Under the Counter, Under the Radar?The Business and Regulation of the Pornographic Press in Sweden 1950-1971

In this article, the process leading to decriminalization of pornography in Sweden in 1971 is analyzed. The interplay between the structural institutional level and company behavior is stressed, with an emphasis on business strategies. The article shows that the division between hard-core and soft-core pornographic magazines in Sweden was quite different than the development in the United Kingdom and the United States. It also shows how the business strategies used by hard-core pornographers challenged the obscenity legislation and regulation of national distribution, making them obsolete. Even though there was fierce competition between the pornography companies, producers formed joint alternative distribution channels crucial to the survival of the industry.

In the late 1960s and, more importantly, the 1970s, hardcore pornography became increasingly accessible to ordinary people in the Western world.1 Its development in Scandinavia is sometimes [End Page 350] discussed as a forerunner of this pornographic breakthrough; Denmark and Sweden were the first countries in the world to decriminalize pornography, and hard-core pornography markets developed early there.2 The Scandinavian market also received international attention for being something of a test case for this "permissive regulation."3 When other countries followed the Scandinavian example, larger markets became available to the already established Swedish and Danish publishing companies, and an international pornography industry started to take shape. Studies of this process, however, are still fairly limited. This article analyses the development of an underground pornographic publishing industry in Sweden during the 1950s and 1960s, the so-called porn wave in the late 1960s, and the process leading to its decriminalization in 1971. Special attention is also paid to the question of distribution and the possibilities for companies to evade regulations on pornography in general, staying under the radar of official surveillance. How did the Swedish pornographic press develop and change before 1971 and what strategies did these firms use to combat or escape the regulations? Starting with previous research and discussions about pornography markets and regulations, definitions of pornography and its genres and history, the article will then focus on Swedish developments and conclude by discussing the interplay between institutions and industry in this matter.

Previous research suggests that structural tendencies such as increased incomes, more leisure time, social democratic welfare, secularization, the so-called sexual revolution, and the reputation of "Swedish sin" created a breeding ground for a flourishing pornography industry in Scandinavia in the 1960s.4 While this article builds on these findings and acknowledges their importance, it focuses chiefly on firm behavior in relation to the specific institutional settings for [End Page 351] the pornography business. This focus makes it possible to bridge the gap and analyze the interplay between the more structural level and the firm and entrepreneurial level. While economic regulation research often focuses on economic growth, public ownership versus privatization and market failures,5 this study instead stresses the importance of focusing on other-than-economic regulations when studying the rise of specific industries. Whereas economic regulations often aim at facilitating (efficient) business, the regulation of pornography studied here was installed to prevent it. The literature on sexual regulations, on the other hand, has stressed its connections to morality, social norms, the boundary between permissible and impermissible, and gender and class relations, rather than the economic behavior of firms.6 By interpreting regulations and regulatory change and continuity as historically situated and dependent upon cultural and social change on the one hand,7 and by viewing sexual regulation as shaping the conditions for the pornographic business on the other, this study attempts to bring together business history and the history of sexuality.

Pornography is, and has historically been, a highly contested commodity.8 This means that companies publishing pornography share special conditions with, for example, the alcohol, tobacco, and gambling industries. As discussed by economist Kirk D. Davidson, these industries have common histories surrounded by regulation, resistance groups, and strong mass media coverage.9 US battles over controlling alcohol distribution involved an amendment to that [End Page 352] nation's Constitution and extensive violation of the ensuing ban, for example, whereas regulation of alcohol consumption through high taxation has become standard in Scandanavia. Both phenomena have generated substantial literatures.10 When explaining firm behavior in the pornography market, it is thus important to focus on the changing relationship between the industry and societal institutions. An acknowledgment of this mutual relationship makes it possible to analyze historically changing degrees of acceptance of pornographic products. It might also assist in explaining specific firm strategies used to balance the need to make a profitable product and still conduct business in a legal and accepted way.

Although pornography has a long and varied Western tradition,11 the "girlie magazine" is historically rather new. The nineteenth-century mass-produced erotic pictures (aka "French postcards"), for instance, undeniably featured not only naked women but also naked men and couples. The girlie magazine came as a response to consumer culture, technology, gender issues, and class politics, according to historian Lisa Z. Sigel.12 In both the United States and United Kingdom, pin-up magazines such as Esquire and Men Only introduced in the 1930s attempted to organize a consuming male audience.13 The new men's magazines could thus be seen in an economic history context, surfacing at a time when mass consumption was changing and reflecting (gendered) identities in the twentieth century. By creating new male consumer identities, further market segmentations became possible along gender, ethnicity, and class lines. The new white male identity, later developed in magazines like Playboy in the 1950s, reflected a consumer lifestyle separate from the feminine, by declaring what middle-class men should aspire to and do in their newly found leisure time.14 During the mid- twentieth century, men's magazines and pornographic magazines grew rapidly and used different strategies to attract consumers and advertisers. In her study of Playboy, sociologist Gail Dines describes the balancing act between, on the one hand, sexual explicitness in the magazines (to attract [End Page 353] consumers) and, on the other hand, the need to secure advertisers not wanting to be associated with pornography yet wishing to reach a supposedly affluent male audience. Openly pornographic magazines had a clearly inferior market position, lacking both the possibility to sell commercial advertisements and national distribution. Due to the absence of social legitimacy, the pornographic press was hence quite isolated from common business.15 Both Sigel and Dines stress that mass-produced and -distributed pornography is a rather recent phenomenon, growing out from a market of under-the-counter, low-quality pin-ups and stag movies.16 This article deals with the under-the-counter magazines that paralleled modern men's magazines, explaining how it eventually became possible to sell sexually explicit pornography over the counter.

Sources and Definition of Pornography

The pornographic press was to some extent underground during the 1950s and 1960s, leaving only some (sometimes unreliable) official documents about the industry.17 Unfortunately, its major entrepreneurs are now deceased and interviews that would otherwise have illuminated the trade from a more actor-oriented perspective are thus impossible to conduct. There are, however, some secondary sources involving interviews, which are used here. To gain insight into how the publishers responded to formal institutions, prosecutions of pornography publishers and preliminary investigations during 1950-1971 have also been analyzed.

To be able to quantify the development of the pornographic press, I have used a method based on the categorization used by the National Library of Sweden. The library is mandated to collect and preserve all Swedish publications, and has done so since 1661. The Legal Deposits Act stipulates that printers are to send one copy of everything they print to the National Library.18 Material deemed pornographic is put in a locked collection when delivered. A search in the library's database on this collection would thus ideally give a complete list of all pornographic magazines. However, some magazines are missing from the collection. Therefore, the lists of pornographic magazines and publishers from the library's collection have been supplemented by lists of pornographic magazines and publishers from the [End Page 354] distribution company The Swedish Press Bureau (Pressbyrån) and the Swedish Register of Periodicals (Svensk tidskriftsförteckning, published every other year).19 The definition of pornography used in this study is thus, briefly, whatever the library deemed pornographic when it was received and whatever the distribution company deemed pornographic when it was distributed. This definition makes pornography a variable concept that changes over time. The definition has also been supplemented with magazines that have been the objects of prosecution due to obscene content prior to 1971, thus including what has been tested as criminally pornographic.

The approach used here follows a body of literature that stresses that pornography is historically contingent and connected to the history of censorship. According to these researchers, regulations have played an important role in constructing the category of pornography by formulating limits to which the producers have related.20 However, pornography cannot be reduced to the methods used to combat it. Notions of shame and disgust connected to gender and class norms have also played a great part in shaping the content of pornographic material and in industry logic and development.21 Through examining librarians' and distributors' definitions together with prosecuted magazines, a definition closer to a common (historically unstable) understanding of pornography might be traced. Additionally, by resisting establishing predefined limit between pornography and nonpornography or hardcore and softcore at a certain degree of sexual explicitness, historical changes in tolerance toward sexual explicitness and different sexual expressions can be analyzed.22 For the regulations and their implementation, parliamentary documents and official [End Page 355] reports as well as secondary sources on the Pressbyrån regulation have been studied.

Institutional Settings

Prior to 1971, two institutions especially regulated the pornographic press.23 In the Freedom of the Press Act, printed material offending "discipline and morality" could be confiscated and the publisher prosecuted.24 The law prescribed that a review exemplary of every magazine printed or sold in Sweden be sent to the Minister of Justice or his representatives.25 An inspection was then carried out after the magazine was published. In addition, the monopoly-positioned distribution company Pressbyrån had parallel rules whereby magazines considered immoral could be denied distribution or receive a warning. Pressbyrån was a private company owned by the joint Swedish press, regulated by agreements between the company and the Swedish Newspapers Publisher's Association (Tidningsutgivarna). The Pressbyrån distribution monopoly was thus not formally regulated but was rather a consequence of its ownership status. According to the agreements, which accordingly were private and not part of the official freedom of the press jurisdiction, Pressbyrån was required to provide to buyers impartially all periodicals listed in the Post Authority register. Only if a magazine were considered offensive to public morality or decency by the Advisory Board of the Press (Pressens rådgivande nämnd) could Pressbyrån refuse to distribute it. Intervention by the Board could lead to a warning for the publisher, refusal to distribute a certain issue, or a total halt to distribution.26 The distribution regulation lasted until 1972, when the parallel paragraph in the Freedom of the Press Act was abolished.27 [End Page 356]

Swedish pornography publishers and magazines 1950-2000. Source: Compilation of data from the National Library Catalogue Regina and Libris (www.kb.se), Svensk tidskriftsförteckning, Chancellor of Justice Archive, a list of publications from the locked collection ("Förteckning av inlåsta publikationer") at the National Library of Sweden, The Pressbyrån compilation of disused magazines (Upphörda tidskrifter 1948-1988). Entrances on the market have been included in the total number of publishers at their entrance year, while exits have been withdrawn the coming year. This is to ensure that companies only existing for a single year are counted. A brief displacement may therefore affect the overall impression.

Transformations of and Changes in the Pornographic Press

A compilation of the source material described above is shown in figure 1. Data found only in the prosecution material are marked in order to avoid asymmetries, since regulation only lasted until 1971. The figure shows that the actors and magazines on the market increased intensely in the 1950s and 1960s, culminating in a strong "porn wave" a few years prior to the legislative amendment in 1971. Discussed by contemporary commentators, this increase in pornography on the market in the late 1960s caused great concern, especially among conservative and Christian groups and politicians.28 The figure also shows that the discrepancy between the publishers and magazines [End Page 357] found only in the prosecution material, and the pornography publishers and magazines in the library database was significant during the late 1960s. There can be several reasons for this discrepancy, but it indicates that some of the publishers were trying to evade authorities (and the library). Another reason for the high number of prosecutions at the time was a "porn raid," initiated by the Minister of Justice, justified with reference to the magazines' underground activities and sexual obscenity.

The sources show that several publishers prosecuted for publishing obscene material in the late 1960s were not organized as real firms but rather consisted of one or two people buying pictures and compiling them into magazines that they themselves distributed to sex shops in the major cities. The pornographic press in the late 1960s was thus to some extent a business activity without firms. This form of loose organization can be seen as a way of trying to escape repression. The need for the porn raid also shows that publishers had previously managed to stay under the authorities' radar.

Journalists David Hebditch and Nick Anning have described a decriminalization effect leading to increased sales directly after the legal amendment. After a while, sales returned to a lower, more stable level, reflecting the underlying demand.29 Following this argument, a growth in the industry would be expected after 1971 before diminishing. Although the figure does not show sales figures, the number of actors on the market suggests that the decriminalization effect preceded the actual legal amendment.30

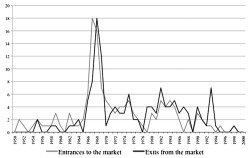

However, figure 1 does not explain anything about the magazines' circulation. Instead, it shows the diversity of the supply of pornographic magazines and the number of actors on the market, which indicates that the market was more concentrated at the start and toward the end of the period than in the middle. As figure 2 indicates, the number of publishers entering and exiting the market was considerable during the late 1960s, signifying a changing market prior to the legal amendment. Many publishers stayed in the market for less than a year; sometimes only one issue of a magazine was published, which can be seen as signaling high (and perhaps unrealistic) expectations of profitability. Regulation was more detailed on periodicals,31 however, which seems to have led to a diversity of [End Page 358] ostensibly individual titles. One publisher named his magazines Loving Sweden, Petting Sweden, Spanking Sweden, and Stripping Sweden and published them all in 1967. In the preliminary police investigation, the publisher denied that the different titles were in fact a cover for a periodical magazine.32 On the demand side, there was also a growing interest in sexual political issues that discursively framed pornography as a political strategy of sexual emancipation. This trend was also fueled by evening paper coverage of "sex wars" between religious conservatives on one side and sexual liberals and porn publishers on the other.

Number of pornography publishers entering and exiting the market 1950-2000. Source: Compilation of data from the National Library Catalogue Regina and Libris (www.kb.se), Svensk tidskriftsförteckning, Chancellor of Justice Archive, a list of publications from the locked collection ("Förteckning av inlåsta publikationer") at the National Library of Sweden, The Pressbyrån compilation of disused magazines (Upphörda tidskrifter 1948-1988). Entrances on the market have been included in the total number of publishers at their entrance year, while exits have been withdrawn the coming year. This is to ensure that companies only existing for a single year are counted. A brief displacement may therefore affect the overall impression.

The development (measured in number of companies and magazines on the market) is similar to the common pattern of the business cycle as an S-curve, here with an introduction phase during 1950-1965, a growth phase during 1965-1971, a maturity phase during 1972-1980, [End Page 359] and a decline phase from 1980 onwards.33 These phases broadly coincide with content transformations and international genre connections. A brief review of the content shows that the magazines classified as pornographic in the introduction phase can be separated into three main categories following an international pattern: pin-up, nudist, and so-called model study magazines. Both nudist and model study magazines were directed at specific consumers (nudist movement members and artists lacking nude models) but were also sold broadly as pornography.34 Under the guise of selling to these groups, the magazines were able to be far more "naked" than the pin-up magazines. However, they mainly featured naked women and did not depict sexual intercourse. None of the genres had much commercial advertising other than for sex-, nudist-, or artist-related products.35 During this period, Pressbyrån sales (i.e., domestic over-the-counter sales) of pornographic or pin-up magazines increased from 1.7 million copies of 4 titles sold in 1949 to more than 3 million copies of 14 titles sold in 196536—this in relation to Sweden's population of 7.5 million in 1960.37 None of the sources have reliable data on export volumes. However, the American Report of the Commission on Obscenity and Pornography stated in 1970 that the under-the-counter pornographic magazines on the US market primarily came from Scandinavia or were domestic copies of foreign publications. Imports from Scandinavia [End Page 360] were increasing, according to the Commission, but retail sales were still less than five million dollars per year.38

The US import of Scandinavian pornographic magazines undoubtedly emanated from a new genre of sexually explicit picture magazines that started to appear in both Denmark and Sweden during the growth phase in the latter half of the 1960s. This new genre was mainly directed at an international audience, with additional short texts in English and German. In both Scandinavian countries, the authorities tried to strike back against these magazines.39 In Sweden, the interventions were seen as quite paradoxical since a government commission had been appointed as early as 1965 to investigate whether the Freedom of the Press Act and the regulation on pornography could be liberated or abolished.40 Pornography publishers said that they took the appointment of the commission and the lack of intervention with a frequently discussed book containing pornographic short stories (Kärlek) as signs of a more liberal view from the authorities. In the so-called "porn raid" initiated by the Social Democratic Minister of Justice, Herman Kling, hundreds of domestic and foreign (mostly Danish) porn magazines were subjected to prosecution and seizure. Several of the magazines had a comparatively small circulation (around 5,000-10,000 copies) and were of poor quality, with black and white sexually explicit pictures stapled together to form a magazine. When the new decade approached, however, color-printed magazines became increasingly common. The content was sometimes only insinuated intercourse, with flaccid penises, spread vaginas, or dildo scenes, but increasingly also included close-ups of penetration. Just like in the earlier phase, these magazines lacked commercial advertising other than for sex-related content.41 The new (heterosexual) genre used the myth of the "Swedish sin" and the image of the sexually liberated Swedish girl, previously spread by famous Swedish [End Page 361] nude films, as a kind of marketing tool.42 In the late 1960s, a new genre of magazines directed exclusively at a male, homosexual audience also started to take shape.43

The high number of entrances to and exits from the market (figure 2) indicates strong competition and a transformation of the industry in the late 1960s. A closer look at the exits reveals that many were the newly started small magazines with sexually explicit pictures, along with the older nudist magazines and model study magazines. Most of the pin-up magazines stayed on the market during the 1960s, but their circulation figures clearly went down.44 The market thus seems to have become divided, to some extent, in the late 1960s: the new more explicit magazines directed at an international audience, and the older ones with short stories in Swedish directed at a domestic market. According to criminologist Berl Kutchinsky, the magazines directed at the domestic audience experienced a hard time during the Danish "porn wave."45 Although this was the case for some magazines in Sweden, publisher Curth Hson Nilsson, who still published his magazines in Swedish, claimed that he controlled around 40 percent of the domestic market in 1967.46 Even if he might have overestimated his market share, available sales figures show no significant competition from the "porn wave" magazines.47

The growth of the pornographic press also paralleled what has frequently been called the sexual revolution. Changed views on sexual issues surely encouraged a more liberal attitude toward the existence of pornography, by both authorities and the general public.48 The 1960s' sexually liberal rhetoric, such as calls for sexual freedom in terms of premarital sex and everyone's right to pornography was, however, not directly used by the Commission of Inquiry on Freedom of Speech or in the Government bill that preceded the legislative [End Page 362] amendment. Even if political promoters of legalization argued that proof of harm was needed if the obscenity regulation was to be kept, they mainly focused on the right not to be confronted by pornography and the need for regulation of dissemination as a compromise. These politicians also argued that censorship was incompatible with modern democratic society.49 However, many Members of Parliament claimed that pornography could harm its viewers and distort their sexuality. Pornography continued to be contested, and even though the controlling paragraph in the Freedom of the Press Act was removed, new regulations on unordered dissemination and window display replaced the old.

During the 1970s and 1980s, porn magazines moved toward higher paper and photo quality and genres became more strict, with (male) homosexual and heterosexual content clearly separated.50 A concentration of actors on the market became clear as publishers decreased, while the number of different titles on the market increased (see figure 1). Although a continued liberalization of pornography laws during the 1970s first extended the international market for Scandinavian pornographers, it later seems to have led to increased competition from larger foreign companies.51 During the 1980s, the pornographic press also started to suffer from the competition of VCR pornography.52

The Importance of Distribution

The right to distribute was, according to the Commission on Freedom of Speech, closely connected to the freedom of the press. It was argued that without the right to distribute, the freedom of the press was nothing but an illusion. They also pointed out, however, that the right to distribute and the freedom of speech could not be totally unlimited, with reference to the protection of certain groups or individuals in society, the maintenance of public order, and the general safety of the nation.53

The right to distribute was used by the pornography industry through ordinary distribution to sex shops, tobacco shops, and kiosks [End Page 363] as well as through mail order. The distribution of magazines in Sweden was mainly carried out by Pressbyrån.54 To achieve national distribution in the 1950s and 1960s, then, the pornographic magazines had to stay softcore to some extent, due to the Pressbyrån regulation. The Advisory Board of the Press was slightly stricter than the authorities. This meant that they exerted a kind of subsequent (privately regulated) censorship of distribution.55 The Advisory Board's interventions and warnings issued between 1959 and 1966 are summarized in table 1.

Interventions and warnings issued by the Advisory Board of the Press 1959-1966

As table 1 shows, the Board was more active during 1959 and 1960 than during the first half of the 1960s, and then gave a joint warning to several publishers in 1966. A new joint warning was sent out in 1968 as a consequence of what the Board viewed as increasingly offensive content.56 The Advisory Board also stopped single issues of [End Page 364] some magazines during the late 1960s.57 The parliamentary and public debates concerning pornography were intense across the whole period, with extended debates in 1954 and 1960. Often, politicians aspired to a kind of self-regulation of the press through the Advisory Board.58 An editorial in the liberal newspaper Dagens Nyheter, however, commented that it was improper to call the actions of the Board self-regulating; the publishers of pornography were not members of the Swedish Newspapers Publisher's Association and hence had no influence on the Board's actions. The Advisory Board was not acting within in the spirit of the freedom of the press, the editorial stated.59 The interventions by the Advisory Board can be seen as a result of relatively hard political pressure since legal interventions on the freedom of the press were much more politically sensitive. But the hopes for self-regulation, and expectations that curiosity-driven sales of pornography would diminish when the market matured, were soon dashed.

Though first-hand sources on the Advisory Board are scarce, newspapers reported that the 1959 interventions consisted of a distribution stop of two magazines, and that two planned magazines were never issued after being disapproved by the Board.60 The distribution restriction also led to parallel alternative distributing channels, something commentators had previously warned of. When Pressbyrån refused to distribute the magazine Ögat (The Eye) in 1960, the woman who published it decided to engage two retailers on commission, one for the area south of Gothenburg and one for the [End Page 365] area north thereof.61 The Board also acted against the magazines Piff and Paris Hollywood. The result of this action was that Piff and its sister magazine Raff were distributed together with Ögat while Paris Hollywood, an older pin-up magazine, decided to tone down its content to be able to maintain national distribution.62

The circulation of Ögat decreased from 13,000 to 10,000 copies after the Pressbyrån distribution stop, indicating that the intervention had a degree of economic effect.63 The Ögat case also suggests that there were no organized alternative distribution forms that the publisher could engage in prior to 1960; the woman employed the retailers herself. Even if circulation decreased as a consequence of the lack of distribution by Pressbyrån, the publisher gained an advantage when hired to distribute other pornographic magazines.64

The organization of alternative distribution channels through cooperation among pornography publishers made it possible for the magazines to directly challenge the legislation.65 Sources mention international distribution companies as early as the 1950s, and during the 1960s domestic distribution channels specialized in pornography began emerging, possibly lowering the cost of efficient distribution outside Pressbyrån.66 The edition of Malmö's Paris-News TV-Magazine in 1963 (consisting of 10,000 copies) was, for example, allocated for international distribution in Denmark, Western Europe, and South America through the company Sanko Norden (26 percent), retailers in Southern Sweden (12 percent), and one man in Gothenburg for distribution to the remainder of Sweden. The rest of the edition [End Page 366] was seized at the book bindery.67 Even if it is hard to know the status of the Gothenburg man's business, this example supports the idea that the international distribution channels developed earlier than the Swedish ones. The tendency toward alternative distribution is also significant in the data from the Post Authority record (the prerequisite for the right to Pressbyrån distribution) and in the Pressbyrån register compared to the pornographic press as a whole, as shown in figure 3.

Magazine titles distributed by Pressbyrån compared to the total number of titles on the pornography market 1957-1971. Source: Compilation of data from the National Library Catalogue Regina and Libris (www.kb.se), Svensk tidskriftsförteckning, Chancellor of Justice Archive, a list of locked-in publications from the National Library, the Pressbyrån compilation of disused magazines and the Post Authority's register (Postens inländska tidningstaxa) own compilation, complemented by the Pressbyrån register of disused magazines.

Figure 3 documents that many magazines were issued without having national distribution via Pressbyrån during the 1960s, with a first separation in 1962 and a second in 1967 coinciding with the "porn wave."68 Most of the magazines constituting this wave were thus privately distributed, which explains how they were able to challenge the regulation on obscene material. It is important to note, however, [End Page 367] that magazines denied Pressbyrån distribution were not necessarily removed from the Post Authority register. It is also likely that the Pressbyrån magazines had higher numbers of copies printed and that they represented a larger share of total sales than indicated by the figure.

Figure 3 also shows that there had been pornographic magazines outside the Pressbyrån distribution all along. The reason for this might be that they were small magazines sold primarily by mail order or that they simply evaded the authorities and did not apply for publication authorization (one of the requirements for joining the register).

Since the Advisory Board was significantly more stringent than the government authorities applying the Freedom of the Press Act, some pornography publishers did not even try to get Pressbyrån distribution in the late 1960s. The more advanced magazines were sold in special shops and by mail order, according to the Commission on the Freedom of Speech, who concluded that many of these magazines were unknown by the majority of the population.69 The distribution situation also affected retail, with sex shops having a far higher range of explicit magazines than ordinary kiosks and newsstands. Some magazines also had clearly limited geographical distribution, as at the end of the 1960s several publishers (together with an employee) actually drove himself or herself to different kiosks and sex shops to vend their magazines.70 In Stockholm and Copenhagen, streets like Klara Norra Kyrkogata and Istedgade gradually became famous sex shop districts that attracted customers and tourists.

In the sexually liberal political climate of the late 1960s, voices were raised criticizing the Advisory Board's interventions. Attorney Leif Silbersky, who defended several pornography publishers, even called the Board a "private censorship court," ruled by the conservative press through the Swedish Newspapers Publisher's Association.71 Pornographers also spoke out against the Pressbyrån intervention in news media. On the national television program Pressfönstret, Curth Hson Nilsson said he considered Pressbyrån's 1966 warnings an extortion threat: "And it is a threat because Pressbyrån is the only special company for press distribution that can efficiently deliver magazines to the readership at a low price."72 Pressbyrån defended their actions, however, claiming that it was necessary to react to content with detailed intercourse pictures, group sex, and animals [End Page 368] involved in sexual contacts.73 The pornographic press was thus further divided between softcore and hardcore when alternative distribution channels developed. Hard-core magazines separated from the rest of the Swedish press when it came to both retail and national distribution. Pressbyrån kiosks were also required to use discreet signage.74

The "Porn Raid"

The underlying story of the 1967 porn raid, authorized by the Swedish Minister of Justice, was the seizure of the first edition of a Malmö magazine called Orgasm. The publisher found it unfair that his magazine had been seized when other equally explicit magazines were being sold openly on the market. He therefore gathered a bundle of competing magazines (many of them previously unknown to the authorities) and handed them over, triggering further seizures.75 When Orgasm's publisher was interviewed in an evening paper, he agreed that magazines had generally become more daring: "But it is against our ideas in Sweden to stop porn. Also, the industry will regulate itself." Seizures were unnecessary, as people would soon be bored with the worst pornography: "The development will soon be reversed again," he stated.76 This kind of reasoning was also used by the Minister of Justice, Herman Kling. He denied that the porn raid was in fact a stricter attitude toward pornography: "We just wanted to tackle the worst and most disgusting. We have been careful concerning seizures. But now, I think things have gone too far: this is speculation [End Page 369] in the worst of sadism."77 The policy had previously been to let buyers "eat until they were full," in the belief that sales would then diminish. This had worked for a while, according to the Minister, but when circulation decreased publishers started to compete through content, which became much rougher. The porn raid was also an important step to reach publishers who neglected to submit inspection copies.78 Some pornographers commented on the raid, and questioned its intended effect. The seizures instead gave the industry "enormous advertising" through media coverage, according to one of them.79 The publisher of Orgasm also wanted definitive decisions: "There are many of us publishers who want clear answers from the Minister of Justice about the future. Are we supposed to go underground or will porn be like any other product in the stores?"80

The numerous prosecutions and the rich source material from police interrogations and investigations reveal some of the other strategies used by publishers. A common strategy, often used in combination with alternative distribution, was to simply refrain from submitting a review copy to the freedom of the press authorities (Tryckfrihetombuden). This was an illegal way of trying to stay under the radar and was one of the main reasons for the porn raid. The development of strategies whereby dummies were put in place as the legally responsible actors for magazines was a consequence of the Swedish penal systems' use of means-tested fines, based on the income of the offender. In Malmö, a Swedish city close to Copenhagen, one man registered as legally responsible for several magazines and different publishers. He had specialized in balancing between the legally accepted and the commercially successful. With his low-registered income, his fines were not very high when he was convicted because of a magazine's content.81 The seizures still had economic consequences on the pornographic companies, however, as they interrupted commerce. Some publishers therefore tried to retouch their pictures in order to make them less offensive.82 There was great [End Page 370] uncertainty among both officials and publishers about what kind of material should be punishable. Juries in different municipal courts developed separate practices about what they considered offensive. For instance, the Stockholm municipal court freed all pornographic magazines after 1967 whereas similar material led to convictions in smaller cities and towns.83 The parallel development in the film industry should not be underestimated. When artistic, yet sexually explicit films such as I am Curious Yellow (Vilgot Sjöman 1967) and Language of Love (Torgny Wickman 1969) were shown openly at cinemas to full houses, pornography publishers found it unfair that their magazines were considered criminal. Attorneys pushed this issue, and Leif Silbersky even took the whole court to the movies to see I am Curious Yellow, something he later claimed changed the practice in the Stockholm municipal court.84

In several ways, the raid was judged to have revealed that existing legislation was obsolete and unfair. The need for a revision of the Freedom of the Press Act was therefore considered urgent. Both the more frequent actions of the Advisory Board and the porn raid can thus be said to have had the opposite effect than what was intended; instead of combating pornography it made the industry more independent, with its own distribution channels, and helped forces arguing for a liberal revision of the Freedom of the Press Act. For individual companies, however, the interventions sometimes had lethal effects. It is also possible that the interventions accelerated the transformation of the industry, leaving only the more resilient sexually explicit color magazines on the market.

Conclusions

The Advisory Board of the Press can be seen as the main gatekeeper between acceptable and unacceptable publishing, whereby explicit pornography was locked out from the main distribution channel. Unlike developments in the United Kingdom and the United States, advertising seems to have played a minor role in the division between softcore and hardcore before the end of the 1960s. Although Playboy certainly served as a role model of a winning business concept for Swedish magazines, none of the major publishers used its mixture of broad advertising, national distribution, and soft-core sexual content [End Page 371] before the middle of the 1960s, when the men's magazines Fib Aktuellt and Lektyr entered this market segment and went on to enjoy enormous success in the 1970s. Unlike previous Swedish porn magazines and men's magazines with sexual content, these new entries had major (and thus accepted) popular press companies as publishers. By contrast, the magazines analyzed in this article did not have commercial ads other than for sexual products, and some also had a hard time achieving or maintaining national distribution.

In studying the development of the pornographic press, the importance of institutions becomes clear. But their implications for the pornography industry is of a quite complex nature. The regulation of obscene material and the stricter practice of the Advisory Board of the Press opened a market for other distribution companies specialized in pornographic magazines in the late 1960s. Regulation's intention and implementation were thus rather different from its consequences, a familiar situation. But although conservative politicians and Christian interest groups called for Pressbyrån's stricter enforcement, sexually liberal rhetorics encouraged acceptance of pornography and emphasized the obsoleteness of the obscenity paragraph. The relaxed application of this paragraph by some courts created a gap—allowing magazines to be legal without the right to national distribution. It was in this gap that the pornography distribution actors found their market. This, together with other strategies used by pornography publishers, seems to be an important reason why the "porn wave" preceded the legislative amendment. A more or less underground distribution system presumably also temporarily helped publishers who wanted to stay below the enforcement radar, allowing sexually explicit magazines to grow stronger in an environment out of sight of authorities.

The study of the business of pornography offers a new way to define (at least hard-core) pornography. Since ordinary Swedish companies did not want to be associated with pornography, the appearance of advertisements for anything other than sex-industry products and the possibility for national distribution could strike a boundary between softcore and hardcore. This could be seen as seeking a balance between achieving profit and risking goodwill, as support for the sex industry was (and is) considered ethically wrong. A study of how this balancing act changes over time could both say something about the press economy in general and reflect how limits of accepted sexuality have been historically and economically constructed. This further supports the idea that the business of pornography and the institutions regulating it are shaped as a consequence of pornography being a contested commodity. This specific situation has also resulted in a special kind of entrepreneurship, bordering on the illegal. [End Page 372]

Klara Arnberg is a PhD in Economic History at Stockholm University. Contact information: Department of Economic History, Stockholm University, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden. E-mail: klara.arnberg@ekohist.su.se.

Bibliography of Works Cited

Books

Articles and Essays

Magazines and Newspapers

Unpublished Work

Archival Sources

Legislative and Parliamentary Resources

Footnotes

This article is part of a project funded by Ridderstads stiftelse [The Ridderstad Foundation] and has been carried out at the Department of Economic History at Umeå University.

An earlier version of the article was presented at the fourteenth Annual Conference of the European Business History Association in Glasgow 2010.

1. Juffer, At Home with Pornography; Kendrick, The Secret Museum.

2. Hebditch and Anning, Porn Gold, 20; Pettersson, "Introduktion," in Dellamorte, Svensk sensationsfilm, 7; Kutchinsky, Law, Pornography and Crime, 50ff; Paasonen, Nikunen, and Saarenmaa, "Pornofication and the Education of Desire," in Paasonen et al., eds., Pornofication, 7.

3. Berl Kuthinsky's study of the effect of the Danish pornography legislation for the US President's Commission on Obscenity and Pornography in 1970 is perhaps the most famous and striking example of this. The results of the study have been highly contested, as Kutchinsky stated that the legalization of pornography did not result in increasing sex crimes. However, Kutchinsky also conducted research on the pornography market in Denmark at the time relevant to this article. Examples of international interest in the Swedish and Danish developments can also be found in international media coverage. See, for example, "Danes and Swedes Are Moving Toward Greater Sex Freedom," in New York Times, November 6, 1968; "When 'Porn' Becomes Corn," in Washington Post, April 19, 1969.

4. See for instance, Kutchinsky, Law, Pornography and Crime, ch. 3; Arnberg, "Synd på export"; Arnberg, Motsättningarnas marknad.

5. See for instance, Magnusson and Ottosson, The State, Regulation and the Economy; Millward, "Business and the State," in Jones and Zeitlin, eds., Business History.

6. See for instance, Weeks, Making Sexual History, 133-7; Fout, Forbidden History; Smith, Welfare Reform and Sexual Regulation; Nead, "The Female Nude," in Signs. There are, however, some interesting studies that deal with market outcomes of sexual regulations and vice versa. See for instance, Coulmont and Hubbard, "Consuming Sex," in Journal of Law and Society; Smith, "A Perfectly British Business"; Hoffman, "'A Certain Amount of Prudishness'," in Gender & History. Much of the literature on sexual regulation also primarily concerns prostitution. For an economic historical perspective on the regulation of prostitution, see for instance Svanström, Policing Public Women.

7. The field of research that emphasize the role of history for explaining regulatory change and continuity is connected to the works of Douglass North and the concept of path dependence. North, Institutions; Magnusson and Ottosson, Evolutionary Economics and Path Dependence.

8. For a discussion about pornography as a contested commodity, see Radin, Contested Commodities, 175-6. For discussions about historic battles over the introduction of pornography on the common market, see for instance Hunt, The Invention of Pornography; Kendrick, The Secret Museum; Sigel, International Exposure.

9. Davidson, Selling Sin.

10. Miron and Zweibel, "Alcohol Consumption during Prohibition"; Mäkela, "Uses of Alcohol," and Mäkela, "Attitudes Toward Drunkenness."

11. For a longer perspective on pornography history, see for instance, Hunt, The Invention of Pornography.

12. Sigel, International Exposure, 2. See also Larsson, "Utvecklingslinjer," in Gustafsson, ed., Veckopressbranschens struktur, 25. Larsson stresses that both modern men's and women's magazines are post-World War II phenomena. According to Larsson, pornography and gossip in the popular press are thus quite recent.

13. Breazeale, "In Spite of Women," 1; Greenfield, O'Connell, and Reid, "Fashioning Masculinity."

14. Breazeale, "In Spite of Women," 3.

15. Dines, "Dirty Business," in Dines, Jensen, and Russo, eds., Pornography, 53.

16. Sigel, International Exposure, 1-2; Dines, "Dirty Business", 38, 45.

17. Peiss, "On Beauty," in Scranton, ed., Beauty and Business, 18-19.

18. http://www.kb.se/english/services/deposits/ (accessed December 23, 2011).

19. The sources overlap to a great extent: Of a total of 301 magazines published in 1950-1980, 24, were found only in the Pressbyrån register, two exclusively in Svensk tidskriftsförteckning and an additional 14 in an internal document from the National Library from an earlier invention of the locked collection. See The Pressbyrån Museum, Upphörda tidskrifter 1948-1988; National Library of Sweden, "Förteckning över inlåsta publikationer." This means, then, that about 13 percent of the titles were found in one of these sources only. This figure is lower for the publishers, however, with only 10 firms found in only one of these sources, constituting 11 percent of all publishers. For the magazines and publishers found only in prosecution acts, see figure 1.

20. Kendrick, The Secret Museum, xii, 1-2, 95; Smith, One for the Girls!, 16-17; Hunt, The Invention of Pornography, 11.

21. Compare Waugh, "Homosociality in the Classical American Stag Film," 276; Williams, Hard Core, 14-15; Rubin, "Thinking Sex," 307-08; Ross, "Bumping and Grinding," 221-2.

22. This definition is thus different from the more stable definition used in many other studies where hardcore and softcore are used as genres separating "full visibility" from erotica. See for instance, Williams, Hard Core, 6-9.

23. In this article, the Douglass North definition of institutions as "rules of the game" is used. Although informal institutions are highly important in analyzing the changing legitimacy of the industry, formal institutions are in focus in this article. Compare North, Institutions, 4.

24. "Såra tukt och sedlighet," Swedish Code of Statutes (SFS) 1949: 105, 7 kap 4§, pt 12.

25. Swedish Code of Statutes, Freedom of the Press Act, Tryckfrihetsförordningen SFS 1949: 105, ch. 4.

26. See the Pressbyrån agreement [Pressbyråavtalet] from 1966 in the Swedish National Archive, Committee Archives, Commission of Inquiry on Freedom of Speech, Kommittén för lagstiftningen om yttrande och tryckfrihet 1965-1969, vol. 8. See also SOU 1969:38, 32-33.

27. Jacobson, "Nuet och framtiden," in Frick, Bergh, and Nilsson, eds., Pressbyrån, 161.

28. See for instance, Arnberg, Motsättningarnas marknad, ch. 3. See also Kuthinsky, Law, Pornography and Crime, ch. 4 for the parallel Danish "porn wave."

29. Hebditch and Anning, Porn Gold, 4.

30. A similar development was measured in Denmark. Kutchinsky, Law, Pornography and Crime, 83-5.

31. All periodical magazines had to apply for a special publication proof at the Ministry of Justice before publishing. See Swedish Code of Statutes, Freedom of the Press Act, Tryckfrihetsförordningen (SFS 1949: 105), ch. 5.

32. Preliminary investigation conducted by the Stockholm Police, in Swedish National Archive, Attorney General Archive, acts on common cases no. 237, 238, 239 and 268, 1967.

33. About the business cycle and its phases, see for instance, Porter, Competitive Strategy, 157ff.

34. Hanson, The History of Men's Magazines, 111; Bjurman, "Pop och pornografi," 264; Nestius, I Last Och Lust, 54; Strand, Sol, hälsa, glädje, 82-3. Compare Hoffman, "'A Certain Amount of Prudishness'."

35. Boulevard magazines like Pin Up, Paris Hollywood, and Piff contained advertisements for, for example, nude photoprints, pornographic literature, sex education, and medicines for both impotence and premature ejaculation. Hsonproduktion (publisher of Piff) also advertised for their own shop, Tobaksbazaaren, in Stockholm. Helios and Tidlösa contained advertisments for membership in nudist clubs, for a photo service whereby readers could send in photos for anonymous printing and for other (foreign and domestic) nudist magazines, books, and films. See for instance Pin Up no. 11, 1962; Paris Hollywood no. 1, 1962; Piff no. 24, 1958; Piff no. 7, 1964; Helios no. 12, 1964; Tidlösa no. 3, 1954. See also Bjurman, "Pop och pornografi."

36. Compare data from Swedish National Archive, Attorney General Archive, Transcript of letter to the Minister of Justice in Pressklipp enskilda ärenden (ÖIIb 18), RA, 3 with Swedish National Archive, Committee Archives, Commission of Inquiry on Freedom of Speech, Kommittén för lagstiftningen om yttrande och tryckfrihet 1965-1969, vol. 1, Protokoll från Kommittén för lagstiftningen om yttrande- och tryckfrihets sammanträde med Pressens rådgivande nämnd, 2 februari 1967. The data consists of some irregularities, which are further described in Arnberg, Motsättningarnas marknad, 92-5.

37. Statistics Sweden, http://www.scb.se/Pages/TableAndChart_26047.aspx (accessed December 23, 2011).

38. The Commission also stressed that the "adults-only" printed material was of far less importance than mass-market publications. The combined copy sales of all adults-only magazines in one year were less than one month's sales of Reader's Digest. The American market consisted of 80-100 publishers, of whom 20-30 were import factors. Some 100,000 packages of hard-core material were also seized by the customs authority at New York harbor. The Report of the Commission on Obscenity and Pornography, 18-19, 94-5, 113.

39. Compare Kutchinsky, Law, Pornography and Crime, 86-7; Arnberg, Motsättningarnas marknad, 151-8.

40. SOU 1969: 38.

41. See for instance, Private no. 1-10; Sexy-Cats no. 3, 1968; Indiscreet med kontakt no. 1, 1968; Gorillan 1968. See also Jonsson, Pressen, reklamen och konkurrensen, 35, in which pornography and comics are described as being of minor importance to the advertising market.

42. For further discussion about the "Swedish sin" and the pornographic press, see Arnberg, "Synd på export."

43. See for example, Homo International Magazine (1966-1969) and Homokontakt (1968). See also Bertilsdotter, "Vi tar farväl"; Lindeqvist, "Större frihet"; Arnberg, Motsättningarnas marknad, ch. 3.

44. Swedish National Archive, Committee Archives, Commission of Inquiry on Freedom of Speech, Kommittén för lagstiftningen om yttrande och tryckfrihet 1965-1969, vol. 8, letter from AB Hsonproduktion October 25 1966; Ibid, vol. 1, supplement no. 2 from the film censorship commission (Filmcensurutredningens bil 2 till prot.) December 16, 1966.

45. Kutchinsky, Law, Pornography and Crime, 92.

46. "Sveriges nyaste exportindustri! Porr för 150 miljoner!" Expressen, September 12, 1967.

47. See annual financial reports for Hsonproduktion for the period, Swedish Companies Registration Office (Bolagsverket), Sundsvall. See also diagram 2.4 in Arnberg, Motsättningarnas marknad.

48. Arnberg, "Hallo boys!"; Lennerhed, Frihet att njuta, ch 11.

49. See SOU 1969: 38 and the Government bill, Prop. 1970: 125.

50. Earlier, magazines like Piff contained some pages directed at a male homosexual audience, with pictures of naked men.

51. Compare Kutchinsky, Law, Pornography and Crime, 104-5; Hebditch and Anning, Porn Gold, 3-5; Arnberg, Motsättningarnas marknad, 280.

52. Hebditch and Anning, Porn Gold, 178; Arnberg, Motsättningarnas marknad, 175-7.

53. SOU 1969: 38, 63.

54. The company was owned by 130 Swedish newspapers and magazines and had the purpose of being an impartial service organ for all Swedish press. See Kugelberg, "Inledning," in Frick, Bergh, and Nilsson, eds., Pressbyrån, 6.

55. SOU 1969: 38, 33.

56. The Advisory Board exemplified the more offensive content as: "provocative and offensive covers, undisguised photographic and cartoon depictions of sexual intercourse and other similar situations, violence and sadism in sexual contexts and personals related to the latter behaviour" (author's own translation from the Swedish, "utmanande och stötande omslagsbilder, ohöljda fotografiska och tecknade framställningar av samlag och samlagsliknande situationer, våld och sadism i sexsammanhang samt kontaktannonser i anslutning till sistnämnda beteenden)." Swedish National Archive, Committee Archives, Commission of Inquiry on Freedom of Speech, Kommittén för lagstiftningen om yttrande och tryckfrihet 1965-1969, vol. 8, Skrivelse till Eira-förlaget, Etno-förlaget, Förlags AB Hansa, AB Hsonproduktion, Kontinentpress AB, Monogram press, Solanco AB, Svea Förlags AB, Svea Press AB och AB Veckotidning från Aktiebolaget Svenska Pressbyrån, October 31, 1968.

57. In 1967, Sextas no. 3 was stopped, in 1968 Helios aktstudier no. 5 and Indiscreet were stopped, and in 1969 Fritidssex no.10 and 11 were stopped. The publishing companies Hsonproduktion and Svea Press received additional warnings in 1968 for the content of Piff, Raff, and Modern Girls. See Swedish National Archive, Committee Archives, Commission of Inquiry on Freedom of Speech, Kommittén för lagstiftningen om yttrande och tryckfrihet 1965-1969, vol. 8, Minutes from meeting with the Advisory Board of the Press at Swedish Media Publishers Association in Stockholm (Protokoll fört vid sammanträde med Pressens Rådgivande Nämnd på Svenska tidningsutgivareföreningen i Stockholm), February 15, 1968, October 2, 1968, December 16, 1968, and March 7, 1969. In 1968, Maxim received a warning and Puss, a radical art magazine, was denied distribution; see Swedish National Archive, Committee Archives, Commission of Inquiry on Freedom of Speech, Kommittén för lagstiftningen om yttrande och tryckfrihet 1965-1969, vol. 8, Minutes from meeting with the Advisory Board of the Press at Swedish Media Publishers Association in Stockholm (Protokoll fört vid sammanträde med Pressens Rådgivande Nämnd på Svenska tidningsutgivareföreningen i Stockholm), October 29, 1968.

58. Compare Report by Parliamentary General Draftment Committee (Allmänna beredningsutskottets utlåtande) no. 2, 1960.

59. "Pornografin," Dagens Nyheter, March 24, 1961.

60. "Pornografien ånyo under debatt," Smålands dagblad, December 12, 1960.

61. Swedish National Archive, Attorney General Archive, main archive, Documents to the General Diary (Handlingar till allmänna diariet), EIIIa, 1961, dnr 43 and 48.

62. "Föga troligt skrivelsen ger resultat: Pressbyrån är skyldig att distribuera," Norrländska socialdemokraten, July 24, 1960.

63. Swedish National Archive, Attorney General Archive, main archive, Documents to the General Diary (Handlingar till allmänna diariet), EIIIa, 1961, dnr 43 and 48.

64. The Ögat publisher later also distributed for example Album Artiste Studiomodeller, Swedish National Archive, Attorney General Archive, main archive, Documents to the General diary (Handlingar till allmänna diariet), EIIIa, 1963, dnr 142.

65. The evening paper Aftonbladet commented that the magazines apparently considered it more important to be close to the limit of possible prosecution than to maintain national distribution. Aftonbladet also claimed that politicians did not foresee this development and called for further combat against the pornographic press. "Två storutgivare dirigerar svenska pornografipressen," Aftonbladet, April 18, 1960.

66. Swedish National Archive, Attorney General Archive, main archive, Press coverage of individual cases (Pressklipp enskilda ärenden), ÖIIb 18, Transcript of letter to the Minister of Justice, dated June 14, 1960, 4.

67. Swedish National Archive, Attorney General Archive, main archive, Documents to the General Diary (Handlingar till allmänna diariet), EIIIa, 1963, dnr 52.

68. Some of the new pornographic magazines thus applied for authority to publish. In 1967, applications peaked when eleven pornographic magazines applied. The same year, however, 65 new pornographic magazines were issued. See Swedish Patent and Registration Office register of periodicals in comparison to Arnberg, Motsättningarnas marknad, Appendix 1.

69. SOU 1969: 38, 33.

70. See also Hebditch and Aninng, Porn Gold, 44, about Berth Milton Senior's own deliveries to kiosks with the first edition of Private magazine.

71. Silbersky and Nordmark, Såra, 66ff.

72. "Och det är ett hot därför att Pressbyrån är det enda specialföretaget för tidningsdistribution, som effektivt och till ett billigt pris kan få ut tidningar till läsekretsen," Pressfönstret, Swedish Television, Channel 1, December 1, 1966.

73. "Pressfönstret," Swedish Television, TV1, December 1, 1966.

74. See Swedish National Archive, Committee Archives, Commission of Inquiry on Freedom of Speech, Kommittén för lagstiftningen om yttrande och tryckfrihet 1965-1969, vol. 1, Protokoll från Kommittén för lagstiftningen om yttrande- och tryckfrihets sammanträde med Pressens rådgivande nämnd den 2 februari 1967.

75. "Porrförsäljare i Malmö: Beslaget ologiskt," Kvällsposten, July 5, 1967; "Justitieministern stoppade 'Orgasm'," Expressen, June 25, 1967; "Hr Kling begär åtal mot utgivare av porr," Svenska Dagbladet, July 4, 1967; "Porr trycks i hemlighet: Kontrollen skärps," Dagens Nyheter, July 4, 1967; "Han porrkrigar med Herman Kling," Aftonbladet, July 8, 1967; "Porrutgivarna angav varann!" Expressen, July 8, 1967; "Uppsalabeslag på 25 exemplar vid porrazzia," Upsala Nya Tidning, July 4, 1967; "Porrbeslag i Karlskrona—Blixtrazzia i tidningsstånden," Blekinge Läns Tidning, July 7, 1967. See also Swedish National Archive, Committee Archives, Commission of Inquiry on Freedom of Speech, Kommittén för lagstiftningen om yttrande och tryckfrihet 1965-1969, vol. 3, Rådhusrättens i Malmö dom den 30 oktober 1967 no 187/1967; Kungl.Maj:ts och rikets hovrätts över Skåne och Blekinge dom den 2 februari 1968, dom no III:33.

76. "Porrförsäljare i Malmö: beslaget ologiskt," Kvällsposten, July 5, 1967.

77. "Porrutgivarna angav varann! Kling: När upplagorna sjönk gick man ännu längre i sadism," Expressen, July 8, 1967.

78. Ibid.

79. "Sanering i porrträsket behövligt...," Norrbottenskuriren, July 5, 1967; "Nu har han härdats: Porrinsamlingen avslutad 150 exemplar beslagtogs," Nerikes allehanda, July 5, 1967.

80. "Han porrkrigar med Herman Kling," Aftonbladet, July 8, 1967.

81. Swedish National Archive, Attorney General Archive, main archive, Documents to the General Diary (Handlingar till allmänna diariet), EIIIa, 1968, no. 294.

82. Swedish National Archive, Attorney General Archive, main archive, Documents to the General Diary (Handlingar till allmänna diariet), EIIIa, 1963, 142.

83. Swedish National Archive, Ministry of Justice Archive, Cabinet Meeting Act to Government Bill 1970:125, Consultation response from Stockholm Municipal Court January 12, 1970; Silbersky and Nordmark, Såra, 22.

84. See Silbersky and Nordmark, Såra, 43.