The Origins of the Food DesertUrban Inequality as Infrastructural Exclusion

This article develops the concept of infrastructural exclusion as a form of urban inequality through the case of the origins of the food desert in Philadelphia. Infrastructural exclusion refers to the reorganization of spatial and material interdependence into a semi-autonomous and path-dependent force that separates resources from those reliant on them. Building on archival research, it emphasizes how social problems arise out of taken-for-granted relationships between urban development, population settlements, and distribution systems. Grocery chains were interdependent with urban neighborhoods in the early 1900s, but they came to participate in a fiercely competitive industry during a precarious period of urban decline, suburban growth, and changes in transportation systems. New industry conventions about profitability, involving higher-volume supplies and lower transaction costs, became embedded into the sociotechnical infrastructure. The reorganization of infrastructural interdependence as a semi-autonomous force constrained local business decision-making, led to high rates of financial insolvency, and contributed to the overall decline of urban grocery markets. This approach to infrastructural exclusion provides insights into the causes of a unique form of urban inequality.

Introduction

Millions of people live in geographic pockets without access to supermarkets, a problem disproportionately impacting low-income communities and communities of color (Wrigley 2002; USDA 2009; McClintock 2011). Places without supermarkets—what many call “food deserts”—lack affordable fresh fruits and vegetables, as remaining corner stores are unable to procure and preserve wide varieties of fresh foods (Lucan, Karpyn, and Sherman 2010; Dannefer et al. 2012). This article uses the case of the food desert to demonstrate the role of infrastructural exclusion in producing urban inequality. It develops the relationship between [End Page 1285] organizations and infrastructures that facilitate, or in this case dislocate, urban interdependence.

Infrastructure operates according to a foundational sociological principle that certain features of everyday life are “seen but unnoticed” (Garfinkel 1967). It permeates so fully into daily life that it falls into the invisible background (Star and Ruhleder 1996; Edwards 2003). Public access to resources like food, water, and electricity depend on infrastructures connecting different social groups and geographic places. Not until people experience breakdown—limited access to clean water, electrical blackouts, or the loss of grocery stores—does infrastructure become seen as a public problem (Bowker and Star 1999; Graham and Marvin 2001).

The origins of the food desert are rooted in the reorganization of public and private infrastructures dating back to the 1930s in response to the changing spatial structure of population settlements and distribution systems. Private companies were forced to navigate the uncertainty of new forms of social and technical interdependence between suburbanization, highway development, automobile and trucking mobility, and larger storage warehouses and retail markets. The reorganization of infrastructural interdependence into a semi-autonomous force led to fierce competition, economic mistakes, and financial insolvency among large and small companies alike.

Studies of urban inequality stand to gain theoretically and empirically by focusing on the reorganization of infrastructure as the connecting process between everyday experiences of deprivation and political-economic patterns. Archival research yields findings about how Philadelphia’s four largest grocery chains adapted to changes in the social and spatial environment. Despite attempts at building stores within city limits, including in segregated black neighborhoods, all four companies succumbed to infrastructural pressures based on regional distribution and suburban supermarkets as the most profitable model. Companies were forced to close down dozens of less profitable urban stores during a precarious period of change, giving rise to infrastructural exclusion as a form of deprivation in an era of advanced capitalism.

Infrastructural Systems and Urban Development

Infrastructural systems make it possible to move materials and people between places, thus enabling population growth and market formation (Jackson 1985; Cronon 1991). As the link between sites of production and consumption, distribution infrastructures have influenced the health of local communities (Graham and Marvin 2001; Gandy 2002). In the United States, the sociotechnical relationships underlying the supply of key resources have expanded over time. Studying these expansions reveals how distinct resources become integrated and taken for granted in everyday life. The regulation and standardization of infrastructural systems promotes equitable access of some resources but not others.

In advanced capitalist countries, large infrastructural systems like water and electricity have become so pervasive that few live beyond their reach (Hughes 1987; Graham and Marvin 2001). These systems have attained near-universal coverage [End Page 1286] into “networked homes” (Gordon 2016). Local problem-solving gave rise to technical innovations, but over time “system builders” incorporated various adaptations into routine platforms (Hughes 1987; Edwards 2003). Public subsidies for regulating and standardizing these distribution systems facilitated equitable access.

Yet infrastructure is more than a stable “system of substrates—railroad lines, pipes and plumbing, electrical power plants, and wires” (Star 1999). Private firms, governmental organizations, and populations can also become interdependent through incremental and contingent sociotechnical expansions (Bowker and Star 1999; Molotch 2003). While food distribution is essential to human reproduction, it is not generally considered a public infrastructural system. Instead, the widespread mass-merchandising food system evolved as a hybrid sociotechnical arrangement of public and private interests operating at different scales.

The history of the food system includes moments of centralized state planning of different aspects of production, distribution, and consumption. The US Farm Bill has widely subsidized growers of commodity crops like corn and soy, which has stabilized the economic pursuit of high-volume manufacturing of thousands of processed and packaged products. On the consumer side, low-income families have received benefits through the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Department of Agriculture (USDA) have also established product safety and quality standards.

Goods distribution also received early public support to facilitate market connections. Initially the federal Bureau of Public Roads was housed in the USDA, before moving to the Department of Commerce and ultimately the Department of Transportation. The bureau oversaw national road and highway construction to improve commercial interdependencies. Over time, policymakers replaced local ad hoc road construction with “exacting engineering standards” to better integrate rural farmers and urban markets into a “national consumer culture.” A combination of state and federal financing led to more than three hundred thousand miles of roads and highways by 1930 (Hamilton 2008). System-building continued with the passing of the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, which further paved the way for suburban growth, public dependency on cars and trucks, and new economies of scale (Jackson 1985).

Public investments in roads and highways opened up more flexible product mobility options. Yet food distribution remained distinct from publicly regulated utilities, in that the government did not establish clear standards for equitable access. Instead, private companies navigated the competitive terrain of changing distribution methods and new territorial developments in the suburbs and beyond. Organizational decision-makers were forced to adjudicate between technical innovations, market formats, and market and warehouse locations. As the mass-merchandising system solidified, it constrained options available to grocery corporations and shaped a unique form of urban inequality.

Urban Inequality as Infrastructural Exclusion

Infrastructural exclusion occurs when sociotechnical interdependence develops into a semi-autonomous and path-dependent force that generates unequal access [End Page 1287] to resources. Several perspectives about the emergence and persistence of urban deprivation locate infrastructural development as an outcome of political-economic organization. For instance, scholars identify macro-level political-economic policies and organized neoliberal ideological regimes that have reconfigured global capital flows and local territorial development. The macro political-economic process is seen as causing uneven infrastructural expansion (Harvey 1982; Massey 1995 [1984]; Brenner and Theodore 2002).

Scholars of growth machines shift the political-economic level to place-based coalitions. Powerful actors are described as making strategic choices about infrastructural projects that advantage some local groups over others (Logan and Molotch 1987; Pais and Elliott 2008). Political-economic perspectives also provide background explanations of urban isolation in micro-level ethnographies. Abandoned lots, boarded-up factories, and neighborhoods with few amenities contextualize fine-grained studies of emerging cultures of disorganization and reorganization in poor neighborhoods (Anderson 1990; Bourgois 1995).

Studies of declining retail and food access in cities adopt similar analytical approaches. Some studies bridge together changes in capitalism and inequality through macro-level political-economic theories of urban disinvestment. For instance, large food corporations, responding to national and global policies, are described as strategically following the money out of cities (e.g., McClintock 2011). Scholars also focus on place-based “retail redlining,” in which retailers adopt deliberate discriminatory practices and avoid neighborhoods of poor people and people of color (Eisenhauer 2001; D’Rozario and Williams 2005; Kwate et al. 2013). Qualitative studies of food justice movements shift to the micro level to address how people respond to and resist deprivation (Nairn and Vitiello 2010; Gottlieb and Joshi 2010; Kato, Passidomo, and Harvey 2014).

Infrastructural exclusion, although distinct from these approaches to urban inequality, also complements them in important ways. Infrastructural transformation does not solely stem from strategic political-economic goals, the domination of large corporations over smaller businesses, or ideological global regimes over community interests. Rather it involves an incremental, highly competitive, and economically contingent process of inscribing organizational routines into changing systems. Infrastructural exclusion emphasizes how sociotechnical relationships materialize into a semi-autonomous and path-dependent force that compels organizational mistakes and unanticipated consequences.1

Historical sociologists argue that path dependency emerges from contingent circumstances or critical events (Sewell 1996; Mahoney 2000; Mahoney and Thelen 2010). However, key mechanisms—in this case, infrastructural interdependence—reinforce the adoption of certain economic conventions over others (Mahoney 2000). The following analytical objectives demonstrate how this infrastructural perspective explains unequal access to goods. The first shows how contingent circumstances—the Great Depression, transportation innovations, and suburban development—generated competing models of distribution that provoked uncertainties among decision-makers. The second examines how organizational decisions became inscribed into the relationship between public and private infrastructures. The final objective demonstrates how infrastructural [End Page 1288] interdependence constrained decision-making about market development, led to corporate financial collapses, and created underserved spaces. Together these objectives underscore how meso-level mechanisms mediate between political-economic transformations and local experiences of deprivation.

Data

This article draws upon the collections of Temple’s Urban Archives (TUA), Hagley Museum and Library (Hagley), Philadelphia Public Library (PPL), Philadelphia City Archives (PCA), US Censuses, and secondary sources. The data analysis connects different social and spatial levels by focusing on relationships between local organizational processes and regional and national distribution infrastructures and population settlements.

Collections of clippings from the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, Philadelphia Inquirer, and the online archives of the Philadelphia Tribune document local business narratives and activities: company transactions, executive reactions to market trends and population changes, and openings and closings of stores in the Philadelphia area between 1900 and 1980. Executives wrote local opinion pieces and memos to city officials that illuminate decision-making processes during periods of industry transformation. Newspaper articles also documented local processes and effects of corporate bankruptcies and insolvency that resulted in widespread store closings.

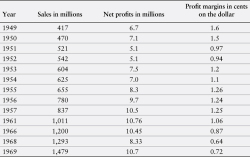

Company annual reports establish connections between local narratives and industry-wide processes, such as investments in changing building types, organizational approaches, and company profit structures. The most extensive annual reports are from the Philadelphia-based company Food Fair, between 1951 and 1970 (See table 1). Sample annual reports from the American Stores Company and A&P confirmed themes about changing corporate profit structures and organizational changes. Local newspapers also covered company profits and losses, which supplemented annual reports (See table 2).

Additional reports and secondary sources illustrate macro-level patterns of urban and regional development. The US Censuses provide evidence of population decentralization in Philadelphia’s metropolitan area. US Commerce Department and Federal Trade Commission reports, along with secondary historical sources, documented national and regional trends in the grocery industry, suburban development, and highway construction.

Philadelphia as a Changing Market Context

Philadelphia is a strategic research site to understand infrastructural exclusion. By 1920, Philadelphia was one of three cities in the United States—New York and Chicago were the others—with over a million residents. Like other large cities, Philadelphia’s growth decelerated after 1930, before its multi-decade period of population decline following 1950 (See figure 1). Suburbanization, deindustrialization, housing redlining, white flight, and middle-class outmigration isolated poorer African Americans (Hillier 2003; McKee 2008; Hunter 2013). However, [End Page 1289] Philadelphia was racially segregated before the food desert problem arose. In fact, Philadelphia’s four largest chains built supermarkets in segregated black neighborhoods (see figure 2). This point highlights the importance of studying the reorganization of infrastructural interdependencies as a distinct form of urban deprivation.

Food Fair, Inc., Sales Figures 1951 to 1970

Focusing on the four largest grocery chains in Philadelphia illustrates the transition from urban market interdependence to infrastructural exclusion. The American Stores Company, also known as Acme, was Philadelphia’s largest grocery chain in the early 1900s, ultimately growing into a national chain. With over a thousand markets in the region by 1917, its local motto was “No Resident of Philadelphia or Camden could live more than three blocks from an Acme market” (“Chain Store” 1917). The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company, also known as A&P, was the nation’s largest chain retailer. It had fifteen thousand stores by 1930, including many in Philadelphia. Penn Fruit, a smaller local chain, started as a greengrocer selling fruits and vegetables and grew into a full-service supermarket company. Food Fair, a regional chain headquartered in Philadelphia, became one of the fastest-growing companies on the East Coast. [End Page 1290]

American Stores Company Sales Figures 1949–1969 (excludes 1958–1960; 1962–1965; 1967)

Population changes: Philadelphia and surrounding nine-county area, 1850–2010

Contingent Circumstances and Organizational Uncertainty

Studies of suburbanization identify how changing transportation infrastructures influenced decentralized commercial growth. They show how public and private investments precipitated a new “drive-in culture” built upon highways, automobiles, parking lots, and shopping centers (Jackson 1985; also see Hayden [2004]). Yet a suburban commercial culture did not initially cohere as a distinct sociotechnical system. The chain grocery store was an urban neighborhood innovation of the early 1900s’ railroad age, but changing economic [End Page 1291] conditions, transportation systems, and population settlements complicated food-marketing goals.

Sample openings of Acme, A&P, Food Fair, and Penn Fruit supermarkets in Philadelphia, 1956 to 1976, in the context of neighborhood by percent black Source: Basemap provided by ESRI; Census tract data from Geolytics Neighborhood Change Database, 1970 US Census; supermarket openings from Temple Urban Archives clippings.

Contingent circumstances generated multiple decision-making options (Mahoney 2000). Events external to organizations created uncertainties (Vaughan 1999; Akrich, Callon, and Latour 2002). Organizational actors were forced to negotiate between established routines and new information (March and Olsen 1975; Levitt and March 1988; Cohen and Levinthal 1990). This section highlights two questions facing grocery executives: whether to adopt the supermarket system and whether to build stores in cities or suburbs.

Supermarketing or Not?

The decision to carry both fresh and dry commodities in stores altered food distribution. Early neighborhood grocers sold mostly dry goods and rarely obtained fresh commodities that did not keep well without refrigeration. The fresh system lacked the coordinated efficiency of dry goods distribution. Downtown produce wholesalers procured fruits and vegetables and sold out their stock daily to greengrocers and street vendors. In contrast, grocery chains developed thousands of stores within city limits by 1920, enabling inventive cost-cutting techniques for shelf-stable commodities like grains, sugar, tea, and coffee. They bypassed dry grocery wholesalers by storing products in large warehouses and [End Page 1292] delivering them directly to stores. They also standardized store layouts to cut down on time use in off-loading deliveries (Mayo 1993; Levinson 2011).

These efficiency techniques were not always well received. The largest national chains faced opposition from small-town business owners and farmers fearing corporate expansion. Congressmen representing these districts labeled them as monopolies. However, chains built alliances with struggling cooperative farmers and labor unions during the Great Depression, which slowed opposition (Ingram and Hayagreeva 2004). These new relationships allowed them to purchase fresh fruits and vegetables directly from farmers. They bypassed produce wholesalers just as they had previously bypassed dry goods wholesalers.

This transition did not immediately lead to a supermarket system. Chain grocers first introduced the “combination store” with more food varieties while retaining the clerk service of pulling products from shelves for customers. One out of three chain outlets was a combination store in 1929. The proportion grew to 50 percent by 1939 and 60 percent by 1946, at which point 15 percent of sales came from fresh produce (US Department of Commerce 1946).

Combination stores were bigger than previous corner stores, but not nearly the size of another innovation of that period: the “super market.” In 1930, King Kullen opened in Jamaica, Queens—the first East Coast supermarket. It advertised lower prices during the Depression. In an abandoned garage, Michael Cullen divided sections for dry groceries, meat, baked goods, and dairy. He leased remaining space to purveyors of produce, paint, hardware, and auto accessories (Charvat 1961). Cullen called his store “the world’s greatest price wrecker,” and followed the logic of “pile it high and sell it cheap” (Pelroth 2009). Big Bear, founded in 1933 by former merchandising and wholesaling executives, expanded these principles in a fifty-thousand-squarefoot abandoned auto plant in Elizabeth, New Jersey. Their high sales volumes and profits awed competitors. It took one hundred A&P stores in the surrounding area to match its volume (Mayo 1993).

The supermarket spread mostly as an entrepreneurial venture. The trade publication Super Market Merchandising, founded in 1936, provided management tips for new business owners. The Super Market Institute, a trade association, created “a degree of unity” in the industry (Charvat 1961, 1961–28). In 1936, 1,200 supermarkets operated in 32 states. Within the next year, the total almost tripled, to more than three thousand stores operating in 47 states (Zimmerman 1941). Introducing new economies of scale helped reduce the percentage of disposable income Americans spent on food from 21 percent in 1930 to 16 percent in 1940 (Pelroth 2009). “Cheap food” had arrived.

Retail leaders were divided over whether to invest in supermarkets or combination stores. Smaller chains like Food Fair and Penn Fruit, without national market infrastructures to convert, invested in the new supermarket approach. Food Fair started as a single corner store on Manhattan’s Lower East Side in the early 1900s. It completely converted to self-service supermarkets by 1935 and relocated its headquarters to Philadelphia. This early transition enabled the company to succeed in a crowded market space (Gillespie 1978). [End Page 1293]

In 1933, the Friedland brothers owned and operated 25 Food Fair combination stores. They observed changing market trends and began experimentation. In Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, they opened a ten-thousand-square-foot garage that warehoused more varieties and quantities than was typical of that era. They grossed $15,000 in the first week. They quickly opened another in Reading, Pennsylvania. Their two self-service supermarkets sold a higher volume than the rest of their 25 stores combined. They closed their smaller stores, moved their headquarters to Philadelphia, and began building supermarkets in that territory (Gillespie 1978).

Companies like Food Fair, and Penn Fruit, entered the industry at the right time. They gained consumer support in Philadelphia, which enabled them to advance into new suburbs. The Friedland brothers opened a hundred more supermarkets by 1948. They increased the rate of growth the following decade, leading the New York Times to label Food Fair the “fastest growing chain” in the grocery industry. Between 1950 and 1955, Food Fair opened an additional hundred outlets, and then a hundred more in the two following years. By the end of the decade, Food Fair totaled 367 stores in nine states, from Connecticut to Florida, with sales over $600 million a year. Just like national chains, they developed multi-state economies of scale, except at a much higher volume per store (Fetridge 1951; Nagle 1955; “Food Fair Plans Firm” 1955; “Food Fair Announces” 1958).

Executives studied trends in suburban development and consumer preferences to find new profit-making options. George Friedland, the president of Food Fair, wrote in 1953 that retail growth beyond the urban core was necessary due to high birth rate, low death rate, immigration, and a 2 percent total increase in the nation’s population. He established a store control and research department to prepare statistical reports on all dimensions of the industry: sales, profits, and expenses; consumer habits; and demographic and geographic reports on the changing population distribution (Food Fair Stores 1956). He noticed changes in where consumers bought food and in what they ate. The supermarket, he noted, was becoming integral to US consumption:

The bread and potato eaters of the ’30’s have become…the steak and vegetable eaters of today. Plenty of food and a growing demand indicate further increase in retail food sales and further gains in supermarket sales in particular. The supermarket, which has grown from comparative insignificance in the past quarter-century, now accounts for the major portion of total retail sales.

Friedland found a Wall Street firm to underwrite a growth program that transformed the company into a retail innovator (Sikora 1971; Nagle 1955). In 1955, Food Fair established a separate real estate company to develop and manage shopping centers within and beyond city limits. Food Fair Properties purchased land, constructed commercial centers, leased spaces to different merchants, and positioned their own stores as anchors in these shopping hubs. Within the first year of operation, Food Fair planned to construct 23 shopping centers in [End Page 1294] dispersed areas and developed a distribution infrastructure to continuously stock high volumes in all of them (Food Fair Stores 1956).

A&P and American Stores, two of the nation’s four largest food retailers, did not pursue the supermarket model at first. In 1936, national chains only cautiously experimented with it. They delayed—constrained by established organizational routines and prior investments in infrastructure. Initially, they converted dry grocery departments with packaged goods to self-service, because they believed consumers could handle branded products. Slowly, they introduced self-service into produce, dairy, baked goods, and other departments. As they opened new stores, they integrated the self-service philosophy into every department (Zimmerman 1941). Changing spatial and income dynamics of US population settlement caused them to convert, but they were too late.

American Stores (Acme) had been the largest chain in Philadelphia since the early 1900s and grew into the fourth-largest chain in the nation. In 1947, however, the majority of its stores still had clerks pulling products from shelves. Only 37 percent of its nearly two thousand stores were self-service supermarkets (Newman 1957). They fell behind in profit margins too. The company started to convert to supermarkets in 1941, but during the next two decades they still had not completed the transformation. By 1957, they finally moved full force, shrinking the number of stores from almost two thousand to about nine hundred, with 88 percent self-service (“Acme Chain 1955”; Newman 1957; “American Stores” 1957).

Similar to Food Fair’s earlier conversion, American Stores’ sales figures doubled despite the striking reduction in total number of outlets (see table 2). Yet reorganizing its infrastructure was expensive. In 1958, 95 percent of its stores were self-service supermarkets and the company reported its highest sales figures in history, but due to incurred costs it slipped to ninth in profit margins out of the nation’s12 largest grocery chains. In this competitive industry, cents on the dollar could inhibit economic success. In 1946, American Stores netted almost two cents on the dollar; by 1958, it earned only 1.25 cents per dollar. Paul Cupp, the company president, raised concerns about remaining clerk-service stores and costs associated with reorganization. “We’re not content with being ninth in profit margins,” he said. “We have more obsolescence than we should have in our stores.” He described plans to eliminate clerk-service stores by the end of the decade. “Ultimately only a few of our stores will not be self-service—in small, isolated communities where the old-fashioned store is profitable and desired by our customers” (Gaige 1958; “American Stores” 1957).

Urban or Suburban?

Between 1950 and 1970 the nation’s total disposable income more than tripled, from $206.9 billion to $629.7 billion (Grocery Industry Barometer 1970). Companies sought to profit from the largest concentration of consumers with the highest disposable incomes—those residing in the suburbs. Mass consumption, automobile mobility, interstate highway development, and suburbanization were mutually reinforcing. The more flexible highway-bound trucking economy [End Page 1295] replaced rail distribution, as it was better equipped to directly haul goods from “loading dock to unloading dock” (Hamilton 2008).

During this period, companies built supermarkets in both cities and suburbs, not strategically avoiding urban centers at first—and this was true even for the prescient expanders like Food Fair and Penn Fruit. The map in figure 2 shows that Philadelphia’s four largest grocery companies built new supermarkets in the city between 1956 and 1976, including stores in majority black neighborhoods. Even as suburbs grew, executives believed urban markets were profitable.

Food Fair, for instance, demolished the Surpass Leather Company factory at Ninth and Allegheny in North Philadelphia, constructing a large supermarket in its stead. It then opened a 27,000-square-foot supermarket in West Philadelphia in a new shopping center. They started a trend of building new urban supermarkets to replace multiple smaller stores, even developing a new distribution center in a formerly abandoned part of South Philadelphia. The eight-hundred-thousand-square-foot warehouse was accessible to new highway and bridge connections, could handle 115 tractor-trailers at a time, and serviced 150 stores in the region. Louis Stein, the company president, said, “We think we owe something to the city. We came to Philadelphia 22 years ago with a small warehouse at 58th Street, and Grays Avenue…doing a $6 million a year business. We expect to do $800 million in 1959” (“Food Fair Buys Surpass Plant” 1955; “Food Fair to Open Baltimore Av. Market,” 1958; “Food Fair Takes Big Site” 1959).

Penn Fruit followed Food Fair’s model (City of Philadelphia Memorandum 1953). Penn Fruit opened its first store in 1927 at 52nd and Market Street, operating as a fruit and vegetable vendor servicing this West Philadelphia neighborhood. Besides special attention to produce, the store’s founders, Samuel Cooke and Morris Kaplan, experimented with a sixteen-thousand-square-foot supermarket in 1932 at Broad and Grange Streets, claiming the first self-service supermarket in Philadelphia’s city limits. Adding to the produce, they offered seafood, meat, poultry, a delicatessen department, a bakery, and grocery departments with a broad assortment of packaged goods (“High Principles” 1956).

Penn Fruit’s first supermarket was uniquely “urban.” With no parking lot, it differed from suburban supermarkets, strategically fitting into this North Philadelphia neighborhood (Garrison 2013). Penn Fruit expanded on this approach. In 1941, the company opened at the intersection of 19th and Market Streets in the city’s business district—again without a parking lot. Still, they developed an information infrastructure for high-volume distribution. The company studied transportation statistics in relation to necessary sales volumes, determining that 170,000 trolley passengers and eighteen thousand automobiles came through this intersection daily. They converted this former wholesale warehouse into a 46,700-square-foot supermarket (Garrison 2013).

Penn Fruit’s urban model gradually became outdated, however. Samuel Cooke shifted his problem-solving framework in response to suburban development and changing modes of transportation. Cooke observed “the great resettlement of the population, increasing use of the automobile, greater emphasis on home living, an increase in the number of children per family, the home freezer, and a more casual way of life.” He argued that food executives must recognize [End Page 1296] “the full significance of automobile shopping” by providing more parking facilities to handle more people “converging from greater distance” and thereby operate as a “one stop shop” for more types of merchandise (Friedland and Cooke 1953). The company started building supermarkets in urban and suburban locations with parking lots.

By 1956, Penn Fruit had 41 stores and grew to more than seventy stores over the next two decades. The company expanded into the suburbs and as far away as Delaware and Maryland, but also opened new stores in Philadelphia, such as stores in majority black neighborhoods at 22nd and Lehigh Streets in North Philadelphia and 48th and Pine Streets in West Philadelphia. Penn Fruit also transformed its first store at 52nd and Market Streets to rival Food Fair’s new market, even as the neighborhood demographics changed around the store from white to black and the location stood at the cross-section of many black-owned businesses (“High Principles” 1956; “Center City” 1972).

The national chains followed the smaller local and regional companies, as changing population settlements opened up new economic prospects, including expansions into California and the West. American Stores acquired the California chain Alpha Beta, but it also opened Acme markets in suburban Pennsylvania and on Lehigh Avenue in the Kensington section of North Philadelphia—already considered one of the poorest and most racially segregated neighborhoods in the city—with 11,435 square feet of selling area, ten checkout booths, 102 feet of frozen food cases, and a parking lot for 83 cars. They opened up additional markets in other sections of the city too: Northeast Philadelphia and South Philadelphia, including one in a working-class neighborhood on 25th Street, between Reed and Wharton Streets, where 85,000 square feet allowed for 16,800 square feet of shopping space and a parking lot for 155 automobiles (“Acme Opens First Store” 1962; “Acme Opening Store” 1964; “New Acme Market Planned” 1965; “Acme Plans Shopping Mart” 1966; “New Acme Opened” 1966).

A&P sought to regain its market position by investing in cities and suburbs too. A&P introduced a giant regional market in the Springfield Shopping Center servicing residents of upper-income suburbs like Springfield, Media, Drexel Hill, and Haverford. The company also remodeled an outdated store in the majority black North Philadelphia Olney neighborhood, converting it to a 100 percent self-service market, adding air-conditioning, new flooring, a new meat department, additional dairy cases, grocery tables, fresh produce, and new checkout services (“New A&P Store” 1957; “Remodeled A&P” 1957).

A decade later, at the height of the Civil Rights movement, A&P partnered with Reverend Leon Sullivan. Sullivan, a local religious and political leader, initiated his “10–36 plan” to overcome abandonment and poverty in black neighborhoods. Congregants from his Zion Baptist Church contributed ten dollars for 36 months to finance new developments such as an apartment complex and shopping centers (Rhodes 1970). By 1967, 650 congregants had contributed to finance Progress Plaza in North Philadelphia. The 186,600-square-foot shopping center had parking facilities for three hundred cars and negotiated leases with commercial tenants, including A&P (“School in Shopping Center” 1967). [End Page 1297] Sullivan described this as the first partnership between a national food chain and a black-owned shopping center (“A&P Will Build Supermarket” 1967). Many neighborhoods were desperate for new services and job opportunities, and supermarket companies opened new outlets (see figure 2).

Reproducing the Suburban Supermarket Infrastructure

Contingent circumstances compelled firms to begin developing suburban supermarkets. Yet companies did not immediately close down urban access. Events and organized actions became inscribed into a new “sociotechnical ensemble” (Bijker 1995). Firms incrementally invested in an interdependent system made up of bureaucratic organizations, distribution warehouses, logistical technologies, trucking fleets, shopping centers anchored by supermarkets, and employee training in new technologies and product standards. This infrastructural system locked in profit-making conventions and forced firms into precarious economic positions. Urban stores became less viable in the process.

High-Volume and Low-Margin Distribution Infrastructure

Supermarket firms invested in information and technical infrastructures to maximize profits. They used demographic knowledge about where to build stores and warehouses and gained technical proficiency at procuring, consolidating, and moving thousands of commodities to hundreds of stores in multiple locations at the same time. They spent millions on building larger stores and warehouses and training employees to handle higher volumes of different kinds of goods: fresh, frozen, boxed, and canned goods as well as growing amounts of non-food products. The industry sold $40 billion worth of goods in 1952. By 1969, industry sales exceeded $62 billion (Stein 1970).

A&P executives described the company’s distribution system as its “heartbeat” and “intelligence center” that could “assemble goods from all over the world” and “anticipate” stores’ needs in many locations. A&P’s 1962 Annual Report states:

All suppliers obviously can’t deliver their wares to each A&P super market directly for a very simple reason: the hundreds of delivery trucks involved would surround every store with a monumental traffic jam. So, instead, suppliers ship their products to A&P’s warehouse…[thus] combining these items and re-shipping them to individual stores in the swiftest and most economical way. The company’s warehouses are strategically located close to the center of specific distribution areas to reduce this secondary transportation cost to a minimum, and they are also equipped to check all goods to ascertain that they meet our demands for high standards of quality.

Improvements in handling efficiency allowed companies to augment store sizes. Stores multiplied from ten to fifteen to more than thirty thousand square feet in [End Page 1298] less than a decade. Louis Stein, CEO of Food Fair in 1970, noted, “Another trend that will continue…is the increased size of the supermarket. The sales area of tomorrow’s supermarket may be 30,000 to 35,000 square feet, more than double the present-day store.” Larger stores allowed for more experimentation in developing and manufacturing new products. Stein said Food Fair will carry eight thousand items, “half of which were not available ten years ago” (Stein 1970). John Park, American Stores president, concurred: “Today’s market contains about 8,000 items, tomorrow’s will likely have twice that” (Park 1971). Stores already incorporated many food varieties, but new categories like “convenience foods” increased products designed for quick and easy preparation, including “pre-packed” meats and produce (Park 1971). Non-food commodities also spread: “health and beauty” aisles became highly profitable, and “hardware” sections incorporated paint and electrical home goods such as lightbulbs (Evening Bulletin 1974).

The high-volume and high-variety retail system cemented low profit margins. Tables 1 and 2 show how Food Fair and American Stores—a regional chain and a national chain—continuously increased sales volumes. However, when net profits stabilized in the mid-1960s, profit margins sank to less than 1 percent. Capturing higher sales volumes became critical to profit maximization with decreasing profit margins. Companies tried to stand out through experimentation, but they also had to imitate successful innovations so as not to fall behind. Faulty decisions and advancing positions by competitors easily led to losses in this infrastructural system.

The supermarket distribution infrastructure was expensive to maintain. Savings from high-volume purchases did not offset operational costs in certain types of stores and locations. The scale of distribution grew in direct tension with the costs to maintain profitability in aging markets. Three types of situations represent how the reorganization of infrastructure contributed to mass closings and the origins of the food desert.

Exogenous Shocks and Local Impacts

Large companies put pressure on smaller companies. Penn Fruit, the smallest of the four chains, went bankrupt in 1975 after suffering losses from a two-year price war. Some businesses cut product prices to increase store foot traffic. A&P slashed its prices in competitive locations like Philadelphia. They developed loss leaders, which sold below cost, making up profits through higher margins on other products and from more profitable stores in less competitive regions. For example, A&P paid 25cents for two tomato-soup cans, but then sold each for nine cents. Still identifying with the urban environment, A&P also converted some stores into a “warehouse economy model.” Stores displayed canned goods and groceries in shipping cartons and sold produce from crates in order to cut down on labor costs (Prokop 1972).

Price wars became localized, with extreme inter-organizational competition in cities like Philadelphia. Penn Fruit, with less access to reserves, struggled to maintain profitable sales volumes, losing customers to lower priced competitors [End Page 1299] and more aggressive companies like A&P Prokop 1972; Milletti 1975; Sama 1975). James Cooke, the company chairman, said in 1975:

Penn Fruit, which operated profitably for many decades, suffered severe losses because of a supermarket price war in Philadelphia that lasted for two years. Unlike our major chain competitors, the great bulk of our stores are in the Philadelphia area and we could not draw on profits from other sections of the country not affected by the severe local competitive conditions. Since the price war, Penn Fruit has not had the available cash resources to restore sales volume lost during that period of unprecedented competition. (Holland 1975b).

Penn Fruit was stuck between two poles. It needed to invest in infrastructural expansion to match the buying power and sales volumes of larger companies. Yet it faced aggressive pressures from larger chains, which augmented risks of such investments. The company could not get ahead. It closed almost half of its stores in 1975 alone after losing $32.2 million in that year (Drill 1976). By 1976, Penn Fruit could no longer afford to stock its shelves and closed down its remaining 35 supermarkets and warehouse facilities. Within the year, it had sold 17 stores to Food Fair. Eleven were in the city of Philadelphia, reflecting some executives’ continued belief that the density of smaller outlets could support a profitable volume of goods (Knox 1976; Prokop 1976; “Food Fair May Buy Penn Fruit” 1976; Herman 1975).

Innovations That Fail

Two years after purchasing the remaining Penn Fruit markets, Food Fair filed for bankruptcy. Trying to capture volume advantages, Food Fair tried to merge food and non-food industries into a new market type. They were decades ahead of the mounting trend of the 1990s when Wal-Mart opened “Supercenters” that integrated supermarkets and discount stores. Food Fair never mastered the distribution infrastructure supporting this model, and the company faltered.

In 1958, Food Fair supermarkets carried 20 percent non-food commodities. Executives experimented with increasing the proportion. The Evening Bulletin reported, “Food and non-food lines will be interspersed with each other so that a woman hunting lettuce will find herself looking at dresses and slips. If it’s ketchup she’s after, she may find herself walking through sweaters, shirts, stockings, summer furniture, irons, mixers, and other household items.” Executives justified the approach, claiming that the goal of super-marketing is “high sales volume under one roof” and carrying a non-food line of “disposable” products with “high turnover” is “an extension of the idea” (Newman 1958).

Not all agreed that this innovation was prudent. Cupp, the American Stores president, said, “From all the talk you hear…you’d think selling non-food items is a great, expanding deal. It isn’t that at all. Selling these items requires different talents, besides investment in inventories, space, and fixtures” (Gaige 1958). In other words, Food Fair needed sound organizational methods to build and manage the infrastructural interdependencies between manufacturers, distributors, [End Page 1300] and consumers. In 1961, Food Fair further invested in this infrastructure by purchasing J. M. Fields, a 79-unit discount department store chain. Over the next decade, the company worked to connect supermarkets and discount stores into the new retail model. Yet, between 1975 and 1977, in the face of continuing price wars, Food Fair lost $33.4 million. Executives tried pouring an additional $100 million from the more profitable food sector into renovations of this new merchandising approach, to no avail (Knox 1978).

Food Fair closed down smaller, less profitable stores to make up for its losses. In the Northern part of New Jersey, it closed 26 supermarkets without the volume needed to cover expenses. It closed 50 more stores in Long Island. Profits from 250 stores in Central Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina helped offset financial problems and stabilize stores in Philadelphia, the pride-filled location of its corporate headquarters. Food Fair purchased Penn Fruit, hoping to strengthen its local position (Knox 1978). Just two years later, however, Food Fair filed for bankruptcy. The company could no longer pay its bills. Distributors stopped making deliveries. Philadelphia’s largest non-financial corporation, the nation’s sixteenth-largest retailer, and the employer of thirty thousand workers in Greater Philadelphia declined in net worth from $140 million in 1974 to $25 million in 1979 (Eisen 1979).

Only half of Food Fair’s 88 Philadelphia outlets remained profitable. In its bankruptcy reorganization, Food Fair could not effectively convert its current distribution infrastructure designed for a larger multi-state network into a lower-volume model for its 44 remaining stores. Executives closed Philadelphia outlets and distribution centers. The company relocated its headquarters to Florida, prioritizing growth in the less competitive region (“Suppliers Deserting Food Fair” 1978; Gillespie 1978; Eisen and Herman 1979; Eisen 1979; Gillespie 1979).

Intra-Organizational Turmoil

Large national chains also fell behind, facing obsolescence in relation to the changing distribution infrastructure. Many companies competed at the national scale over buying power to maximize sales volumes and at the local scale for higher proportion of consumer dollars. This multi-scale approach forced regular adaptations and innovations (Goff 1978). Yet converting to higher sales volumes created problems in urban settings. Square footage cost more than in the suburbs. Building codes and the established built environment made renovations and expansions difficult.

Following a multi-decade effort to convert its distribution infrastructure, A&P reduced its number of stores from a high of fifteen thousand to two thousand by 1980. A&P was the most prosperous innovator of urban grocery stores, but the supermarket system challenged its profit-making formula. In 1975, it closed over a thousand stores, including 17 in the Philadelphia area and nine in the city itself. Jonathan Scott, chairman and CEO, said in 1975, “There is no longer any way we can support the burden of so many old stores. In recent years we have tried very hard against heavy odds to continue to serve local areas in [End Page 1301] many cities and towns. Now we must move ahead to complete the transition we started long ago” (Holland 1975a). As reported in the Courier Post, closing stores were “marginal facilities” and “considered obsolete” by “today’s standards” (“A&P to Shut Down” 1974). A&P’s roots as an urban-based corporation constrained its ability to adapt. Cornell agricultural economist Willard Hunt said in 1979 that A&P “was too late moving to the suburbs. When the company did move, the competition already was there” (Gillespie 1979). Facing decades of financial turmoil, A&P executives sold majority ownership to a German supermarket corporation (Gillespie 1979).

American Stores faced a similar scenario. Ida E. Brown of Philadelphia’s Germantown section owned nine hundred shares of company stock. At the annual shareholders’ meeting, she contested the closing of a store in her neighborhood. She said it caused “great inconvenience” to seniors, as the nearest remaining supermarket was too far to walk. John R. Park, chairman and president, responded, “There is no quick and easy solution to problems created for the elderly and poor by the closing of city supermarkets. I wish I could promise you a solution.” A spokesperson for American Stores said the fifteen-thousand-square-foot store in Germantown “wasn’t big enough to generate the volume necessary to make a profit under Acme’s price-discounting policy set up three years ago.” They planned to open 39 stores in the twenty-five- to thirty-thousand-square-foot range during the fiscal year and close an additional twenty smaller stores. Infrastructural interdependence compelled them to open larger supermarkets in areas with more secure sales volumes while closing less profitable outlets (Newman 1975; Dalton 1975; Herman 1975).

Infrastructural Breakdown Becomes Visible

The above example of the elderly woman from Germantown exemplifies a unique form of deprivation. The poor and elderly, those with limited mobility, faced hardships when urban interdependencies eroded. Areas once housing multiple markets were left with none, solidifying a period of consumer vulnerability. For example, a West Philadelphia neighborhood around Baltimore Avenue lost its Pantry Pride (Food Fair), Acme (American Stores Company), and Penn Fruit in just a couple of years. Only smaller, higher-priced stores remained. Convenience-store companies like 7–11 wanted to move into the neighborhood, but as Bennie Swans, president of the Baltimore Avenue Business and Community Association, said in 1979, “What the residents need in this area is another supermarket where they can purchase items at discount rates” (Smith 1979).

When infrastructural breakdown becomes visible, consumers, activists, and politicians see it as a public problem without necessarily understanding its deeper roots. The immediacy of vulnerability masks how sociotechnical interdependencies create deeply entrenched problems. Public officials accused declining companies of excluding poor neighborhoods. State Senator Freeman Hankins, representative of the Seventh District, discussed a Senate investigation into closing supermarkets: [End Page 1302]

I have an interest in eliminating some basic problems that face my constituents who find themselves without the services of food markets with competitive prices beneficial to them…The fact is that there is money in those places which people think are impoverished and negligible in terms of income potential, and that the state might be able to develop some plans to assure that people in West Philadelphia, Germantown and North Philly will be respected for the profit business people can make dealing with them. It is important that people cease having to walk a proverbial “mile” just for a loaf of bread.

Hankins pointed out that people in poor neighborhoods still spent money on food. Yet he missed the broader infrastructural context. Without public investment in equitable distribution, private firms sank costs into organizational and technical interdependence. New taken-for-granted organizational strategies became embedded into the distribution infrastructure. Following the period of market decline, executives started to assume that urban market development was less viable.

Corporate mergers gained traction following this period of collapse. Decision-makers in centralized corporate headquarters were separated from local consumer markets. Executives determined volume, advertising, sourcing, pricing, and distribution, which reduced the autonomy of in-store managers. Competing in multiple states and developing new logistical technologies further compelled standardized commodity lines and store layouts to maintain profitability. Infrastructural exclusion became a pervasive form of urban deprivation.

Discussion and Conclusion

The origins of the food desert represent a case of urban inequality as infrastructural exclusion. By examining the reorganization of public and private infrastructures, this article peeled back the “connective tissues” between different organizational actors and different levels of analysis. This form of urban deprivation was an outcome of recursive processes of building and expanding organizational and material interdependence (Molotch, Freudenberg, and Paulsen 2000; also see Elliott and Frickel 2013). Infrastructure emerged as a semi-autonomous and path-dependent force that generated organizational mistakes and unanticipated consequences.

Focusing on the role of distribution infrastructure in producing urban inequality has broad implications. It shows that exclusion is not necessarily an outcome of political-economic power struggles, ideological regimes, strategic decisions to disadvantage certain groups, or larger companies dominating smaller ones. Infrastructural exclusion can occur through contingent, incremental, and relational processes, mediating between the political economy of uneven territorial development and community experiences. Historical circumstances—the Great Depression, changing population settlements, and transportation innovations—gave rise to competing organizational and technical adaptations in cities and suburbs alike. Piecing together private and public infrastructures into an interdependent system involved organizational adjustments and fierce competition. [End Page 1303]

Companies made significant mistakes navigating the competitive path toward the mass merchandising system of higher-volume stores, shrinking profit margins, and lower transaction costs. Situated market actors negotiated between innovating to stand out from competitors, depending on existing organizational routines, and conforming to industry conventions. A&P—once the largest corporation in the nation—grew to prominence in the previous era as an urban grocery store, but it was slow to adopt emerging conventions. In contrast, Food Fair heavily invested in infrastructural innovations. It went too far beyond stabilizing conventions. Food Fair tried, albeit unprofitably, to combine multiple merchandising approaches into one organizational format over a decade before Wal-Mart mastered it.

Infrastructural interdependence incrementally crystallized into a semi-autonomous force. When industry conventions become embedded into the distribution system, they overwhelm corporate intent and strategy. Infrastructural interdependencies generated unanticipated consequences. Some companies went completely out of business, unable to make the necessary adjustments. Others filed for bankruptcy and restructured corporate goals around new industry priorities. All four companies in this study closed down dozens of stores at a time, following a period of opening stores in urban neighborhoods and suburbs at the same time. Reorganizing distribution networks gradually extended membership to new groups and places, but in turn marginalized others (Star 1995). Infrastructure emerged as a reinforcing mechanism of race and class exclusion, leaving behind innocent bystanders.

Future research could benefit from further investigations of how public and private organizations inscribe routines into sociotechnical interdependencies with substantial consequences for the public at large. Understanding the formation of infrastructural connections has further relevance in this age of privatizing public goods like water. Emerging public/private intersections may aim to achieve higher-quality and less expensive goods and services. However, the transformation of food distribution shows that such intersections can constrain equitable access.

Socio-historical investigations of this kind also face methodological limitations. Researchers are dependent on available historical materials that provide neither comprehensive listings of store openings and closings nor direct observations of backstage executive decision-making. Instead, the links between levels of analysis were made by studying executive discourses about changing organizational, material, and spatial conditions, archival documentation of sample store openings and closings, and narrative accounts of significant corporate changes and market declines resulting in batch closings. While this approach provides insights into the origins of the food desert, important questions remain about its persistence in many places.

Andrew Deener is an associate professor of sociology at the University of Connecticut. His research interests include urban development, neighborhood change, infrastructure, culture, and consumption. He is the author of Venice: A Contested Bohemia in Los Angeles (University of Chicago Press), a historical and ethnographic study of conflict and change in five adjacent neighborhoods. He is currently completing a book about the transforming relationship between urban infrastructure and the food system.

The author would like to thank Rene Almeling, Claudio Benzecry, Marcus Hunter, Rob Jansen, Annette Lareau, Harvey Molotch, Jeremy Pais, Jon Wynn, and anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript. I acknowledge the generous research support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health & Society Scholars program. Address correspondence concerning this article to Andrew Deener, University of Connecticut, Unit 1068, 344 Mansfield Road, Storrs, CT 06269, USA; phone: 860 486-4611; fax: 860-486-6356; email: andrew.deener@uconn.edu

Note

1. Multiple subfields now conceptualize humans and technologies as hybrid actors. Urbanists define infrastructure as “metabolic” and “lively”—it creates a new “metropolitan nature” that alters public health possibilities and community-level responses (Gandy 2002; Amin 2014). Moreover, economic sociologists examine capitalist goals [End Page 1304] of efficiency and profit maximization, not only as economic strategies, but also as taken-for-granted routines accomplished through sociotechnical forms (Callon 1998; Muniesa, Millo, and Callon 2007; Pinch and Swedberg 2008). Infrastructural exclusion builds on these perspectives, historicizing the organizational process by which infrastructural interdependencies become the structuring mechanisms enforcing adjustments.