Page 47] her in fuller body shot, the white man with the power of his whip. Unseen by the master, the viewers see her facial expression of physical and psychic torment. The film aligns itself to her by focusing on her pain. She avoids expressing her pain to resist how the master appropriates it for erotic purposes as well as to affirm his power.

Within this particular system of domination, the slave experience of sexual acts seems to undermine what may be immovable roles of slavery and mastery. The representation of pain and coercion dispels the pastoral mythologies of naturalized hypersexual qualities or propensities while also providing what Elaine Scarry calls the "insignia of the regime."6 Within the film's symbolic representation, masters learn their superior position by taking up sexual entitlements just as slaves recognize their role within the system as forcibly prone to their masters. Sexuality is the site of domination in slavery. And within such experiences, the film represents slaves and masters forming selves that cannot be articulated outside of sexual subjection. The film makes the argument for sexuality as a system of parts for the institution and disruption of slavery. How do we understand the potential of these sexual relations between masters and slaves?

Sex, Race, and the Master and Slave Dialectic

Mandingo presents certain sex acts as cracks within the slave system's house of terror. I now read the main sex scenes between two pairs of masters and slaves closely so as to show how they define sex—in both the infliction and subordination of racial slavery—as the form of agency in Mandingo. Within the film, sexual subjection of slaves by masters provides the key to its dissolution, but is precisely the mechanism that keeps slavery in operation. Mandingo aims to destabilize the claim that all master-slave sexual relations are always already scenarios of absolute domination that render slaves as property for the pleasure of the master. Through a sexual form of racial subjection, it posits a dialectical relationship between slavery and mastery.

A romanticized relationship transpires in the sexual relationship between the white master Hammond and his black "bed wench" Ellen. Tenderness [End Page 48] constructed between master and the wench attempts to disrupt their locations in order to transform each of them into troubled new identities. The master's own uncharacteristic practice of feeling for his bed wench Ellen, and her status as his "surrogate wife," disturb the permitted laws of recognition within the filmic world but also confronts the audience by rewriting the terms of interracial pairing through sexual and looking relations.

Organized as new looking relations within slavery, the love scenes between Hammond and Ellen are constructed as desirable and progressive. Immediately after the whipping scene, the bewildered Hammond sits in bed while Ellen fearfully steals shy looks at him from the doorway of the bedroom next door. bell hooks asserts that "there is power in looking"7 when describing it as a means for securing the master's dominant position within slavery, for "The politics of slavery, of racialized power relations, were such that slaves were denied their right to gaze."8 The master's gaze functions as a panopticon in the Foucauldian sense wherein the master's surveillance disciplines slaves by "turning in on themselves" in a form of self-policing.9 bell hooks points to how slaves did indeed look back at masters, albeit in secret so as to secure power in not looking. Slaves who choose not to look back strategize relations of self-protection by making unavailable their true feelings to the master and his gaze. Hammond demands Ellen to explain her acts of "looking back" so he may uncover what she really thinks. Timidly, she expresses her surprise at his "care for what was being done to a wench by a white man." The conversation is framed as liminal, or a passing moment where master and slaves meet as lovers.

The film also eroticizes the mastery of the white mistress and the slavery of the black male slave. Mastery is contradictory for white women in slavery because they undergo injury in white patriarchy as they benefit from white supremacy. Blanche flees from her own childhood household where she must remain silent about incest. Marriage, as her only way out of the confines of family in that historical moment—relies on her sexual purity. On their wedding night, Hammond discovers how she disqualifies from good white womanhood. Throughout the film, he punishes her by refusing her sexual pleasure. Her desperate whispers of "I craves you" worsen her predicament. The husband pathologizes her sexuality when saying "You strange for a white lady." [End Page 49] In a notable contrast, the black wench Ellen is constructed as the proper woman and the mistress lewd and lascivious.

Within the sexual economy of slavery, white women are incompatible with any sexuality apart from reproduction. While sexuality is a site for her subjection, she defines her own mastery by her bodily subjection of slaves, including Mede. Increasingly drunk, the mistress commands Mede to please her sexually. She threatens him with death if he will not sexually fulfill her. In effect, she rapes him through the threat of falsifying a rape by him. She exerts the protection reserved for her racialized femininity as his endangerment. She tells him the master will listen to his wife and not a "nigger." He surrenders to the force of her threat and also fulfills his desire. However, he is bound to perform the sexual act for if he flees, her word will condemn him to death.

Yet the mistress-Mandingo sex act is constructed as a different form of meeting from rape; it is meant to arouse the possibility of racial freedom through sex between a diminutive Susan George and the bigger bodied, recognizably famous boxer Ken Norton. The scene of their bodily contrast—big and small, black and white—is the stage for Blanche to expose the pain of her bodily subjection within slavery. Denied sex by the master and driven into a realm of asexuality, she imposes her need for recognition onto the slave Mede. She trespasses against the rules preventing her from desire. In the darkness of her room, she touches him very gently and very slowly strips his clothes in silence. Mede looks down on her as she strips him. As she strips herself, she supposedly strips off her mastery. An extreme close-up shot of her face reveals a very emotionally ripped expression as she rubs her cheeks against his chest. In an unspoken declaration of the need for a meeting of their personhoods, she frames his face with her hands and they look at each other, directly in a way that is constructed as "new." Like the looking relations between Hammond and Ellen, this meeting is also framed as transformative of slave relations. The characters' looks of intensity communicate the weight of the sexual act as a kind of threshold moment in the film, one with supposedly enough conscious and transgressive power to undo the racial order.

The Mandingo-mistress and master-wench sex acts presumably defy slave relations. Fulfilling self-invested sexual feelings for each other outside the [End Page 50] white male master's grasp, the encounter between Blanche and Mede threatens slavery with new identities produced by corporal liaisons. Hammond and Ellen present a seemingly rupturous new order in slavery through "love." Do these scenes of sexual love between masters and slaves lead to freedom from—or do they deepen— the institution of slavery?

Hegel, Sex, and Race: Mutual Recognition

Different generations of thinkers on race—from W.E.B. Du Bois, to Frantz Fanon, Orlando Patterson, and Paul Gilroy—have appropriated Hegel's dialectic for understanding master-slave relations.10 I bring together high (master, established, or canonical) and low (contemporary film, race, and sex) discourses to articulate how Mandingo enables a rethinking and rewriting of Hegel's dialectic in ways relevant to our understanding of race, sexuality and representation. Through a rewriting of the Hegelian master-slave dialectic, the film constructs a momentary breakdown of the slave system through outlaw sex acts meant to question absolute domination in slavery. Sex acts supposedly trespass the most intimate laws of the racial order when the master affirms the humanity of the wench and the rape is rewritten by desire and recognition in the encounter between the black man and white woman. By the end of the film, for example, Mede even expresses surprise at the master's rage upon him when Blanche births a black baby.

The Hegelian notion of mutual recognition describes the process wherein the lord depends on slaves (and their work) for the acknowledgement of his (sic) mastery or self-certainty. The lord is the independent master who exists in and for himself, while the slave is dependent upon and works for another. The slave affirms the master and is in turn subjected into a position of servitude. He sacrifices his self-certainty in service of another. Through Mandingo, I propose a new appropriation of the Hegelian lord and bondsman relation within the possibility of mutual recognition occurring during outlaw sex acts perpetrating as social progress. Mutual recognition occurs in the self-conscious representation of sex as taboo within a system where recognition must discipline rather than transform subjects. [End Page 51]

In Mandingo, mutual recognition occurs when shared displacements are recognized through sexual meetings disallowed in slavery. In these sensuous moments, Mandingo frames slaves and masters as agents who have potential to re-frame, but not radically turn over, subjected roles in slavery. The film argues that both masters and slaves reconfigure themselves against the brutalities of the system when a different form of recognition occurs between them through sex. Mutual recognition proposes that outlaw sex acts introduce liberatory potential born out of enslavement. This proposal questions the implications of sexuality, perhaps now read as a mechanism that not only forms subjects but un- binds them out of and within slavery. Setting up masters and slaves in tender and/ or ecstatic meetings across unequal power locations, the film uses sex to frame slaves' access to freedom and to certify their humanity. The slaves in Mandingo are the ones with the potential for redemption as revealed in the encounter of bodies, psyches, and self-consciousness during sexual engagement. This is the master-slave impasse upon which Hegel builds his idea of the dialectic.

Hegel formulates that the slave does have a self-consciousness but one that is checked by the master. Describing an original and ahistorical struggle between master-slave, the master secures his position of domination by "risking his life," while the slave "who has not risked his life may well be recognized as a person, but he has not attained the truth of this recognition as an independent self-consciousness."11 In his original life-or-death struggle wherein two self-consciousnesses struggled over the other, the master wins and subsequently dominates the slave. In the master-slave dialectic, however, the slave's self-consciousness is still the one with potentiality for transformation; in other words, the one in the process of becoming. The master is already free. Yet his freedom is contingent on the slave's bondage. Not free within the world of slavery, the slave holds the potential for revolt that can become a pursuit of freedom. In Mandingo, the sex act is constructed as the new life-or-death struggle between master and slave. The slaves "agree" to sex in fear of death. The slave performs labor in fear of the master's capacity to kill him.12 Within the film, sex is the work the slave performs in fear of his own death.

This fear of death is precisely what enables the slave towards a new self-recognition, in an analogy of sex and work afforded by the film. Through this "fear, [End Page 52] the being-for-self is present in the bondsman himself; in fashioning the thing, he becomes aware that being-for-self belongs to him, that he himself exists essentially and actually in his own right...."13 The slave realizes desires belonging to the self in ways that produce new identities that threaten the structures of slavery. Through the independence of the sex act, slaves come to recognize their own self-consciousness as apart from the master. The process of sexual work transforms them into recognition of their own self-certainty. They realize that the master usurps the work they perform in the bondage of terror and fear. In Mandingo, the slave consciousness is not fixed. Unlike the master who works to maintain his power at all costs, the slave can potentially transform, become, and progress out of his hold. Since the system disallows self-consciousness for slaves, the recognition of independent desires for the enslaved through sex could potentially bring an autonomous sense of self. In effect, feelings and emotions can emerge in the sex act that exceeds the project of domination or submission, specifically in the transformative act of recognizing one's bondage.

The primary mechanism available to the slave for transformation out of the terror of slavery is sex as work. In other words, sex becomes a form of work that introduces the possibility of transformation. In Mandingo, the slave performs work in and through sexual service. Sexual service constitutes their thinghood in slavery. If, as Alexandre Kojeve reflects, the slave transforms himself through the independence of "work," Mandingo 's work of sexual service is the mechanism through which the slave can progress. Sex is the work slave bodies produce for the master in Mandingo. Sexual labor replaces plantation and field "work" tying master to slave. Sex is the labor produced in bondage and is therefore that which "holds the bondsman in bondage; it is his chain from which he could not break free in the struggle, thus proving himself to be dependent, to possess his independence in thinghood."14 If sex is the work of the slave that benefits the master on the plantation, it is sex which "forms and shapes" self-consciousness. Kojeve describes the Hegelian process of becoming "[t]hrough [this] work [so that] the bondsman becomes conscious of what he truly is...Work...is desire held in check, fleetingness staved off ; in other words, work forms and shapes the thing ."15 The potential process in which the slave can embark on a transformation out of slavery is through [End Page 53] sex as subjugation and reclamation. Sex makes slave subjects who transform themselves by claiming entitlement (e.g., when Ellen negotiates freedom for her child) and pleasure (e.g., when Blanche and Mede experience orgasm). Sex also produces objects—mixed race chattel, holding slaves into bondage while threatening the very order of slavery that prohibits interracial sex.

The Master and the Wench: "...put your eyes on me... look at me straight into my eyes." Video frame enlargement.

Master-Slave Sex Acts: Paradoxical Freedoms

What does it mean that the very system that hails slaves into subjection enables the possibility of freedom? The hypersexual racial mythologies re-emerging in this formulation is precisely what makes it so attractive and so arousing to viewers. Seduced into the romance of new looking and new corporal relations, we follow the narrative of the sexual scenes in Mandingo's sexual scenes, but are not meant to ask if such moments of mutual recognition can truly be viable possibilities between slave subjects.

I return to the two sex scenes so as to question the possibilities of freedom opened up by master-slave sex acts. Hammond asks Ellen if she wants to perform sexual service for him, as if she had a choice! Her scripted response is as follows: "I like you, sir. I want to please you." Acting counter to the norms of sex practices in slavery, he kisses her on the mouth and encourages her to "look at [him]." This moment is constructed as a romantic meeting between two who are not meant to come together in love. The audience is meant to [End Page 54] swoon. The film is sexy because the characters mutually recognize each other in ways not sanctioned by slavery but burgeoning in the contemporaneous era. The scene romanticizes and eroticizes the racial terror of master-slave sexual relations with its representations of tenderness. This transgressive sexual scenario is attractive not only for imparting anew the Hegelian analytics of dependence and independence between master and slave but in its attempts to provide an explanation for contemporary interracial practices of sex and love. In the context of the seventies, it asks historically relevant questions about the function of interracial sex within the lingering and unfinished entanglement between sex and slavery present in society. Specifically, how do the legacies of such desires configure in the burgeoning occurrence of mixed marriages? How does the American racial past haunt intimate relations in the present? How do interracial babies function within rigid social orders?

In Mandingo, the two who struggle against each other's difference instead affirm each other's insufficiencies and dependencies within a system of dehumanizing brutality. In effect, the black man and white woman meet tenderly as an exceptional moment within absolute violence. As independent self-consciousness, they mutually depend on the other to constitute themselves. His slavery supports her mastery. Her mastery depends on his slave's confirmation. Mandingo eroticizes this relationship of power so that the possibility of unlocking the master-slave dialectic transpires in the bed.

The sex scenes between the master and the wench eroticize racial difference as well. The light flickers from a fire and makes her dark skin glisten and his white skin brighten. Certainly, sexually overdetermined racial subjects who find liberatory promise in sex implicates problematic racial mythologies. This is precisely the arousal sold in Mandingo. Sex between racial others sells in an era of racial disharmony. Or race sells in an era of sexual confusion. The master gently commands her to raise her head out of her deferential posture that signals her position within slavery. He permits her illegal gaze upon him. He tells her to "put your eyes on me... look at me straight into my eyes. She protests, "Niggers don't" look back. The master breaks with the gaze allowed in slavery when he says, "You can look at the white man in the eye if told to do it," then even more tenderly, "if asked." At this moment, race is forsaken so [End Page 55] as to construct normative and romanticized gender roles: a powerful man is gentle to a powerless woman. She plays her gender role as demure, shy and waiting for instruction. With his hands gently directing her gaze, he commands a new form of looking relations to occur between them. The scene is deliberately racial in its titillation: a black woman acts as a proper (white) woman. In their meeting of gazes, she lets loose a tear that makes her vulnerable and normatively female. She is seemingly struck by the striking emotional power of looking outside the sanctions of the law. She is met with the master's own new found and apparently self-disconcerted gaze. Their looking relations are transformed from a panopticon situation; the white man does not punish her looking but allows his own looking to be challenged. He transforms his own looking beyond conferral of her object status.

Seemingly, the very notion of absolute mastery comes to be questioned by the master who gives up his power (albeit momentarily) to the slave through the power of physical touch and its emotional meaning. The black woman slave as sanctioned by the master comes to stand in for the white woman as his surrogate wife. Despite his father's discouragement and disapproval of "tenderness" towards Ellen, Hammond gives her presents "good enough for a white lady." He insists on transgressing the rules of his mastery. Indeed, he bestows the same presents upon his wife with much less expense of emotion. He pours emotional investment onto his relationship with his wench. He takes Ellen on his trips outside the plantation and leaves his wife Blanche to rot in the house without his attention. Ellen, unlike his wife, receives assurances of his devotion and commitment. Even if Blanche is pregnant, Hammond guarantees Ellen that "No one, black or white, gonna take your place." She takes her place as his more legitimate partner in terms of an emotional marriage. As such, this relationship presumably defiles the system of domination in slavery, because the master no longer annihilates the slave to a certain death in life through her slavery but instead interrupts, or at least puts into question, her domination with affirmations of her value in life.

Attributing agency in the life of the enslaved is a contemporary historical and ethical dilemma. Is domination in slavery so total that any small pleasures, although readable as resistance, are not only insufficient but mistaken? Is [End Page 56] sexual pleasure possible within relations of domination? In Scenes of Subjection, Saidiya Hartman emphasizes the problem of agency exemplified in assigning will to a subject who has no rights in the context of slavery. She argues that the "simulation of will disallows redress and resistance when slave subjugation is "determinate negation."16 But does not the lack of any will for the slaves reinscribe them into an unquestioned status of beasts of burden? Certainly, the crucial question is how to do the impossible measurement of agency without (1) obscuring the terror of slavery or (2) fulfilling Hartman's diagnosis of a'"spurious attempt to incorporate the slave into the ethereal realm of the normative subject through consent and autonomy."17 Consent, will, and choice are indeed questionable concepts in the context of slavery as racial domination. Yet sex acts in the film show both slaves and masters as subjects-in-struggle within circuits of power.

The Mistress and Mandingo. Video frame enlargement.

Furthermore, both looking and corporeal relations seemingly transform anew between the Mistress-Mandingo. Against her tired and stained face, we see the Mandingo's large fragmented body. He is still, unresponsive, and frozen to the infliction of her touching. She strips off her robe and embraces him desperately in silence. After a long and painful pause, he surrenders, lifts her, and takes control of their sex by taking her to the bed for their carnal meeting. In a mutual act of vulnerability, he returns and affirms her self-exposure of displacement and alienation. The film constructs mutual participation in the sex act, in turning each other over and giving pleasure and kissing each other fully. In the previous sex scene Blanche performs with Hammond, she must pretend to fulfill the role of pure and high moral white lady. With Mede, there is supposedly [End Page 57] no need to pretend. She seeks recognition that Hammond did not give her. She finds pleasure through the forbidden sex act that further secures her place as an impure mistress. In effect, through the filmic construction of their sex as love, they meet in an ecstasy that transports their psyches momentarily into a world outside their racial roles. Although liminal, they meet sexually in recognition of their mutual displacements within the alienating system of slavery. A liberation of self-consciousness embodies in carnal sex so that their pleasures purportedly introduce possibilities for agency. Their resistance occurs in sex, the very site of their subjection.

What supposedly occurs here is a mutual sacrifice of selves in which they recognize and meet in a sexual act that I describe, in Judith Butler's words, as not "purely consumptive" but "becomes characterized by the ambiguity of an exchange in which two self-consciousness affirm the respective autonomy (independence) and alienation (otherness)."18 A meeting between the two reveals their independence from the master's grip. In a sense, they overthrow the master's control of their bodies when they experience the independence of pleasure for self. The power of this transgression is in the possibility of realizing a liberated self-consciousness.

The new relationship between transformed subjects cannot stay contained within secrecy. In subsequent scenes, mistress Blanche and the Mandingo Mede avoid each other's gaze as suspect subjects in the master's presence. Looks of recognition based on a shared fear of discovery pass between them. Her sexual cravings for intimacy fulfilled, she no longer lays open her hunger for recognition onto the master. She no longer drinks alcohol nor looks like a haggard mess. In effect, her transgression immediately garners her power into a new self-certainty so much so that both masters are intrigued by her new independence. The centrality of the master, for relating all selves in the system of slavery, is redirected in this case from mistress to slave, thus skipping mediation by the master. The slave affirms the mistress' selfhood with his own recognition and vice versa. They share a secret from their master and in effect, circumvent him, making him superfluous. Each sex act they repeat questions the master and slave's independence and dependence. The new relationship troubles the master's certainty in master-slave relations. [End Page 58]

When the Mandingo's sexual acts exceed the master's laws at moments of recognition in sex, the independence of that action leads him to discover his own self-consciousness. The independence of his sex acts defies the master's claims on his self-certainty. The slave begins to exist for himself; his participation in sex acts outlawed in slavery transforms him. The scenes of racial disruption through sexual tenderness help slaves see potential freedom through a seeing of the master as similarly alienated other. This re-recognition is the transformative experience of disallowed pleasures. In Mandingo, this mutual recognition makes outlaw sex a racially liberating act. If ecstasy is the process of losing oneself, the self surrenders as a sacrifice to the possibility of re-recognition in and through sex. When the slave recognizes the bondage of his self-consciousness to the master as fallible, protest against slavery is made visible.

Conclusion

However, we should be careful about buying the romance of freedom sold in Mandingo. In both transgressive situations of master-slave sex acts, Blanche and Hammond's imperfections lead to the betrayal and demise of mastery. Similarly, in the film's logic, Mandingo and Ellen must be punished for trespassing the boundaries of their enslavement and for engaging in the possibility of racial and sexual transgression. Sex both ensures slavery and undermines it in a complicated formulation of power. The potentiality for freedom presented in Mandingo is paradoxical; it presents sex as the way to freedom from slavery as it simultaneously enmeshes slaves further into servitude. By way of the master-wench and mistress-Mandingo relationships, the film disrupts the master's self-certainty and the slave's bondage so as to assert how sex opens up possibilities for de-stabilizing the systemic totality of slavery's domination.

All the while, the sex scenes between masters and slaves occur within the laws of the slave system while appearing to be in the semblance of transgression. Hammond orders Ellen to new relations of recognition in sex. Ellen is surreptitiously seduced into a position of taking power from the master. Mede, who must have sex with Mistress Blanche, is in a similar position as Ellen. While the masters' dictates open up the possibility for freedom through new relations [End Page 59] or freedom from the death in life that slavery entails, they also demonstrate how slaves are thoroughly enmeshed in servitude. Through sex, the master creates a paradox so as to get out of the master-slave impasse. Both masters Hammond and Blanche demand for the slaves to rewrite the power that inscribes them all into slavery and mastery. While the slave cannot initiate new relations in slavery, the masters are never supposed to give up their mastery. The slave, who must agree with the master, is placed deeper within the world of slavery for fulfilling the desires of the master. Whether slaves disagree or agree to the master, they face certain death. The paradox of mastery and slavery requires the surrender of power as a destabilizing force and the notion that the site of the slave's complete powerlessness also comes to be the site where freedom is possible. Yet, freedom from slavery is fleeting as ever.

Celine Parreñas Shimizu is Assistant Professor of Film and Video in the Asian American Studies Department at UC Santa Barbara. Her recent publications include forthcoming articles with Helen Lee on Asian American Film Feminisms in SIGNS (2004) and “Theory In/ Of Practice” in PINAY POWER (Routledge, 2004). This paper is part of her next book project Race and the Hollywood Sex Act.

Notes

1. Nelson George, Blackface: Reflections on African Americans and the Movies (New York: Harper Collins, 1994), 62.

2. Donald Bogle, Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies and Bucks (New York: Continuum, 1993), 243.

3. Ed Guerrero, ed., Framing Blackness: The African American Image in Film (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993), 31.

4. Guerrero, 35.

5. Robin Wood, Sexual Politics and Narrative Film: Hollywood and Beyond (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), 272–6.

6. Elaine Scarry, Elaine, The Body In Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), 56.

7. bell hooks, Reel to Real: Race, Class and Sex at the Movies (London: Routledge, 1996), 197.

8. hooks, 198.

9. Michel Foucault, Michel, Discipline and Punishment (New York: Vintage Books, 1977), 197–202.

10. See W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co., 1903); [End Page 60] Frantz Fanon, Black Skins, White Masks (New York: Grove Press, 1967); Orlando Patterson, Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1982); and Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993).

11. G.W.F. Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit, trans. A.V. Miller (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977), 114, para. 187.

12. Hegel, 119, para. 196.

13. Hegel, 115, sec. 190.

14. Alexandre Kojeve, An Introduction to the Reading of Hegel: Lectures on the Phenomenology of Spirit (New York: Basic Books, 1969), 48.

15. Ibid.

16. Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self–making in Nineteenthcentury America (London: Oxford UP, 1997), 52–3.

17. Ibid.

18. Judith Butler, Subjects of Desire: Hegelian Reflections in Twentieth Century France (New York: Columbia University Press, 1987), 51.