What's Race Got to Do with It?Exploring the In-Race Adoption of Asian Children

This study sought to explore adoption in Asian American families. There has been much discussion and sometimes heated debate about outcomes for children of color placed transracially and the ability of parents to address adoptees' racial or ethnic socialization needs. Asian children come to U.S. adoptive families largely through intercountry adoption and their foreignness has been situated as a matter of culture rather than race both in practice and in the literature. A small sample of 68 families, where at least one parent is of Asian American descent, provided some preliminary insight into parental motivations and perspectives about adopting Asian children. The majority of the adoptive parents were Chinese American, and the children from China. The primary motivation for adopting was infertility, and similarity or "fit" led the parents to adopt Asian children. The parents overwhelmingly believed that having at least one Asian American parent would be easier for the children, referencing themes of acceptance, fit, and identity congruency. Implicit was their belief that racial and/or ethnic socialization strategies were less intentional and more "natural" than for white adoptive families. While the findings cannot be interpreted as conclusive or representative, overall respondents reported race and ethnicity to be salient to their adoptive decisions and strategies for developing their children's identities.

INTRODUCTION

Research that captures the experiences of Asian Americans parents who have adopted Asian children is scant. Jacobson (2008) notably examined the role of "culture keeping" for parents who have adopted children from Russia and China. Dorow (2006) and Louie (2015) have also comparatively examined perspectives of Chinese American parents of Chinese adoptive children. This exploratory study, although limited methodologically, seeks to contribute to the literature by adding the voices of a broader subsection of families, Asian American parents who have adopted Asian children that include Chinese and/or other Asian ethnicities. The experiences of these families may serve as an impetus for further research to explore the motivations of Asian American adoptive parents and racial and ethnic socialization strategies for children who share Asian American heritage with at least one adoptive parent. The study was constructed in two phases; data was collected in Phase I through surveys, while Phase II involved in-depth interviews. This paper reports the findings from Phase I.

PARENTAL MOTIVATIONS IN INTERCOUNTRY ADOPTION

Bergquist, Campbell, and Unrau (2003) examined the motivations of White adoptive parents in choosing intercountry adoption. They found that parents cited shorter wait times and a general desire to adopt internationally as the two primary reasons for adopting a Korean child, and not any specific interest in Korea. While the White adoptive parents acknowledged their children's racial distinctiveness, the majority did not believe their children identified as Asian American or Korean American. Zhang and Lee (2011) examined the motivations of parents who adopted transracially in the U.S. versus those who chose ICA. Five of the six families with foreign-born children adopted from China and Korea, one family adopted from Russia. The parents who chose ICA were more likely to cite altruistic motivations and to view the cultural (versus racial) differences as "fun" (p. 90). Khanna and Killian (2015) found ICA parents in their study to have similar humanitarian impulses to "give back" or rescue "abandoned" children, but also found that some of the White parents sought to "diversify" [End Page 313] their family through adoption because of a perceived absence of culture within their own upbringing (pp. 581-582).

Ishizawa, Kennedy, Kubo, and Stevens (2005) found that non-White parents who adopt from abroad almost exclusively adopt from the same race or ethnicity as themselves, and more specifically they found that Asian American parents only adopted Asian children. Therefore, perhaps the parents' citing their own Asian heritage as a primary factor in choosing to adopt an Asian child (rather than a non-Asian child) may seem "natural." The respondents overwhelmingly found their common heritage as Asian/Asian Americans to be salient to their families' shared and individual identities. Alternatively, Ishizawa et al., suggested that the tendency for Asian American parents to adopt in-race may be related to the notion of "racial confidence," or lack thereof. That is, Asian parents may be reluctant to consider, or even be foreclosed from, adopting a non-Asian child because of societally-based racial barriers.

RACIAL-ETHNIC SOCIALIZATION

Racial-ethnic socialization encompasses the practices or strategies that parents utilize to communicate to their children regarding in-group identity and membership, as well as navigating intergroup or out-of-group relationships (French et al., 2013; Hughes, Rodriguez, Smith, Johnson, Stevenson, & Spicer, 2006; Rivas-Drake, Hughes, & Way, 2009; Stevenson & Arrington, 2009; Tran & Lee, 2010). Hughes and colleagues (2006) reviewed studies of racial and ethnic socialization, noting that racial socialization has been examined as a strategy within Black families, while socialization has been utilized in a broader context inclusive of Blacks and other groups. Racial socialization generally refers to the strategies parents utilize to promote positive self-esteem while also preparing children to navigate race-based barriers. Ethnic socialization derived from studying the ways in which immigrant parents sought (or not) to preserve culture, language, and in-group identity given societal expectations to assimilate. Despite the use of different terminology, they arguably "cover the same conceptual territory" such as in-group and out-group characteristics, identity, social status, stereotypes, and discrimination (Hughes et al., 2006, p. 748). The researchers therefore chose to conceptualize racial-ethnic socialization jointly, and categorized messages under four strategies: cultural socialization which includes exposure to cultural practices, history, traditions, and instilling in-group pride; preparation for bias, wherein parents teach their children ways to protect themselves from discrimination, prejudice, and racism; promotion of mistrust which entails communicating distrust and the need for caution with out-group interactions without providing adaptive responses; and egalitarianism and silence about race, wherein parents encourage their children to place more value on individual characteristics than group-based attributes or alternatively avoiding discussing race.

An understanding of the socialization practices of parents of biracial Asian American children in non-adoptive homes may also be salient in providing context for interracial adoptive couples where one parent is Asian American. Rollins and Hunter (2013) explored comparatively the racial socialization strategies of mothers of Black biracial and non-Black (Asian, Latino, Native) children. They found that mothers whose children were biracial Black were more likely to utilizepromotive socialization messages (meant to strengthen the child's sense of self [End Page 314] and transmitting culture) while passive socialization messages were communicated to non-Black biracial children wherein the mothers "deemphasized the salience of race through silence" (p. 143).

Less prevalent are stand-alone studies of biracial Asian Americans. Kasuga-Jenks (2013) sought to understand how parents communicate matters of race and ethnicity in her study of 12 families. She identified four themes; cultural practice, effects of interpersonal relationships, experiences of discrimination, and negotiating identity. She found that how the parents experienced discrimination in their own childhood and lives shaped how they communicated to their children about race. Chang (2015) also interrogated the experiences of multiracial Asian American children, finding that although the Asian American parents acknowledged race-based discrimination, 85% either had either no race conversations with their own parents or the conversations they did have were negative and unhelpful. The parents of biracial Asian American children tended to assume that living in a diverse, racially-integrated ecosystem to include family was sufficient to insulate their children from racism.

In summary, researchers have sought to understand the racial-ethnic socialization strategies parents use and whether they mediate or buffer the impact of racism and other structural inequalities (Hughes, et al., 2006; Kasuga-Jenks, 2013; Rollins and Hunter, 2013). However, there is a dearth of literature that explores racial-ethnic socialization as it pertains to "in-group" relationships within Asian American ethnic groups that may be salient to Asian parents who adopt other-ethnic Asian children.

Strategies to Address Race, Ethnicity, and Culture in Intercountry Transracial Adoptive Families

Research on White families who adopt internationally from Asia has focused largely on how parents navigate race, ethnicity, and culture with their children. Interestingly, intercountry adoption (ICA) in these instances seem to be viewed by parents as more about culture than race, especially with the earliest adoptions. Parents struggle with finding strategies to preserve their children's birth heritage and often rely on third-party instruction or exposure provided by culture camps, language schools, or motherland tours (see for example Huh & Reid, 2000; McGinnis, Livingston Smith, Ryan, & Howard, 2009; Rojewski, 2005). Ethnicity and culture have served as both a proxy and a way to circumvent discussions about race.

More recent scholarship has sought to examine the salience of race and ethnicity (culture seems to be subsumed into ethnicity) as distinct constructs and the relationship to adoptees' identity (Johnston, Swim, Saltsman, Deater-Deckard, & Petrill, 2007; Mohanty, 2013; Scherman, & Harre, 2008; Shiao & Tuan, 2008) situated within a broader conversation about racial and ethnic identity and racial-ethnic socialization. Vonk (2001) developed a three-part definition of cultural competence for transracial-cultural adoptive (TRA) parents drawn from a review of the literature and feedback from parent and experts in the field. The intent was to glean socialization practices needed to develop "positive racial identities and survival skills for life in a racist society" (p. 246). The definition includes: racial awareness, which refers to the parents' ability to assist their children in developing a positive racial identity and navigate [End Page 315] racism; multicultural planning, which refers to exposing children to birth culture and developing pride in their heritage; and survival skills, refers to arming children with strategies to respond to racism and developing healthy self-image. While her work focused on White parents that adopted non-White children, the skills may also have saliency for Asian American adoptive parents. Song and Lee (2009) surveyed adult Korean adoptees (n=67) to learn about their cultural experiences and the relationship between those experiences and their ethnic identity. Implicit in their cultural experiences are the socialization strategies their White adoptive parents utilized during their childhood, as well as their own choices as adults. The researchers identified seven socialization categories or strategies; organized Korean events (cultural camps and adoptee conferences), interpersonal Korean associations (exposure and interactions with other Koreans adopted or not), diverse milieu (living in diverse neighborhoods or communities), birth roots (travel to Korea and search), racial awareness (cognizance of being a racial and ethnic minority and a transracial adoptee), support (from family and friends), and cultural encounter (eating Korean food and learn Korean songs). Song and Lee posit that the more superficial low-investment strategies of organized Korean events and cultural encounters, which adoptive parents tend to gravitate toward, may be too remote to ethnic identity formation to have a positive correlation.

McGinnis, et al., (2009) conducted a comparative study of 468 adults (White domestic adoptees 156, Korean intercountry adoptees 179) who were adopted into White families in the United States. They concluded that adoptive status was more salient to the White adoptees, while the transracial nature of adoption and the meaning making of racial and ethnic identity were more primary for the Korean adoptees. Findings included that the Korean adoptees felt less connected with their ethnic group than the white adoptees, despite feeling more strongly ethnic identified; were more likely to experience discrimination based on race than adoptive status; and that they reported their "lived" experiences were most instrumental to their racial/ethnic identity. McGinnis et al., recommended that parents go beyond cultural socialization to strategies that promote racial and cultural identification to include birth country travel and search, diverse environments and role models.

The bulk of the literature on in-race intercountry adoption focuses on families with children from Eastern bloc post-Communist countries, primarily Russia and Romania (see for example Goldberg, 2001; Groze & Ileana, 1996 and Linville & Lyness, 2007; Robinson, McGuiness, & Pallansch, 2015; Scherman & Harre, 2008). The majority of the children have experienced some length of pre-placement institutionalization, leading researchers to explore questions about adjustment and long term impacts of early deprivation rather than racial-ethnic identity (Linville & Lyness, 2007). However, Jacobson's (2008) study focused more specifically on the racial-ethnic identity socialization of adopted children from Russia and China through the lens of culture keeping, "a mechanism for facilitating a solid ethnic identity and sense of self-worth" which serves to mitigate some of the challenges children face living in ethnically and sometimes racially diverse White adoptive families (p.2). Jacobson found that for parents with children from China, the interracial nature of their families drew parents to culture keeping practices, while the monoracial composition of families with children ofRussian descent kept parents away from culture keeping. The former viewed culture keeping as a strategy to protect [End Page 316] their Chinese American children living in a racialized society and to support their racial and ethnic identity development.

Overall, the adoption research has pointed to the importance of "high investment" socialization strategies that support children's identity as a racial and ethnic minority, and notjust cultural socialization (Song & Lee, 2009). Strategies are described in varying terms, but tend to include a diverse ecology that includes cultural (camps, language, traditions), relational (role models, peers, community), and experiential (lived experiences} to develop a positive identity in addition to communication about navigating the adoptees' minority status.

Strategies to Address Race, Ethnicity, and Culture in Intercountry In-Race Adoptive Families

Dorow (2006) and Louie (2015) have both explored comparatively the adoption of Chinese children into American homes which included some families where at least one parent was of Chinese descent. Dorow identified four narrative frames that captured the ways in which parents express and communicate their children's relationship to Chinese culture; assimilation, celebrating plurality, balancing act, and immersion. She observed that the Chinese American parents did not worry about authentic representation or the "right way to do Chinese culture" (p. 230) and did not view Chinese cultural identity as synonymous with the experience of being Chinese American. Interestingly both Dorow and Louie noted that while the Chinese American parents critiqued White adoptive parents' performance of culture, they did not examine their own despite noted fluidity and variance based in part on generation, strength of racial and/or ethnic identification, and location. Louie referred to this as privilege of authenticity.

Additionally, Louie's study highlighted the importance of socializing children to the experiences of being a racial minority in the U.S. rather than misguided emphasis on Chinese traditions. She noted that some of the Chinese American parents shared an awareness of being an Asian American as a "racialized and politicized" category.

METHODOLOGY

This mixed design study included questionnaires and interviews. The research design was approved by the University of Nevada, Las Vegas' IRB board, and prospective respondents were provided with study information through an Informed Consent. Participants indicated consent by completing and returning the questionnaire. There was a mix of family demographics where one of the parents was Asian American. If the couple was interracial, the parent who identified as Asian American was asked to complete the survey and/or was interviewed. If both parents were Asian American, the couple decided who wanted to respond and in one instance, both parents participated in an interview. All of the respondents completed the questionnaire and were invited to participate in a semi-structured interview. Due to the challenges of identifying Asian adoptive parents, participants were recruited by email announcements through adoptive family networks, to include Families with Children from China (FCC) and the Korean American Adoptee Adoptive Family Network (KAAN) listservs, and through snowballing. The majority of the parents resided in coastal states to include [End Page 317] California, New York, and Hawaii. While using a non-random sample limited the opportunity for a representative sample, the study is intended to provide a catalyst for future research.

The study was developed in two phases. Phase I was comprised of surveys which were sent to prospective respondents via email and returned either through the United States Postal Services or email. The survey was divided into three parts; Part I-14 demographic questions, Part II-four family composition questions, Part III-13 questions regarding motivation to adopt, family support, and parenting decisions related to adoption. The questions from Part III were based in part on other studies that have looked at motivation in adoption (Bergquist et al., 2003; Khanna & Killian, 2015), possible barriers in adoption for Asian American families (Bai, 2012; Lee, 2007; Mohanty, Ahn, & Chokkanathan, 2017). Part IV-three open-ended questions further exploring motivations to adopt, parents' expectations of their children's adoptive experiences, and what difference, if any, having at least one parent who is Asian American will have for their children. Phase II entailed semi-structured interviews, either inperson or by phone. All the in-person interviews were conducted by the first author and the telephone interviews were conducted by both the author and a research assistant. The findings ofthe Phase I are reported in this paper.

FINDINGS

Demographic Characteristics

For the purposes of this paper it is important to define some terms. Since the focus is on the in-race adoption ofAsian children, the U.S. Census Bureau's definition of"Asian" as a racial category is incorporated to include those with heritage deriving from the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent (Hoeffel, Rastogi, Kim, & Shahid, 2012). This imprecise definition clearly does not capture the distinct differences, even in phenotype within the Asian racial category. There also exists varied cultural, ethnic, and linguistic differences within this grouping which necessitates further distinguishing between inter-versus intra-ethnic placements; for example Chinese American parents who adopt a child from Korea versus China. Some ofthe parents and children are referred to as "bi-ethnic," meaning that they have mixed heritage, for example Korean American and Vietnamese American. Lastly, some ofthe parents are biracial, generally of mixed Asian American and White background, but for the purposes of this study are included in the ethnic group from which their Asian heritage derives. It is important to note that the term "identifies as" refers to the respondents' choices.

Parents

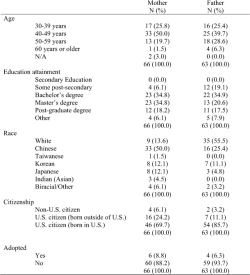

Sixty-nine families responded to the research request. One survey was eliminated because both parents were non-U.S. citizens and resided outside of the U.S., presumably they were in-country visiting when they completed the survey. Participation criteria specified that the person responding to the survey must be the parent ofAsian descent in instances of interracial couples. Sixty-eight completed surveys were included in the study. Nine ofthe respondents did not list a co-parent or spouse, two of the fathers were widows and the remaining seven respondents were either single or divorced. The total number of responses therefore varied from question-to-question [End Page 318] depending on whether the respondent included data of the divorced or widowed partner. The demographic characteristics ofmothers and fathers are shown in Table 1.

Demographic characteristics (N=68)

[End Page 319]

Half of mothers and over one-third (39.7%) of fathers are between 40-49 years old. Overall the parents are well-educated, professional, older, and most likely to be of Chinese American descent. Approximately one-third of both mothers (34.8%) and fathers (34.9%) received a bachelor's degree, which is the highest proportion of educational attainment among participants. However, the mothers overall had higher levels of educational achievement with 87.8% having completed at least a bachelor's degree, compared to 73% ofthe fathers. The majority of the parents are professionals, reflecting their high educational achievements. Approximately one-fifth ofthe mothers were full time stay-at-home moms (22.7%) however it is unclear whether they left the work force after the adoption.

The mothers in this study were more likely to be ofAsian American descent (80.2%) compared to less than half of the fathers (41.3%) who were mostly White. Notably, 62% of both mothers and fathers who identified as Asian American were Chinese American. Half of mothers identified as Chinese American, followed by White (13.6%), Japanese American (12.1%), Korean American (12.1%), and biracial or other (6.1%). Ofthe four mothers who identified as biracial or other; two were White and Chinese American, one was Chinese American and Japanese American, and one was Pacific Islander. The others identified as Indian American (n=3) and Taiwanese American (n=1). In terms of the fathers' race, over half of fathers identified as White (55.5%), followed by Chinese American (25.4%), Korean American (11.1%), Japanese American (4.8%), and biracial or other (3.2%). One ofthe fathers had mixed White and Hispanic heritage, and the other identified as Japanese American /Korean American. The fathers were more likely (85.7%) than the mothers (69.7%) to be born in the U.S, and more than two-thirds of both mothers (75.0%) and fathers (77.9%) have resided in the U.S. more than 20 years. The respondents' family configurations, which for the most part were interracial, reflected the high rate of out-of-race marriages of Asians in the United States, 28% in 2013 according to the Pew Research Center (Wang, 2015).

Few parents were adopted themselves; only 8.8% of mothers and 6.3% of fathers. All ofthe mothers who were adopted were of either Korean American (n=4) or Chinese American (n=2) descent, while all but one ofthe fathers who were adopted were White (n=3), the fourth was Korean-born. It is unknown whether the parents' adoptions were intercountry or domestic, but at least two ofthe mothers had been adopted from Korea.

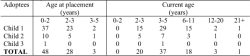

Children

The majority of participants (75%) did not have biological children, but already had an adopted child (73%), and 17.5% were considering working on adopting another. One family had three adopted children, and one-fifth ofthe families had two adoptees. Seven ofthe families were in the process of adopting and/or waiting for a child. There were a total of 79 adoptees. The youngest adoptee at placement was one month old, the oldest was five years old, and the average age was 11 months old. At the time ofthe survey the youngest adopted child was 12 months old and the oldest was 25 years old. [End Page 320]

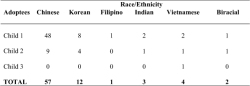

Over 80% ofthe adoptees were female and 72.1% were from China. The second largest group was from Korea (15.1%), followed by Vietnamese (5%), Indian (3.8%), and bi-ethnic (2.5%). All but one of the families who had adoptive children did so through intercountry adoption. The domestic adoption was through a public child welfare agency.

Adoptees' ages (n=79)

Adoptees' race/ethnicity (n=79)

Of the 61 families who had adoptive children in their homes, 75.4% (n=46) had at least one parent who shared the same ethnic and/or country of origin heritage with the child(ren). The majority were Chinese Americans (to include one Taiwanese American parent) who adopted from China (n=39) to include; one bi-ethnic parent (Chinese American and Japanese American heritage), one interethnic couple (Chinese American and Korean American), and one Chinese American parent who adopted from both China and Korea. Six Korean and two South Asian Indian families also adopted from their country ofheritage.

The 15 inter-ethnic placements were primarily Japanese American parents who adopted Chinese children (n=9) that included one couple with a parent who was Japanese American and the other parent who was Japanese American /Korean American. The other six families included; two Korean children who were adopted separately by Chinese American and Japanese American parents, a Chinese child with a Korean American parent, two children of [End Page 321] Southeast Asian heritage that were adopted separately by Korean American and Japanese American parents, and a Chinese American parent who adopted a Filipino child.

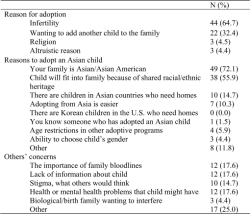

Reason for adoption

Descriptive Statistics

Participants were asked reasons for deciding to adopt by answering no more than two among six options: infertility; wanting to add another child to the family; religion; altruistic reasons; kin adoption; and other. The most common reason stated for adopting was infertility (64.7%), and half as many indicated that they wanted to add another child to their family. Very few parents reported being motivated to adopt based on altruistic or religious reasons, and there were no kin adoptions.

Participants were also asked reasons to decide to adopt an Asian child (see Table 4) and were given nine options developed from the literature (Bai, 2012; Bergquist et al., 2003; Khanna & Killian, 2015; Lee, 2007). The majority of parents answered "your family is Asian/Asian American" (72.1%) followed by "child will fit into family because of shared racial/ethnic heritage" (55.9%). Participants were asked how supportive their family and friends are about their decision to adopt using a 5-point Likert scale (1=Not at all supportive, 2=Somewhat [End Page 322] supportive, 3=Mixed, 4=Mostly supportive, 5=Very supportive). Overall the parents found their friends and family to be supportive with a mean of 4.17 for Korean American respondents, 4.42 for Chinese American respondents, and 4.44 for Japanese American respondents. As a follow-up question, they were asked about their concerns if they were not supportive, and given seven options. Twenty-four percent of participants chose "other" but largely expanded on the themes of preference for biological children and concerns about interethnic adoptions (i.e., Japanese American parents adopting a Chinese child).

Ethnic Group Analysis

Due to the non-random, small, and ethnically disproportionate sample, findings between the three Asian American ethnic groups (Korean American, Chinese American, and Japanese American) cannot be interpreted as significant. Rather, initial insights are limited to potential differences within Asian American adoptive parents. Additionally, since the majority of the respondents had non-Asian partners, the findings are further limited to their ecological context, and not monoracial Asian American adoptive families.

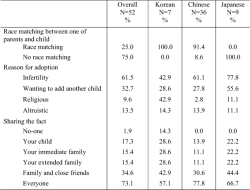

Descriptive Statistics and ethnic group comparisons (N=52)

[End Page 323]

Table 5 provides summary of questions by ethnic group. The total sample number of Korean American respondents was seven, Chinese American was 36, and Japanese American was nine. All ofthe Korean American parents, 91.4% of Chinese American parents, and none of the Japanese American parents reported mother's race match with their adopted child's origin of country. Approximately 43% of Korean American parents, 11.1% of Japanese American, and only 2.8% of Chinese American parents reported they adopted their children for religious reasons. The remaining reasons (infertility, wanting to add child, and altruism) did not vary meaningfully by ethnic group.

Figure 1 depicted the percentage of each answer among each group. Parents were asked, "With whom do/will you share the fact that your child(ren) is adopted?" and were instructed to select all that applied. Overall, the majority of participants (73.1%) shared with everyone. In terms ofethnic group comparisons, 14.3% ofKorean American respondents, while none ofChinese American or Japanese American parents reported they did not share their children's adoptive status with anyone. Almost 78% ofthe Chinese participants shared with everyone, compared to 57.1% ofKorean American parents and 66.7% ofJapanese American parents. It is difficult to know whether the parents have or intend to share with their child his/her adoptive status; for example only 13.9% ofthe Chinese American respondents indicated they would share information about adoption with their child(ren), while 77.8% indicated they would share with everyone.

Sharing the fact that child is adopted among Asian sub ethnic groups

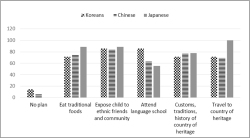

Figure 2 shows how parents teach their child about his or her cultural heritage among Asian ethnic groups. The major difference appeared on the attendance of a language school; 85.7% of Korean American participants reported their child attends or will attend language school, compared to 63.9% of Chinese American and 55.6% of Japanese American. However, Japanese American respondents reported that they were most likely to travel to the child's birth [End Page 324] country (100%) and eat traditional foods (88.9%). Approximately 14% ofKorean American parents and 5.6% of Chinese American parents reported they had no plan to teach their child about their cultural heritage.

DISCUSSION

Given the historical emphasis placed on race in adoption placement decisions and projected outcomes, this exploratory study of in-race adoption in Asian American families sought to provide some preliminary insight. There are several findings worth noting a) demographic profiles of adoptive parents, b) motivations for adopting, and c) the role of race/ethnicity in adoption.

Ways to teach children about cultural heritage among Asian sub ethnic groups

Demographic Profiles of Adoptive Parents

There are some similarities with this sample ofAsian American adoptive parents to non-Asian American parents that adopt Asian children in other studies. Both groups of adoptive parents tend to be older and well-educated with professional careers (Khanna, & Killian, 2015, Rojewski, (2005). The majority ofthe Asian American adoptive parents in this study were in their 40s (50% of mothers and 39.7% of fathers), similarly the average age of parents in previous intercountry adoption (ICA) studies range from 40 to 47 years (Bergquist et al., 2003; Khanna & Killian, 2015; Rojewski, 2005). The relatively older age of adoptive parents may result from time spent attempting to address infertility and wait times associated with adoption. Additionally, particularly for ICA, income requirements are intended to ensure that parents are financially sound, which often correlates to higher levels of education and professional careers. [End Page 325]

Other demographic findings reflect historical and sociopolitical realities in the U.S. with regard to race, population trends, and patterns of migration. In the case where one partner is non-Asian, White males were disproportionately overrepresented, which is congruent with White men and Asian American women being the most common mix of interracial marriage in the U.S. (Chen & Takeuchi, 2011). Most ofthe adoptive parents were of Chinese descent (50% of mothers and 25.4% of fathers) which may be correlated to the fact that the Chinese Americans are the largest and oldest Asian immigrant group in the U.S., and consequently have deep multigenerational family ties (Hoeffel, et al., 2012; Takaki, 1998). The inevitable increased acculturation and integration of Chinese Americans may contribute to an openness to consider formal adoption of a Chinese or other Asian child. However, population size alone cannot explain the varied prevalence of in-race adoption in Asian American communities. The next largest group of Asian Americans, Filipino Americans, was not represented in the study sample. This is likely due in part to the non-random sampling method, but may also reflect the limited availability of Filipino children available through ICA. This study found that the majority of interethnic adoptions were of Japanese American parents adopting Chinese or other Asian children. Although this finding was relevant for this study, it cannot be construed as reflecting a preference by Japanese American parents for non-Japanese children. Rather, it is congruent with the lack of availability of children for adoption from Japan, which would virtually foreclose an intra-ethnic placement of Japanese children. The frequency with which the children were Chinese may be largely because of availability since China currently adopts out the largest proportion ofchildren from Asia (USDS, 2018).

Given a choice, this sample of parents, seemed to prefer to adopt intra-ethnically. For the parents who were unlikely to be able to adopt intra-ethnically (Japanese American and Filipino American), Chinese children were chosen. Given the historical and sociopolitical histories between Asian countries, the role of country of origin as a possible mediating factor in adoption choices should be considered, but is beyond the scope ofthis study.

Motivations for Adopting

Parents seem to universally cite infertility as one of the primary reasons to adopt, which was also true for approximately 65% ofthe respondents in this study (Khanna, & Killian, 2015; Malm & Welti, 2010). Bergquist et al., (2003) found that White adoptive parents cited practical considerations such as wait times, circumventing age restrictions, and the ability to choose the child's gender as important in their decision-making. Additionally, adopting a foreign-born child for altruistic reasons or to diversify the family were factors for White adoptive parents (Bergquist et al., 2003; Khanna & Killian, 2015; Zhang & Lee, 2011). In comparison, the Asian American parents in this study cited racial and/or ethnic similarity and "fit" as the primary reasons they chose to adopt an Asian child.

The parents in this study reflected Ishizawa et al.,'s (2005) observations that shared heritage was integral for Asian American parents to adopt Asian children. They seemed to seek to minimize differences between themselves and their adopted children by largely choosing their own country of origin when possible, and Asia secondary because of the child's perceived [End Page 326] ability to fit into the family and a "shared racial/ethnic heritage." It was anticipated that the parents might report concerns about bloodline and stigma given preferences in Asian cultures for biological familial ties, however the respondents reported little concern (12% respectively). There are many factors that could mitigate such concerns to include the degree to which the parents are acculturated to the more non-traditional notions of family formation in the U.S. (interracial coupling, step or adoptive parenting, etc.), and selection bias such that parents who have decided to go through the very invasive process of intercountry adoption may have less hesitancy of external expectations or valuations. In contrast to historical closed or secretive adoption practices in Asia (Bai, 2012; Lee, 2007), the respondents overwhelming indicated that they were, or intended to be, open about their adoption.

Role of Race/Ethnicity in Adoption

The parents overwhelmingly cited shared racial and/or ethnic heritage as a motivating factor in adoption an Asian child. It is difficult to speculate as why they did not, or even if they did, choose to adopt interracially, and whether racial confidence was a factor (Ishizawa et al., 2005). Anecdotally, the lead author learned from conversations with Asian American parents who have foster-adopted domestically that they received referrals for Asian American children exclusively even though they indicated that they were open to any child, regardless of race or ethnicity. One ofthe common laments in the literature and in practice is that there is a scarcity of parents who are willing to adopt from communities of color (Bausch, Serpe, 1999; Hollingsworth, 1998; McRoy, Oglesby, & Grape, 1997). This certainly appears to be true for domestic adoptions in Asian American communities, and for this study which only included one family who adopted from a public child welfare agency. However, there is an absence of literature that examines the recruitment or prevalence of Asian American foster and/or adopt families. The parents in this study seemed to be unaware ofthe availability ofAsian American children in the U.S. in need of adoptive homes.

The parents' reports of how they plan to teach their children about his or her cultural heritage showed a desire to provide varied avenues from passive/low investment strategies such as eating traditional foods to active/high investment strategies such as enrolling them in language school or traveling to their country of birth (McGinnis et al., 2016; Song & Lee, 2009, Vonk, 2001). The data was examined to identify varying strategies between Chinese American, Korean American, and Japanese American adoptive parents, however cannot be construed as conclusive or representative. The Korean American parents overwhelmingly (85.7%) indicated they would enroll their children in language school, but were less likely to eat traditional foods and expose their children to customs and traditions. It is difficult to speculate, but perhaps the Korean American parents assumed that language school attendance will meet some of the other cultural and association needs for their children. Additionally, Korean American parents frequently enroll their children in language heritage schools in the U.S., often housed in churches, because the Korea government provides funding to encourage language preservation (Kim, 2011).

The Japanese American parents seemed to indicate a higher, although not significant, commitment to traveling to their child's birth country, exposing him or her to their ethnic [End Page 327] community, and eating traditional foods. However, all of the Japanese American parents adopted inter-ethnically, which may require a higher degree of commitment to connect their child to their birth heritage than for parents who adopted intra-ethnically. Additionally, the data does not provide information about whether or how the families that adopted outside of their ethnic group would nurture a bi-ethnic, or multi-ethnic, identity in their child. That is, it is unknown how a Korean American family that adopts from China might approach balance exposing their child to his or her Chinese birth heritage while raising them in an American/Korean American cultural context.

Perhaps more salient, especially for inter-ethnic adoptions, is racial-ethnic socialization and the development of an identity as an Asian in America. When asked which racial/ethnic group their child identifies with, the majority ofthe parents who had children in their homes (58.7%) indicated that their children either currently or are projected to identify as hyphenated Americans; i.e., Korean American, Asian American. An additional 39.6% of the parents indicated that their children would identify as non-hyphenated; i.e., Chinese or Asian. The parents overwhelmingly (94.1%) felt that having at least one parent who is Asian American would be "easier" for their children. They were asked to provide further explanation about their responses; generally they referenced themes of acceptance, fit, and identity congruent most strongly with the cultural competence skill of racial awareness (Vonk, 2001), the strategy of cultural socialization (Hughes et al., 2006), and interpersonal Korean associations (Song & Lee, 2009). It was not clear that the parents incorporated racial awareness (Song & Lee, 2009), survival skills (Vonk, 2001), and preparation for bias or promotion of mistrust (Hughes et al., 2006) to prepare their children to navigate race-based barriers and structural inequalities. It did seem apparent that the parents' responses were congruent with findings from Ishizawa et al., (2005), Dorow (2006), and Louie (2015) that simply being raised in Asian American families was more "natural" and that racial and/or ethnic socialization strategies did not need to be as deliberate. However, deeper discussion about the parents' practices and strategies with regard to racial-ethnic socialization is beyond the scope of this paper and will be reportedly separately with Phase II findings.

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of Asian American parents who adopt Asian children is largely unknown because of their seeming invisibility in the literature. This study resulted from the lead author's own experiences as a Korean adoptee and Korean American adoptive parent, and anecdotal awareness of other Asian parents that have adopted. The 68 families that responded to this study request cannot be construed as representative of Asian adoptive parents generally, however they provided a glimpse into their motivations for adopting and the ways in which race, ethnicity and culture have shaped their adoption decisions and strategies to nurture their children's ethnic and racial identity development.

The limitations in this study include a small, non-random sampling which precludes any meaningful statistical analyses. Snowballing heightened the risk of selection bias not only by including parents that are open and willing to talk about adoption, but also within the ICA community. However, the findings do provide direction for further research. Clearly, a national [End Page 328] representative sample would generate reliable data and capture the overall experiences of Asian American adoptive parents.

As with non-Asian American parents, the availability of children seemed to drive the choice of country of origin, and perhaps whether to choose ICA versus domestic adoption. However, further research could explore the sociopolitical historical context and implications of Asian American parents adopting inter-ethnically and concomitantly how they navigate multiple identities for their children. Presumably, the matter of culture and identity is more nuanced within and between Asian American ethnic communities. While this study focused on parents who adopted Asian children and unintentionally included almost exclusively foreign adoption, it is important to better understand the experiences of families who adopt (or foster-adopt) domestically—both Asian and non-Asian children.

This study did not shed any light on whether having at least one Asian American parent leads to better outcomes for adoptees, however this sample of adoptive parents believe that racial and/or ethnic identity are salient. Additionally, since a significant portion of the adoptive couples included a non-Asian American parent, the adoption is in part transracial despite the presence of an Asian American parent. Future research studies that have a larger sample population might be able to consider the experiences of same race and interracial parents in raising Asian adopted children. The long term important research is to measure the perspectives of adoptees raised by Asian American parents and situating their experiences within the research on ethnic-racial socialization. [End Page 329]