Does Marital Satisfaction Matter for Dyadic Associations Between Multimorbidity and Subjective Health Among Korean Married Couples in Middle and Later Life?1

The present study aims to investigate how marital satisfaction moderates the dyadic associations between multimorbidity and subjective health. Data were extracted from the Korea Longitudinal Study of Aging in 2016 and 2018. The sample was Korean married couples in middle and later life (N = 780 couples with low marital satisfaction, N = 1,193 couples with high marital satisfaction). The independent variable was multimorbidity, measured by the number of chronic diseases per person. The dependent variables were subjective life expectancy and self-rated health to represent subjective health. Marital satisfaction was a binary moderator, dividing the sample into low and high marital satisfaction groups. We applied the Actor Partner Interdependency Model to examine actor and partner associations simultaneously and used multigroup analysis to test the moderating effects of marital satisfaction. The results showed that husbands' multimorbidity was negatively associated with wives' self-rated health among couples in both the low and high marital satisfaction groups. In couples with high marital satisfaction, wives' multimorbidity was negatively associated with husbands' self-rated health, but this was not true for couples with low marital satisfaction. Regarding actor effects, multimorbidity was associated with self-rated health in both marital satisfaction groups. The actor effect of multimorbidity on the subjective life expectancy was significant only among women with low marital satisfaction. These findings suggest that there are universal and gendered associations between multimorbidity and subjective health in couple relationships.

L'étude examine comment la satisfaction conjugale modère les associations dyadiques entre multimorbidité et santé subjective. Les données provenaient de l'étude longitudinale coréenne sur le vieillissement en 2016/2018. L'échantillon était composé de couples mariés aux stades intermédiaires et ultérieurs de vie (N = 780 couples à satisfaction conjugale faible, N = 1193 couples à satisfaction conjugale élevée). La variable indépendante était la multimorbidité, mesurée par le nombre de maladies chroniques. Les variables dépendantes étaient l'espérance de vie subjective et la santé autoévaluée représentant la santé subjective. La satisfaction conjugale était un modérateur binaire, divisant l'échantillon en groupes de satisfaction conjugale faible et élevée. Nous avons appliqué le modèle d'interdépendance des partenaires acteurs pour examiner simultanément les associations acteurs et partenaires et utilisé une analyse multigroupe pour tester les effets modérateurs de la satisfaction conjugale. Les résultats démontraient que la multimorbidité des maris était négativement associée à l'autoévaluation de la santé des femmes parmi les couples des groupes à satisfaction conjugale faible et élevée. Dans les couples très satisfaits, la multimorbidité des femmes était négativement associée à l'autoévaluation de la santé des maris, ce qui n'était pas le cas pour les couples peu satisfaits. Concernant les effets acteurs, la multimorbidité était associée à l'autoévaluation de la santé dans les deux groupes de satisfaction conjugale. L'effet acteur de la multimorbidité sur l'espérance de vie subjective était significatif uniquement chez les femmes à satisfaction conjugale faible. Ces résultats suggèrent l'existence d'associations universelles et genrées entre multimorbidité et santé subjective dans les relations de couple.

marital satisfaction, multimorbidity, subjective health, self-rated health, subjective life expectancy, Korean middle-aged and older couples

satisfaction conjugale, multimorbidité, santé subjective, santé autoévaluée, espérance de vie subjective, couples coréens d'âge moyen et plus âgés

[End Page 508]

Introduction

South Korea (hereafter "Korea") is becoming a "centenarian" society, where most people die of natural causes at age 90 or older. Because of this, Korean society has the fastest-increasing proportion of older people in the world (OECD, 2019). People tend to develop one or more chronic diseases after middle age. As a result, longevity, along with diseases, has become common in Korea's aging population (Kim and Kim, 2019). In Korea, the number of elderly people with multimorbidity, meaning the simultaneous presence of two or more chronic diseases, after middle life is growing significantly (Mercer et al., 2016). In this vein, people usually begin to worry about their health in their middle age as their physical function deteriorate (Colombo et al., 2020).

In previous research on multimorbidity, the negative effects of multimorbidity on the following variables have been shown in middle and later life: quality of life (Singh et al., 2017), subjective life expectancy (Kobayashi et al., 2017), cognitive function (Ge et al., 2018), and active aging (Maresova et al., 2019). By contrast with research dealing with objective measure on health such as mortality (Buja et al., 2020), subjective perceptions of health, such as self-rated health or subjective life expectancy, have paid attention to comprehensive predictors of health (Kim and Kim, 2017). This is because subjective factors are more likely to reflect respondents' way of life, family disease history, socio-economic status, practical behaviors for healing, and cultural characteristics (Kim and Kim, 2019).

Meanwhile, the proportion of the coupled households that includes only one couple has increased among those 45 years old and older in Korea, from 4.0% in 2000 to 7.5% in 2020 (Choi et al., 2020; Statistics Korea, 2020). In this context, couples support their partners in cases of multimorbidity, which is necessary [End Page 509] to establish long-term care. In fact, in 2017, it was reported that approximately 80% of older people obtain or give care within their couple relationships, with over 85% providing emotional support and over 75% instrumental support (Jung et al., 2017). As a result, the salience of couples' interaction has gained importance in couple-based living. In relation to the life course system perspective, which integrates the life course and the system perspectives (Wickrama and O'Neal, 2020), couples in middle age or older show more closely interrelated health issues, supporting the concept of increasingly linked lives.

According to the theory of interdependence (Kelly et al., 2003; Rusbult and Van Lange, 2003) and the life course system perspective (Wickrama and O'Neal, 2020), interdependence within couples has attracted greater attention as an important issue in subjective health. Couples' perceived health has a strong tendency to interact with the levels of couple relationships, for instance. In particular, the quality of a couple's relationship plays a salient role in health in terms of the concept of marital strength (Slatcher, 2010). This is because couples with higher levels of satisfaction in their relationships are most likely to be supportive of each other, as well as reporting a sense of stability based on affection, particularly in relation to health crises (Liu, 2012; Proulx and Snyder-Rivas, 2013).

Despite the salience of subjective aspects in health-related factors and the interdependencies within couples, previous studies have tended to focus on the association between multimorbidity and objective health and psychological outcomes (Ge et al., 2018; Kobayashi et al., 2017). Also, previous studies have usually adopted an individualized approach rather than a relational approach one. However, the quality of the marital relationship exerts a strong influence on the subjective perception of health and the experience of multimorbidity (Kim and Kim, 2017) within the growing salience of couplecentered lives in middle age and later life in contemporary Korea (Nam and Kim, 2014). Therefore, this study examined couples' interdependence associations between multimorbidity and subjective health with the moderating effects of marital satisfaction.

Literature Review

Subjective Health in Middle and Later Life

Middle age is defined as the period of life between the youth and old age, usually referring to the period between forty and sixty-five (Geldsetzer et al., 2019). However, as longevity increases, the age range for middle age has been pushed back to forty-five in more recent research (Colombo et al., 2020). Older age is typically defined as sixty-five years and older (Maresova et al., 2019). Due to the aging process and the modern trend toward sedentary lifestyles and poor eating habits, middle and older age are generally the most vulnerable periods for chronic health risks (Ge et al., 2018). Thus, middle-aged and older people are more likely to be concerned about their health than younger people (Quiñones et al., 2019). [End Page 510]

Due to the potential for longer lives and thus longer battles with disease, middle-aged and older people with multiple chronic conditions are becoming more dependent on caregivers' help for long-term care (Ge et al., 2018). In contemporary society, the partner of someone with a chronic illness tends to play the role of caregiver because of the increasing number of coupled households, especially in Korea (Jung et al., 2017). In general, however, the context of caregiving is heavily gendered for multiple chronic conditions. In the United States, about 70% women in middle age and later life are involved in long-term care-giving within their families (Body, 2020), and the phenomenon is much more common in Korea, due to the persistence of the patriarchy (Jang and Yang, 2019). Caregiving within a coupled relationship depends on connectedness and crossover within the relationship. According to the life course and system perspective (Wickrama and O'Neal, 2020), a partner's illness can have a significant influence on caregivers' perception of their subjective health.

Subjective health is the evaluation of one's own health (Toothman and Barrett, 2011). It is sometimes measured with a single questionnaire item, such as 'In general, would you say your health …' (Bomback, 2013). Previous studies of subjective health are most likely to use self-rated health as the operational variable (Araújo et al., 2018). This is because that variable has concrete reliability for prediction of the deterioration of physical ability or for measurement of physical health (Ayalon et al., 2014). In fact, the measure of "self-rated health" is used worldwide as a reliable measure in health-related research (Pinilla-Roncancio et al., 2020).

Another variable that is growing in importance of subjective health is subjective life expectancy. This term is defined as whether people expect to be able to live another 10–15 years (Kobayashi et al., 2017). Research using the US Health and Retirement Study data have indicated that subjective life expectancy has a great deal of utility in the prediction of actual mortality in middle and later age (Hurd and McGarry, 2002; Smith et al., 2001). Because subjective life expectancy predicts the period of life remaining, it influences health-related activities, such as taking up healthy eating habits or exercising, which require active agency and a sense of control (Kim and Kim, 2017; Lee et al., 2017).

Ample evidence exists indicating that socio-demographic factors are closely linked to subjective health, including subjective life expectancy and self-rated health. Younger age, higher household income, and higher educational attainment were associated with better subjective health (Bell et al., 2020; Chaparro et al., 2019; Kobayashi et al., 2017). Health-related factors were also connected to subjective health, including smoking status, depressive symptoms, cognitive function, activities of daily living (ADL), and hospitalization (An, 2018; Rappange et al., 2015). Smokers and those who have been hospitalized are more likely to report lower levels of subjective health (Scott-Sheldon et al., 2010). Higher levels of depressive symptoms are tied to negative perceptions of subjective health (An, 2018; Mirowsky and Ross, 2000). Better cognitive function has a positive influence on subjective health, especially subjective life expectancy (Bardo and Lynch, 2019). [End Page 511]

Association Between Multimorbidity and Subjective Health

Despite the limited extent of study on subjective life expectancy, multimorbidity could be a robust predictor for establishing people's thresholds for the end of life (Kim and Kim, 2019). In other words, people with multimorbidity are more likely to predict their death to be soon (Ayalon et al., 2014). In detail, the association between multimorbidity and the deterioration of physical function has been proven (Zaninotto and Steptoe, 2019). Lower levels of physical function by multimorbidity can lead individuals to feel that their physical condition has deteriorated compared to the past. As a result, people with multimorbidity are more likely to report lower levels of subjective life expectancy (Maresova et al., 2019).

There have been a few studies on the association between multimorbidity and subjective health. Ge et al., (2018) found a significant association between chronic diseases and self-rated health. They also pointed out that the impacts of age on the number of chronic diseases and subjective health could be significant for middle-aged and older adults. Research on self-rated health has shown that morbidity in chronic diseases can trigger lower levels of psychological or physical conditions (Colombo et al., 2020). That is, multimorbidity leads to an increase in the frequency of hospital admission due to the need to manage diseases as well as the regularity of medicine-taking (Buja et al., 2020). This leads to a tendency to raise the patient's awareness of the disease, and consequently, it leads to lower levels of subjective well-being (Zaninotto and Steptoe, 2019). Hence, it could be said that multimorbidity is most likely to contribute to poor self-rated health (Ocampo-Chaparro, 2010). On the other hand, Mirowsky and Ross (2000) concluded that there is no significant association between the number of chronic diseases suffered and one's subjective life expectancy. They explained that one of the reasons for this is that multimorbidity and self-rated health have a strong significant association, such that the power of the association between multimorbidity and subjective life expectancy can be blurred.

Despite the lack of a conceptual framework, both self-rated health and subjective life expectancy belong to subjective health as a kind of personal evaluation of health (Toothman and Barrett, 2011). There are, however, slight differences between two variables. Self-rated health focuses on illness or health-related behaviors such as exercising, while subjective life expectancy is more likely to relate to family health history or one's present health situation, involving speculation on the future lifestyle. Self-rated health may exhibit a narrower perspective on health than subjective life expectancy (Lee et al., 2020). Thus, the two variables should be distinguished, although both are indicators for subjective health.

Interdependence in Couples and Moderating Effects of Marital Satisfaction on the Association Between Multimorbidity and Subjective Health

Interdependence theory (Kelly et al., 2003; Rusbult and Van Lange, 2003) indicates a strong interconnectedness with one's partner (Ayalon et al., 2014). The theory suggests that couples' interactions cross over between themselves and their [End Page 512] partners (Rusbult and Van Lange, 2003). Regarding coupled interdependency in aging, a life course system perspective also indicates couples experience health processes together in their longitudinal life course and the coupled relationship. The perspective of the life course system has shown an integration of both the life course perspective and the system perspective by Wickrama and O'Neal (2020). This perspective has asserted the salience of the impacts of long-term coupled relationship patterns on couples' health. This is because the accumulated coupled dynamics and levels of relational satisfaction are closely tied to their health in the name of linked lives. Here, intra-individual associations state individuals' aging processes as an actor effect, while individuals' characteristics are associated with partners' characteristics within couples in what is termed a "partner effect" (Stowe and Cooney, 2015; Wickrama et al., 2020).

The existence of a partner is considered a protective factor for subjective health, especially in the "empty nest" period (after grown children leave home) through to middle and later life (Gardner and Oswald, 2004). As multimorbidity tends to gradually require a caregiver, family support acts as a mitigator for fatalistic subjective health (Pinilla-Roncancio et al., 2020). In the earlier literature, the consequences on feasibility of having a partner have been widely shown, as the partner can play a supportive role for people with chronic diseases (Liu, 2012). For instance, those who live with multimorbidity tend to feel emotional distress, and the presence of a partner is more likely to mitigate the negative association between multimorbidity and subjective health (Croezen et al., 2012).

Nevertheless, scholars have indicated that the association between multi-morbidity and subjective life expectancy or self-rated health depends on the quality of marital satisfaction. This is because positive interactions in the relationship with one's partner or its high quality are a resource for the context of an illness (Slatcher and Schoebi, 2017). At the same time, dyadic satisfaction has a direct influence on subjective health, including the deterioration of physical well-being (Kimmel et al., 2000). Overall, research focusing on marital quality shows the consensus conclusion that couples who are satisfied in their marital relationships show better health conditions (Robles et al., 2014). In a coupled system, people are intercorrelated with their partners' health perception, as satisfied couples in their relationships are more likely to care and give emotional and instrumental support to each other, compared to single individuals or couples who have poor marital satisfaction (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2008; Proulx et al., 2007).

However, heterosexual marital relationships are gendered. Generally, women are more likely to depend on the quality of marital satisfaction than men, due to women's emotional vulnerability and greater interpersonal needs (Gardner and Oswald, 2004; Proulx and Snyder-Rivas, 2013). Traditionally, there are clear gender role expectations in Korean society: women are responsible for housework and are subordinate to their husbands, while men perform the duties of breadwinner, although women's participation in the workplace has increased, slowly leading to an increasing perception of gender equality (Yang, 2018). [End Page 513]

The Analytic Model

As a result, women have the tendency to belong to their partners, making them more likely to depend on the quality of their marital relationships, for instance. Having said that, higher levels of marital satisfaction operate as a moderator. Namely, satisfying marital relationships act as a buffer, protecting subjective health in multiple chronic conditions (Slatcher, 2010). Having a satisfying relationship with one's partners strengthens interconnectedness among couples by having emotional or instrumental exchanges on a daily basis (Slatcher and Schoebi, 2017). Thus, the moderating effects of marital satisfaction have an influence on the association between multimorbidity and subjective health for both wives and husbands.

Using the life course system perspective and marital strength concept, the present study examined the moderating effects of marital satisfaction on the interdependent associations between multimorbidity and subjective health. Figure 1 shows an analytic model of two groups with high and low marital satisfaction.

In relation to the previous literature, the following hypotheses were set:

1. Husbands' and wives' multimorbidity is associated with not only their own subjective health (actor effect) but also their partners' subjective health (partner effect), measured as subjective life expectancy and self-rated health.

2. Marital satisfaction moderates the association between multimorbidity and subjective health, including subjective life expectancy and self-rated health.

Method

Data

We used the sixth and seventh wave of the Korea Longitudinal Study of Aging (KLoSA) collected by the Korea Employment Information Service in 2016 and in 2018. The KLoSA has been conducted biennially since 2006, using a stratified [End Page 514] systematic sampling method. The sampling frame is that of the 2005 Korean Population and Housing Census. The original sample for the first wave was 10,254 randomly selected respondents aged 45 years or older (born before 1961) and residing nationwide with the exclusion of Jeju Island in 2006. The original sample retention rate of the existing panel was stable at 77.6% until the seventh follow-up survey. New panels were added in the fifth wave (in 2014), with three surveys have been conducted so far, and the sample retention rate is 89.4%. A total of 6,940 individuals participated in the seventh KLoSA survey, including both the existing panel since 2006 and a new panel since 2014. We selected the sample using these criteria: 1) both partners participated in the KLoSA sixth and seventh survey (N = 5,129, 73.69%) and have remained in their marriage, including cohabitation, and 2) there are no missing values for chronic disease, subjective life expectancy, self-rated health, marital satisfaction or covariates (N = 1,973, 28.35%). We divided the participants into two groups, high marital satisfaction and low marital satisfaction, according to the mean of marital satisfaction for the sixth wave of KLoSA.

The final sample was couples in middle and later life with low (N = 780) and high (N = 1,193) marital satisfaction. The descriptive characteristics of the present sample are shown in Table 1. Their age range was 55 to 95 years. KLoSA began with 45-year-olds in its first wave and traced them for a decade until the sixth wave. Consequently, the youngest age of the sixth wave was 55 years old. The mean age of husbands with low marital satisfaction was 71.08 (SD = 8.89), and the mean age of wives with low marital satisfaction was 67.28 (SD = 8.25). The mean age of husbands with high marital satisfaction was 68.60 (SD = 8.54), and the mean age of wives with high marital satisfaction was 65.27 (SD = 7.85). Over 50% of husbands in the low marital satisfaction group and in the high marital satisfaction group had completed high school or higher. However, about 35% of wives in the low marital satisfaction group and about 48% of wives in high marital satisfaction group had completed high school or higher.

Measures

Subjective life expectancy and self-rated health

The dependent variables were subjective life expectancy and self-rated health to indicate subjective health. These variables were measured at the seventh wave of KLoSA. Subjective life expectancy referred to the subjective perception of the possibility of survival after 10 to 15 years. Participants responded using a Likert scale from 0 to 100 at intervals of ten. Scores closer to 0 meant that the participant perceived little chance of survival, and scores closer to 100 meant that they perceived the probability of survival to be very high. The mean levels of subjective life expectancy were 51.97 (SD = 24.25) for husbands with low marital satisfaction, 53.39 (SD = 24.05) for wives with low marital satisfaction, 62.57 (SD = 23.02) for husbands with high marital satisfaction and 63.12 (SD = 21.74) for wives with high marital satisfaction. Self-rated health was measured with the single item "What do you think about your general health?" and the participants gave responses on a Likert scale from 1 to 5. [End Page 515]

Descriptive Characteristics of Participants

Higher scores indicated better subjective health. The mean values for self-rated health were 2.91 (SD = 0.83) for husbands with low marital satisfaction, 2.94 (SD = 0.92) for wives with low marital satisfaction, 3.19 (SD = 0.80) for husbands with high marital satisfaction, and 3.17 (SD = 0.79) for wives with high marital satisfaction, as shown in Table 1.

Multimorbidity

The independent variable was multimorbidity, measured in terms of the number of chronic diseases in the sixth wave of KLoSA. We used eight questions about chronic diseases, including hypertension, diabetes, cancer, chronic lung disease, liver disease, heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, and arthritis or rheumatoid arthritis (1 = diagnosed; 0 = no). If past diagnosed chronic diseases before the sixth wave survey had not been cured, they were incorporated into the total number of chronic diseases at the sixth wave (1 = with; 0 = without). Then we summed all items for chronic disease to generate the variable for multimorbidity. The conceptual range of multimorbidity was from 0 to 8. Higher scores meant more chronic diseases. The mean scores of multimorbidity were 1.03 (SD = 1.08) for husbands with low marital satisfaction, 1.16 (SD = 1.13) for wives with low marital satisfaction, 0.88 (SD = 0.99) for husbands with high marital satisfaction, [End Page 517] and 0.84 (SD = 0.98) for wives with high marital satisfaction. Those who had more than one chronic disease were 467 (59.9%) husbands and 509 (65.3%) wives in the lower marital satisfaction group, along with 648 (54.3%) husbands with 648 (54.3%) wives in the higher marital satisfaction group, as seen in Table 1.

Marital Satisfaction

The moderating variable of marital satisfaction was measured in the sixth wave of KLoSA with a single question: "Are you satisfied in your relationship?" Participants responded on a Likert scale from 0 to 100, in increments of 10. Higher scores meant greater marital satisfaction. We divided respondents into two groups according to the grand mean value of couple-level marital satisfaction (M = 69.15, SD = 12.55), which was calculated by the mean between wives' and husbands' marital satisfaction at the sixth wave. The mean scores for marital satisfaction as seen in Table 1 were 58.38 (SD = 11.76) for husbands with low marital satisfaction, 55.19 (SD = 11.54) for wives with low marital satisfaction, 77.87 (SD = 8.39) for husbands with high marital satisfaction, and 76.59 (SD = 8.25) for wives with high marital satisfaction.

Covariates

The covariates were age, household income, working status, education level, smoking, depressive symptoms, cognitive function, ADL, and hospitalization. All of covariates were taken from the seventh wave of the KLoSA. Household income was calculated with the mean of the husbands and wives. Higher values indicated the higher household incomes per year. Working status was coded with two categories (0 = not working; 1 = working). Education level indicated the highest level of school completed (1 = uneducated or elementary; 2 = middle school; 3 = high school; 4 = college or more). Smoking was measured as a binary variable (0 = never smoker or previous smoker but quit; 1 = current smoker). Depressive symptoms were measured using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10). It consisted of 10 items that indicated how frequently people had experienced depressive symptoms over the previous week. We summed all items for depressive symptoms across the range of 10 to 40. Higher scores indicated feeling frequent depressive symptoms. Cronbach's alpha values for depressive symptoms were 0.88 for husbands with low marital satisfaction, 0.88 for wives with low marital satisfaction, 0.86 for husbands with high marital satisfaction, and 0.86 for wives with high marital satisfaction. Cognitive function was measure with the Korean version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE). It contained orientation for time and place, recall, language, registration, attention, calculation, and visual construction. The range was 0 to 30, and higher values meant better cognitive function. ADL was calculated by summing seven activities (e.g., taking a shower or eating meals) with a binary code (0 = doing independently; 1 = with help). The total score for ADL was in the range 0 to 7, with higher scores indicating more help needed for ADL. Hospitalization was a binary variable (0 = not hospitalized in the past two years; 1 = hospitalized in the past two years).

Analysis

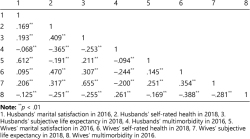

There were three analytic steps in the present study. First, we performed descriptive analysis to show the general characteristics of couples in this study (Table 1). [End Page 518] Second, we performed Pearson's correlation analysis for the study variables (Table 2). Third, we applied the Actor Partner Interdependence Model (APIM; Kenny et al., 2006) to examine actor and partner associations simultaneously, as well as a multigroup analysis to test the moderating effects of marital satisfaction. The APIM has the advantage of allowing actor and partner effects to be estimated at the same time. Actor effects here indicate that the individual's factors have effects on individual own outcomes. Partner effects indicate that the individual's factors have effects on their partner's outcomes. Moreover, multigroup analysis helps researchers analyze two or more groups simultaneously and compare several estimated statistics. Thus, we analyzed the model comparison between the low marital satisfaction group and the high marital satisfaction group or between two paths within the model as the final step of analysis. We ran a constrained model with two constrained coefficients that we wished to compare after analyzing the baseline model with all freely estimated coefficients. Then, we calculated a chi difference test between the constrained model and the baseline model. If the results of the chi difference test are significant, the two coefficients that were constrained in the model were not the same. We used Mplus with the structural equation modelling (SEM) approach and the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation (Version 7.4; Muthén and Muthén, 2017). To evaluate the model fit with the data in the SEM approach, the chi-square statistic, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and the standardized root mean residual (SRMR) were adopted based on Hu and Bentler (1999), who suggested that values of RMSEA under 0.06, of CFI and TLI over 0.95, and of SRMR under 0.06 indicated the appropriate model. The multigroup APIM analytic model is appropriate for the present dataset, and all model fit indexes were acceptable (χ2 (64) = 113.64, p = 0.000; CFI = 0.987; TLI = 0.967; RMSEA = 0.028, CI (0.019, 0.036); SRMR = 0.010).

Results

Interdependence Between Chronic Diseases and Subjective Health in Those with Low Marital Satisfaction

We conducted APIM for couples with low levels of marital satisfaction to examine the actor and partner effects of multimorbidity on subjective health (subjective life expectancy and self-rated health) among couples with low marital satisfaction. Table 3 and Figure 2 showed the APIM results in the low marital satisfaction group. In terms of actor effects, wives' multimorbidity had negative associations with wives' subjective life expectancy (b = -1.753, p < . 05) and self-rated health (b = -0.155, p < .001). Husbands' multimorbidity was also negatively associated with husbands' self-rated health (b = -0.123, p < .001). However, the association between husbands' multimorbidity and their own subjective life expectancy was not significant. Regarding partner effects, the association between husbands' multimorbidity and wives' self-rated health was the only significant association (b = -0.075, p < . 01). Husbands with more chronic diseases had wives who reported lower self-rated health. All cross-correlations between the spouses in the model [End Page 519]

Results of Pearson's Correlation Coefficient of Study Variables (N = 1,973)

were significant. In particular, the husbands and wives showed inter-correlations in subjective life expectancy and self-rated health. Additionally, the correlations between subjective life expectancy and self-rated health were significant among both husbands and wives with low marital satisfaction.

Interdependence Between Chronic Diseases and Subjective Health in Those with High Marital Satisfaction

Table 4 and Figure 3 show the APIM results for actor and partner effects of multimorbidity on subjective health (subjective life expectancy and self-rated health) in couples with high marital satisfaction. The multimorbidity of wives had a negative association with their own self-rated health (b = -0.145, p < .001), but this did not have a significant association with their own subjective life expectancy. Husbands also showed the same patterns as their wives. The multimorbidity of husbands had a significant negative association with their own self-rated health (b = -0.145, p < .001), but this was not found with their own subjective life expectancy. In terms of partner effects among couples with high marital satisfaction, the association between husbands' multimorbidity and wives' self-rated health was significant (b = -0.049, p < .05), as was this result for couples with low marital satisfaction. If husbands had more chronic diseases, wives self-rated their health as lower. Additionally, the multimorbidity of wives had a significant partner effect on their husbands' self-rated health (b = -0.048, p < .05). If wives had more chronic diseases, husbands reported lower self-rated health, although this association was not present among couples with low marital satisfaction. All cross-correlations between the two spouses in the model were also significant, as was also true for the results for couples with low marital satisfaction. [End Page 520]

Results of the APIM Analyses in Low Marital Satisfaction Group

Results from the Model Constrained for Comparison Between Significant Paths

There were two results in relation to the significance criteria between low marital satisfaction couples and high marital satisfaction couples. The path from wives' multimorbidity to their subjective life expectancy as an actor effect was only significant among couples with low marital satisfaction. Additionally, the path from wives' multimorbidity to husbands' self-rated health as a partner effect was only significant in couples with high marital satisfaction. With the exception of these two paths, the results for actor and partner effects between the spouses had the same level of statistical significance. However, there was more room to compare the strength of associations. Thus, we compared the size of significant associations using model constrained techniques.

Table 5 presents the results from the constrained model. First, we conducted between-group comparisons with two actor effects and one partner effect, all of which were significant at the same time among couples with low marital satisfaction and those with high marital satisfaction: 1) husbands' multimorbidity → husbands' self-rated health (actor effect), 2) wives' multimorbidity → wives' self-rated health (actor effect), 3) husbands' multimorbidity → wives' self-rated health (partner effect). However, the sizes of coefficients among these three paths were not statistically different between the two groups.

In addition, we performed within-group comparisons to establish the gender differences with significant actor and partner effects. In the low marital satisfaction group, we analyzed one comparison between wives' actor effect from multimorbidity to self-rated health and husbands' actor effect for the same path as their wives. However, the difference in this actor effect between wives and husbands was not statistically significant. In the high marital satisfaction group, there were two comparisons. [End Page 521]

Results of the APIM Analyses in Low Marital Satisfaction Group (N = 780)

[End Page 523]

Results of the APIM Analyses in High Marital Satisfaction Group (N = 1,193)

[End Page 525]

Results of the APIM Analyses in High Marital Satisfaction Group

Results of the Model Constrain with Multiple Group Analysis

[End Page 526] One was the comparison of the actor effect from multimorbidity to self-rated health between wives and husbands. The other was the comparison of the partner effects of multimorbidity on self-rated health between the two partners. Neither comparison was statistically significant. Thus, there were no gender differences in the within-group comparisons.

Discussion

The purpose of the study was to examine the moderating effects of marital satisfaction on the dyadic associations between multimorbidity and subjective health among Korean couples in middle and later life. To do that, we used APIM with multigroup analysis. The major findings and discussions were follows. First, the actor effects of multimorbidity on self-rated health were significant, regardless of gender or marital quality. This showed that having more chronic diseases made people evaluate their own health condition negatively. This demonstrates that the association between multimorbidity and self-rated health has a powerful connection, more so than subjective life expectancy. It was consistent with the previous research that reported a negative association between multimorbidity and self-rated health (Ocampo-Chapparro, 2010). One reason here could be found in the frequency of hospital admissions, as people in middle and later life with multimorbidity tend to need medical care more often. This type of lifestyle seemed to entail lower levels of self-rated health (Buja et al., 2020; Zaninotto and Steptoe, 2019).

Second, the actor effects of multimorbidity on subjective life expectancy are different from those on self-rated health. The association between multimorbidity and subjective life expectancy was less robust than the association between multimorbidity and self-rated health (Lee et al., 2020; Pinilla-Roncancio et al., 2020). This result implied the power of the association between multimorbidity and subjective life expectancy may be blurred because of the power of self-rated health (Mirowsky and Ross, 2000). It has also been suggested that self-rated health and subjective life expectancy have distinctive natures and different mechanisms related to chronic diseases, even though they share common concepts as subjective health. Self-rated health regards present health or behavior embedded in a comparison with socio-cultural aspects or neighbors (Adjei et al., 2017). On the other hand, subjective life expectancy involves speculation in the subsequent 5 to 10 years based on hope or willingness, and considerations of family health history or current health situation (Lee et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2020). For this reason, different effects might be found on subjective life expectancy and on self-rated health.

It was also possible that the association between multimorbidity and subjective life expectancy varies depending on various contexts because it exhibits a wider perspective on health than self-rated health (Lee et al., 2020). For example, multi-morbidity could influence on their predictions of age at death both positively and negatively (van Solinge and Henkens, 2018). Specifically, if people make enough effort to manage chronic diseases, it can positively influence subjective life expectancy through the perception that the disease is well managed. On the other hand, if the chronic disease itself is recognized as a negative event, it can act as a negative [End Page 527] factor and one may accept death more readily. Currently, the discussion comparing self-rated health and subjective life expectancy is in its very early stages in the academic world (Lee et al., 2020). Further study on the link between chronic diseases and subjective life expectancy is required with focusing on the various mechanisms in a variety of circumstances (Kim and Kim, 2017; Kobayashi et al., 2017).

It also inferred that the association between multimorbidity and subjective life expectancy seemed to be context-specific, such as by gender and marital relationships, rather than universal. Indeed, the results of this study revealed the actor effect of multimorbidity on subjective life expectancy was significant only for women with low marital satisfaction. Women with relatively low marital satisfaction were more likely to focus on not only their partner's health but also their own lives, with greater concerns about their own health after middle and old age in particular (Gardner and Oswald, 2004). Thus, wives with low marital satisfaction could consider their health care and subjective life expectancy with individual-centered preparation for long-term health, rather depending on their partner, compared to those with high marital satisfaction.

Third, the significant intercorrelations between husbands and wives in self-rated health and subjective life expectancy supported the interdependence of subjective health within coupled relationships in middle age and later life. After middle age, lifestyles turn toward couple-based lives because of retirement and grown children's independence. As a result, health-related behaviors are most likely to be shared among couples. The life course system perspective, moreover, underpins the result that accumulated shared lives within couples influence their aging process and their health (Wickrama and O'Neal, 2020). A number of studies dealing with couples' concordance or interdependence have found a vigorous correlation between the subjective health of partners within a couple because of their shared lifestyle or assortative mating, as well as common stressors (Jackson et al., 2015; Leong et al., 2014). This implies the need for a couple-framed subjective health approach rather than an individual-based one for middle age and later life.

Fourth, there were no statistical differences from marital quality in the results for actor effects between multimorbidity and self-rated health and that of the associations between husbands' multimorbidity and wives' self-rated health. In detail, the experience of multimorbidity could lead middle-aged or older people to think about their life expectancy or to consider their self-rated health. Those with multiple chronic conditions might focus on the individual experience of illness itself rather than depending on the quality of marital satisfaction. Furthermore, due to the circumstance of women's intensive caregiving in Korea, wives are more likely to care for and monitor their multimorbid partners on a daily basis, regardless the quality of marital satisfaction (Jang and Yang, 2019). This situation could support the result that there are no statistical differences in the association between husbands' multi-morbidity and wives' self-rated health between two different marital quality groups.

Finally, regarding the partner effects among high marital satisfaction couples, the present study showed gender-equalized associations in that the two partner effects of multimorbidity on self-rated health, from wives to husbands and from husbands to wives, were significant with the same strength. In other [End Page 528] words, husbands' and wives' multimorbidity was associated with lower levels of their partners' self-rated health in the high marital satisfaction group, while only husbands' multimorbidity was associated with the lower levels of wives' self-rated health in lower marital satisfaction. This suggests that couples who are satisfied in their relationships are more likely to support and care for each other instrumentally and emotionally (Proulx et al., 2007). They focus on their partners with a sense of affection regarding their illnesses (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2008). In fact, daily emotional or instrumental exchanges in greatly satisfied marital relationships could lead to interconnectedness and crossover between multiple chronic conditions and their partners' self-rated health (Slatcher and Schoebi, 2017), and as a result, partner effects are highlighted in couples with higher marital satisfaction.

We also found gendered partner effects of multimorbidity on self-rated health among couples with lower marital satisfaction. It has been shown that wives report lower self-rated health when husbands have more chronic diseases. It suggested coupled relationships in middle age and later life have a gendered character based on the social functionalism of Korean society. This is because the caregiving role is still obviously gendered; there is no doubt that women play the caring role in supporting ailing family members (Kim and Hui, 2019). A woman whose husband has multimorbidity, therefore, has a great deal of responsibility to support her partner even though their marital relationship is not intimate, which leads her to have lower levels of self-rated health (Ayalon et al., 2014).

The present study has several limitations stemming from its use of panel data and from its research design. One drawback is how this study targets a certain age range. In fact, middle and older age are dealt with as one unit in this paper, so in future research it would be worthwhile to subdivide the age groups with the paradigm of age diversity. This is due to the fact that older people can also be characterized by several age groups (Kim and Kim, 2019). In addition, the middle and older age could have certain differences in terms of their subjective health. Second, future studies could adopt more diverse samples, such as in marital status and marital period as well as marital satisfaction. Marital duration might be an influential factor for marital satisfaction empirically (Whiteman et al., 2007) and theoretically (e.g., life course system perspective; Wickrama and O'Neal, 2020), although KLoSA did not include this. Last but not least, to understand the context of the couples, it would be advisable to combine the use of qualitative and quantitative methods. In this way, a future study could gain sufficient depth to understand the mechanisms relating to a couple's relationship to health in middle age and later life.

In spite of these limitations, it seems clear that interdependency with partners is salient for the association between multimorbidity and subjective health, as chronic diseases are closely linked to long-term daily management within a couple's daily interactions during the entire aging processes (Ayalon et al., 2014). Furthermore, in a similar vein to previous research (Body, 2020; Jang and Yang, 2019), the impact of traditional gender role expectations could be investigated in terms of its presence in middle age and later life, in illness contexts and in the couple relationships. Nonetheless, improvement in the degree of marital quality [End Page 529] could allow couples in middle age and later life to take more gender-balanced roles in their lives related to health maintenance.

Policy Implications

Based on the results of the study, family policymakers could consider couples' interdependency in relation to objective health and subjective health to individual's health improvement. Currently, most health programs are designed for individuals; however, according to the results of this study, an approach based on the interdependence of couples is required rather than individualized programs. As chronic illnesses are likely to be managed at the couple level in daily lives, each other's illnesses affect partners. Thus, it is necessary to help middle-aged couples recognize and prepare for not only the impact their illness will have on their lives but also how their illness affects their spouse. When a chronic disease is experienced between couples, it affects the spouse in different ways depending on gender and quality of the relationship. Therefore, information on the effect of the disease, gendered care norms, or the quality of the marital relationship as salient contexts is important and is necessary to be informed to the elderly couples.

Conclusion

The present study showed that multimorbidity has effects on not only individual's own subjective health but also on their partner's. Marital satisfaction and gender are salient factors on the interdependent associations between multimorbidity and subjective health. Especially, the gendered influence of chronic illnesses among couples with higher relationship satisfaction may differ from one among couples with low relationship satisfaction. It implies that policymakers and field practitioners are in need to consider the couple-based approaches in aging with multimorbidity issues.

Notes

1. This paper is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Hey Jung Jun. She was a leading scholar of innovative studies and a wonderful mentor to many students in the field of successful aging and family relationships. She had been an enthusiastic researcher until the last moments of her life, including her contribution in this study. This paper builds on Dr. Jun's passion for family gerontology and her humble but insightful intellectual guidance.

Acknowledgements This is how you tag ack within a footnote