Project-Based Learning through the Eyes of Teachers and Students in Adult ESL Classrooms

The use of projects and project-based learning has recently received much attention as a way of promoting meaning-focused communication and integrating different language skills into second and foreign language classrooms. However, perspectives on the effective implementation of projects have not been fully explored. This study examines and compares ESL teachers’ and learners’ beliefs and attitudes toward project-based learning, as well as the extent and manner of project implementation in L2 classrooms. Data were collected from 118 participants (88 students and 30 teachers) through parallel written questionnaires in closed and open-ended sections, and through individual interviews. In addition to expressing positive attitudes toward projects in language classrooms, both teachers and students highlighted several advantages this approach has over traditional approaches to language teaching. However, they also expressed differing opinions on how projects should be implemented and what aspects of project-based learning should be emphasized. The implications of the findings for the effective use of projects in L2 teaching are discussed.

Le recours aux méthodes de l’apprentissage par projets a fait l’objet de beaucoup d’attention récemment, en tant que moyen de promouvoir la communication axée sur le sens et d’intégrer diverses compétences linguistiques aux cours de langue seconde ou de langue étrangère. Mais l’efficacité de la mise en œuvre des projets, elle, n’a pas encore reçu toute l’attention qu’elle mérite. L’étude présentée ici définit et compare les croyances et les attitudes d’enseignants et d’apprenants d’anglais langue seconde (ALS) concernant l’apprentissage par projets, en même temps qu’elle examine l’ampleur et la méthode de mise en œuvre des projets en classe de langue seconde. Les données ontété obtenues auprès de 118 participants (88 élèves et 30 enseignants), au moyen de questionnaires écrits parallèles à questions ouvertes et fermées et d’entrevues individuelles. En plus d’exprimer des attitudes favorables à l’égard de l’approche par projets en cours de langue, tant les enseignants que les élèves ont souligné plusieurs de ses avantages sur d’autres approches plus classiques. Leurs opinions différaient cependant quant à la façon dont les projets doivent être mis en œuvre et aux aspects de [End Page 13] l’apprentissage par projets qui doivent être privilégiés. Les conséquences des résultats pour l’usage efficace des projets en classe de L2 sont ensuite présentées.

project-based learning, teachers’ and students’ perspectives, adult ESL classrooms

apprentissage par projets, perspectives des enseignants et des étudiants, classes d’ALS pour adultes

Introduction

The use of projects and project-based learning has recently received much attention as a way of promoting meaning-focused communication and integrating different language skills in second and foreign language classrooms. However, how projects should be used effectively and what students and teachers think about their implementations has not been fully explored. The roots of project-based learning lie in the early twentieth-century progressive education reform movement that advocated a pedagogy emphasizing flexible critical thinking and looked to schools as an important place for generation of social and political change. During this era, John Dewey promoted action-based learning and experience as the forefront of effective learning. Dewey was a large part of a reform movement in the United States, mirroring many educational reforms previously proposed in Europe that also recommended experience-based, action-based, and perception-based education. However, although Dewey advocated experience as the basis of learning, the use of the terms ‘project’ and ‘project-based learning’ were not popularized until the 1920s, particularly with the writing of William Kilpatrick, who supported the notion of child-centred learning in education and educational projects (Kilpatrick, 1918; as cited in Legutke & Thomas, 1991, p. 157). Kilpatrick built upon Dewey’s ideas with The Project Method in 1918 and considered use of hands-on projects as an integral part of learning, emphasizing that effective learning is a process tightly connected to meaningful experience and a cooperative environment. A few other noteworthy European influences, such as Jan Comenius, Johann Pestalozzi, Maria Montessori, and Jean Piaget (Van Lier, 2006, p. xi), are considered to have contributed, in one way or another, to the idea of project-based learning. Piaget is frequently cited in the literature for his ground-breaking theory of cognitive development. He stated that “education, for most people, means trying to lead the child to resemble the typical adult of his society ... but for me and no one else, education means making creators . . . You have to make inventors, innovators—not conformists” (Piaget; as cited in Bringuier, 1980, p.132). Piaget would have supported the necessity for creativity in project-based learning. [End Page 14]

In more recent years, an influential work in the area of project-based learning has been Kolb’s (1984) seminal book, Experiential Learning. Following Dewey, Kolb viewed project-based learning as a form of experiential learning and believed that the theory of experiential learning provides something more substantial and enduring than traditional approaches to learning by offering “the foundation for an approach to education and learning as a lifelong process that is soundly based in intellectual traditions of social psychology, philosophy, and cognitive psychology” (p. 3–4). He viewed learning as a process where concrete experience was the basis for observation and reflection.

Defining project-based learning

In the field of education, the scope of the project-based learning approach is vast, and different names and perspectives have been used to define and describe it (see Stoller, 2007; Brydon Miller, 2006). These include, for example, experiential learning (e.g., Eyring, 2001; Legutke & Thomas, 1991; Markham, 2011; Padgett, 1994), investigative research (e.g., Kenny, 1993), problem-based learning (e.g., Savoie & Hughes, 1994), project approach (e.g., Levis & Levis, 2003; Papandreou, 1994), project work (e.g., Fried-Booth, 1986, 2002; Haines, 1989; Henry, 1994), and action-based learning (Finkbeiner, 2000).

In the field of language teaching, project-based learning has also been connected with content-based learning (CBL), as content is required as its theme or subject matter in order to begin the project (Alan & Stoller, 2005; Stoller, 2001, 2007). Although CBL uses projects, it often uses a series of informational sessions about a subject as its content, whereas project-based learning uses experience-related projects connected to the content through collaborative learning (Larmer & Mergendoller, 2010).

In general, task-based learning and project-based learning have many similar characteristics and areas of overlap. However, projects can be distinguished from classroom tasks in several ways. Tasks can be much shorter and are often carried out in one class. According to Willis (1996), tasks are “activities where the target language is used by the learner for a communicative purpose (goal) in order to achieve an outcome” (p. 23). A task has also been defined as an activity that has “a sense of completeness, being able to stand alone as a communicative act in its own right” (Nunan, 1989, p. 10).

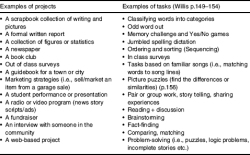

Projects, however, are more extended and “usually integrate language skills work through a number of activities” (Hedge, 1993, p. 276). Beckett (2002, p. 54) defined a project as “a long term (several weeks) activity that involves a variety of individual or cooperative tasks.” Projects involve not only gathering of information, but also [End Page 15] discussion of the information, problem solving, oral or written reporting, and display” and can be completed “outside the classroom in the students’ own time” (Hedge, 1993, p. 276). Project-based learning is largely group-based and relies on student input for its direction (Legutke & Thomas, 1991). According to Haines (1989), projects are activities in which “the students themselves play [a role] in the initial choice of subject matter and in the decisions related to appropriate working methods, the project timetable and the eventual ‘end product (p. 1).’” Thomas (2000) also stressed this aspect and added that, in project work, the focus is on collaboration and on how the goal is achieved rather than on the goal itself. He pointed out that projects are “complex tasks, based on challenging questions or problems, that involve students in design, problem-solving, decision making, or investigative activities; give students the opportunity to work relatively autonomously over an extended period of time; and culminate in realistic products or presentations” (Thomas, 2000, p. 1). The idea that projects are collaborative and ultimately achieve some kind of end result or reach some kind of goal is central to the definition of project-based learning. Both projects and tasks can take many different forms so it is sometimes hard to distinguish between them. The following table shows some examples of classroom tasks and longer-term projects that may help illustrate some of the differences.

A comparison of types of projects and tasks

[End Page 16]

From an examination of the types of activities teachers and students perform for tasks and what they do for projects, it is clear that projects require effort beyond one class and also often beyond the classroom. Project-based learning could be thus considered, in effect, a series of connected tasks focusing on content and the process of completing the tasks.

Research on project-based learning

As Beckett (2006) has pointed out, much has been written about project-based learning and many advantages of its use in language learning have been enumerated, including not only providing learners with ample opportunities to learn the language through engaging them in real-life activities, but also enabling them to develop new knowledge and various social and communication skills. However, only a few studies have explored empirically the use of project work in second language (L2) classrooms. One widely cited study is the Airport Project (Humberg et al. 1983), which was undertaken in Germany with a group of elementary learners (age 11) of English who set out to explore, as a project, the communicative use of English at the Frankfurt International Airport. The students spent three weeks before the trip to the airport preparing to interview English-speaking passengers and airline employees about their destinations, jobs, and opinions about Germany. The interviews were recorded and edited for use in future classes as sources of input. The findings showed that these elementary learners worked together well and were able to meet the challenge of the project task successfully. According to Legutke (1993),

They interacted successfully with a variety of English speakers from different parts of the world, generated, organized and processed input that was much more complex and interesting than what was offered by the school curriculum, and they prepared and provided input for fellow learners during follow-up lessons (e.g. their edited best interviews).

(p. 314)

They showed a positive attitude toward projects.

In one systematic research study, Beckett’s (1999) doctoral dissertation explores the implementation of project-based instruction in a Canadian secondary school class. Her study examined ESL teacher goals for, and ESL teacher and student evaluations of project-based instruction. Analysis of the observation and interview data for two teachers indicated that the teachers favoured project-based instruction because it allowed them to take a multi-skill approach to language teaching. Positive feedback was given with regards to project work as [End Page 17] providing contexts for their students to learn English functionally and enabling their students to discover their strengths and weaknesses. Beckett observed 73 students from Taiwan, Hong Kong, and China who were interviewed upon completion of their project work. According to observations and analysis of students’ written work, they acquired a significant amount of knowledge and skills through the use of projects. However, analysis of observations, interviews, and students’ written work found mixed evaluations. Only 18% of the 73 students said they liked project-based instruction, whereas 25% said they had mixed feelings, and 57% said they did not like it.

Although Beckett (1999) found positive opinions regarding project-based learning among teachers, Eyring (1989) found teacher evaluations to be mixed in a case study documenting only one US teacher’s experience implementing project-based instruction at the college level for the first time. The teacher was impressed by the students’ oral presentation skills, their design of a real-life activity as part of the project, and their writing a thank-you letter to some guest speakers. She also reported some frustration and tensions, however, as negotiating the curriculum with the students was often complex and demanding. She found that students complained that they were not learning the academic skills they needed while conducting projects. In the end, she reverted to more traditional, teacher-directed activities (Eyring, 1989, p. 113). This study also examined 11 Asian, European, and Latin-American students’ attitudinal and proficiency responses to this form of instruction. Although students made their own plans and seemed to have completed all the tasks as required, they felt a great deal of tension. They commented that allowing students so much input and giving them authority over their own learning was not good in an academic class. Many of the students reported a desire for a more traditional way of learning (teacher-centred instruction and studying vocabulary and grammar points separately).

Finally, Fang and Warschauer (2004) explored the use of project-based learning in the form of technology incorporated into traditional lecture courses in a Chinese university. Two project-based courses were examined using participant observations, surveys, interviews, and text analysis. The results showed that project-based instruction affected instructional methods and materials as well as learning processes and outcomes. There was an increase in authentic interaction when students used projects, as well as clearer relevance of the course’s content to students’ lives and careers. Teachers, however, found that using a project-based approach required far more time and effort than expected. Student-centred learning also clashed with the more traditional teaching methods of Chinese universities. [End Page 18]

Although a few studies have examined project-based learning and its use in instructional settings, as Beckett (2006) has noted, most of these have been conducted in subject-matter classes, while research on project-based learning in the field of second and foreign language learning is scarce. Furthermore, very few studies have directly compared both teachers’ and students’ beliefs and attitudes toward project-based learning. Therefore, we know little about how students’ and teachers’ opinions about projects compare and in what aspects or areas of project-based learning their perspectives align (Beckett & Slater, 2005). Since the success of project-based learning depends on both students’ and teachers’ opinions and on how they match, the present study set out to explore this issue by exploring how ESL teachers and students understand project-based learning and what they think about its use in language classrooms. The research questions addressed were as follows:

1. What are ESL students’ conceptions, beliefs, and attitudes about project-based learning and its different features?

2. What do they think are the frequencies of use of different PBL strategies in their own classrooms?

3. Are there any differences between teachers’ and students’ beliefs and attitudes toward project-based learning and the various strategies associated with its use in their classrooms?

Methodology

Participants

The study took place in three ESL schools in Victoria, BC, Canada. The schools offered intensive English programs for adult second language learners. An initial observation of several classes in these schools showed that their curricula were mainly communicative, with a focus on developing learners’ speaking and listening skills (the schools did not use the Canadian Language Benchmarks). The teachers were using a combination of instructional strategies, including a variety of inside – and outside-classroom projects. In total, data were collected from 118 participants – 88 students and 30 teachers. The student body consisted of both international students and immigrants living in Canada. Of the 88 students, 33 were males and 55 were females; 47 students belonged in the 18–25 age group, 17 in the 26–35 age group, 0 in the 36–45 and 56+ age groups, and 1 in the 46–55 age group. The nationalities included Korean, Japanese, Chinese, Taiwanese, Mexican, Syrian, Portuguese, Thai, Colombian, Indonesian, and Italian. They had been in Canada from two months to 10 years. All students were in upper intermediate or advanced levels, and all were from the [End Page 19] classes of participating teachers. The teacher group consisted of 13 males and 17 females with ages as follows: none in the 18–25 range, 4 in the 26–35 age group, 13 in the 36–45 age group, 5 in the 46–55 age group, 6 in the 56+ range and 2 unknown. The majority of the teachers had a BA plus some other English-teaching certification (i.e., TESOL, CELTA, RSA, Cambridge, or TESL). Their teaching experience ranged from 3 years to about 30 years. Data were collected over a three-month period.

Data collection

We used two data-collection means: a written questionnaire (teacher and student versions) and one-on-one interviews with a sample of teachers and students. The notion of project-based learning is broad and there are many different features that can be coupled with projects, so to get a deeper understanding of the participants’ thoughts, in addition to asking them what they conceived project-based learning to be and what they considered important about its use in general, we explored their opinions on the defining features of or strategies usually associated with project-based learning. We did so both through close-ended questionnaire items and through eliciting participant opinions when we were presenting them with examples of projects. We designed our questionnaire with four sections. The first was an opinion section, consisting of 10 Likert-scale statements. This section asked participants to express their opinions about the important components and strategies generally linked with project-based learning in the literature (e.g., Hedge, 1993; Legutke & Thomas, 1991; Thomas, 2000). The second section asked participants to report the frequency with which they had project-type experience in their classroom activities and employed teaching strategies generally associated with project-based learning. The project-example section presented participants with examples of projects usually used in language classrooms and asked them what they thought about them and how favourably they viewed their possible use in their classrooms. The open-ended questions asked participants what they thought about project-based learning in general and how they thought it should be implemented in L2 classrooms. In this section, they were also asked to express any other ideas they had or further explain any ideas they had expressed previously in the questionnaire items.

To develop the questionnaire items, we first designed a questionnaire for teachers (see sections I and II of the teachers’ questionnaire in Appendix A). A parallel questionnaire was then constructed for students by keeping the content of the questionnaire the same but modifying the instructions and changing some of the wording of the items so [End Page 20] that they were suitable for students as addressees (see sections I and II of the students’ questionnaire in Appendix B). The two questionnaires were then piloted with a group of teachers and students to check the clarity of the questions and the length of time needed to complete them. The students’ questionnaire was piloted with 23 students at the intermediate and upper intermediate levels in two different classes, and the teacher questionnaire was piloted with 9 teachers. The purpose of the pilot study was to determine whether any of the questionnaire items were unclear or problematic and also whether the participants had any feedback on the format and content of the questionnaire. In addition, the pilot estimated the amount of time the questionnaire would take teachers and students to complete. To this end, when taking the questionnaires, the participants were explicitly asked to identify any problematic or confusing items and also offer suggestions for clarity and improvement. They were also asked to keep track of the time and write it on the first page of the questionnaire. The average time was between 20 and 30 minutes for both students and teachers. After the pilot study, revisions were made to the problematic items, with a few of the questions being reworded and some new items being added.

In addition to the questionnaires, we carried out one-on-one interviews with a sample of 12 teachers and 15 students, all of whom were volunteers. The interview was semi-structured, with a set of specific questions. The goal of the interviews was to further explore teachers’ and students’ opinions about project-based learning and to provide them with opportunities to offer opinions beyond what was gathered in the questionnaire. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis. The students’ and teachers’ interview questions were designed to be as parallel as possible, with some questions being the same. The interviews took between 10 and 30 minutes for students and between 15 and 30 minutes for teachers.

Analyses

We first carried out quantitative analyses of the data from the first two closed-ended Likert-scale sections of the questionnaire. The data from the open-ended questionnaire items and the interviews were analyzed qualitatively. For the quantitative analysis, the means of the responses for both teachers and students were calculated. Non-parametric Mann– Whitney U tests were used to compare teachers’ and student’s responses because the data were derived from Likert scales, which do not represent an interval or ratio scale of measurement. Non-parametric tests also do not make assumptions about the shape of the distribution. The alpha level was set at p = .05 and all tests were two-tailed. [End Page 21]

Results

Quantitative analyses

Overall student and teacher perspectives on project-based learning

The first research question examined teachers’ and students’ perspectives on projects and project-based learning in general. To answer this question, we examined the first 10 questionnaire items, which explored teachers’ and students’ opinions about the important characteristics of project-based learning using a 6-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree (see Appendix A). Before the analyses, the overall reliability of these questionnaire items was calculated and the reliability estimates (Cronbach alpha) for the students’ and the teachers’ questionnaire items were 0.75 and 0.83 respectively, which we considered satisfactory.

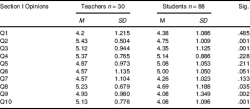

As Table 2 below indicates, the means of teachers’ and students’ responses for Questions 1, 4, 5, 6, and 7 were positive and also similar (with no statistical difference between the groups). Means ranged from 4.2 to 5.37 (i.e., partly agree to strongly agree). The features these questionnaire items explored included getting students to choose the topics for their projects (Question 1), going beyond textbooks (Question 4), getting students to experience real-life activities that involve going outside the classroom (Question 5), focusing on themes rather than individual linguistic items or skills (Question 6), and producing a final report for projects (e.g., a scrapbook collection of writing and pictures, a classroom display, a newspaper, a student performance, a radio or video program) (Question 7).

Although students and teachers had similar opinions with respect to the above characteristics, they differed slightly in their degree of agreement in some other aspects of project-based learning (Questions 2, 3, 8, 9, and 10). For example, one of the components of project-based learning suggested by Legutke and Thomas (1991) is the use of activities that encourage reflection (Question 2). Both teachers and students favoured such activities, but teachers were more positive (M = 5.43) than students (M = 4.75). The difference was statistically significant (U = 3.59, p = .001). Another component of project-based learning examined in the questionnaire was group work activities (Question 3). Both students (M = 5.12) and teachers (M = 4.35) were positive about this characteristic. However, the teachers were significantly more in favour of group-work projects than students (U = 3.26, p = .001). Another aspect of project-based learning on which students and teachers differed concerned teachers’ taking on different roles in the class [End Page 22] (e.g., facilitator, sharing, and/or instructor) (Legutke & Thomas, 1991) (Question 8). Teachers had a higher mean (M = 5.23) than students (M = 4.69) and the difference was statistically significant (U = 2.11, p < .05). Students and teachers also varied on giving different roles to students (e.g., manager, actor, writer, secretary, teacher, and/or researcher) (Legutke & Thomas, 1991) (Question 9). Teachers had a mean of 4.93 and students had mean of 4.08 (U = 3.13, p < 01).

Results of teachers’ and student’s overall opinions of aspects of PBL

The last questionnaire item, where students and teachers also differed, is working on a project for more than a single class session (Question 10). As projects are typically meant to last longer than a single lesson (Haines, 1989), this was a particularly important question to determine whether teachers and students enjoyed the continuity of a project. Both groups were in favour overall of continuous projects. However, the teachers favoured long-term projects (M = 5.13) significantly more than students (M = 4.08) (U = 4.57, p < .001).

Use of project-based learning

The second section of the questionnaire examined whether teachers and students had similar perspectives on the use of project-based learning in the L2 classroom. We asked them first to what extent they thought projects were used in their classrooms. However, since projects may mean different things to different people, we also asked them about the frequency of occurrence of various strategies associated with project-based learning (like those in the previous section). This helped us to compare what they believed about project-based learning and also to discover whether they thought these aspects of project-based learning occurred in their classrooms. Altogether, 14 parallel questionnaire items on students’ and teachers’ questionnaires [End Page 23] were designed to address the implementation issue, using a 6-point scale from never to almost always. Topics ranged from the use of various inside and outside classroom projects to giving free project choices to students or asking them to choose topics for their own discussion. Students’ and teachers’ responses were analyzed separately and then compared to determine their congruence. Before the analyses, the overall reliability of these questionnaire items for the students’ and the teachers’ questionnaires was calculated and found to be acceptable (Cronbach alpha = 0.76 and 0.77 respectively).

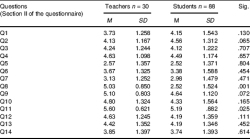

Overall teacher and student frequency of use of project-based learning

Overall, both teachers and students believed that strategies associated with project-based learning were used in their classrooms (Table 3). The ones believed by both students and teachers to be least often used were giving students opportunities to choose topics for projects and giving students the use of the Internet to research a particular topic. Students and teachers differed in their opinions about the use of small groups to practice listening and speaking (Question 11). On this item, both teachers and students indicated that such activities were often used in the classroom, but the teachers believed that these practices were used more often than did students (U = 3.24; p = .025). The other strategies were said to be used from often to almost always, with no significant differences between students’ and teachers’ opinions. Of course, in Table 3, the response to questionnaire item 8 shows a statistically significant result. This question was about a feature that can be associated with project-based learning – student-centredness. However, the results do not indicate that the teachers and students had different opinions because the wording was opposite. [End Page 24] Questionnaire item 8 for teachers was, “My classes are learner-centred”; for students it was, “The teacher is the one talking in the classroom.” Teachers had a mean of 5.03 and students had a mean of 2.52.

Qualitative analyses

Data from open-ended questionnaire items

Data from open-ended questions were analyzed qualitatively. To this end, an inductive approach was adopted in which the responses were read and re-read and main ideas and themes were derived from the participants’ statements. The derived themes were then compared with each other and also to the means of the teachers’ and students’ answers in close-ended questionnaire items to see to what extent they confirmed their responses.

The first question for the teachers asked their opinion about getting students to help plan a project. The responses were generally positive, although some also expressed reservations. One teacher said,

In theory, it’s great, but the reality of an intensive ESL program is that you often don’t have the time to allow student input to a great degree (i.e., determining curriculum). Even choosing partners can be problematic – after you have students who shouldn’t work together (bad influences) . . .

Another teacher responded,

In general, I agree with the students guiding themselves. However, this for me depends on the students, [and] class make-up; especially in terms of motivation.

Some important reasons provided by the teachers for not using projects were time restrictions as well as motivation and autonomous learning, with five teachers commenting on the latter.

The second question elicited teachers’ reactions to the idea of collaborative learning, which lies at the heart of project-based learning. The majority of the teachers expressed positive attitudes toward collaborative learning and were very quick to point out that it is the process, not just the end product, which is important in project-based learning (nine times in the data). One teacher wrote, “The language generated throughout the process is the objective; cooperation and sharing of ideas, [as well as] verbal interactions are crucial. The end product is assessed, but not the goal of learning.”

Teachers were also asked to provide examples if they had used projects. Eighteen teachers out of 30 reported that they had used some [End Page 25] kind of project in their classrooms. Five said they had done it “sometimes” or were not clear if their activities were actually projects. Among the examples they provided were group presentations, seminar discussions, a photo-novel project (like a comic book with captions and text), community volunteer work, symposiums, news programs, current events, collecting food for the food bank, and a newspaper project. These examples show that teachers may have different interpretations of what a project is, but they all believed that a project is a meaning-focused activity with some collaborative component.

The first question in the students’ open-ended questionnaire asked if the students liked to do projects as a classroom activity. An overwhelming 70 students were positive and used a variety of words or phrases to describe their attitudes including “interesting,” “motivating,” “helps you with English skills,” dynamic,” “increase the participation of the students,” “confident to speak,” “learn what teamwork is,” and “achievement.” Students were also asked if projects are a good thing to do. Responses were mixed, as some students felt group work was difficult, due to a lack of participation or effort from all the group members, a common complaint in any teamwork situation. For example, one student wrote, “Sometimes it is good, but sometimes it is not good. Because some of my group members don’t participate and they don’t make an effort. So the other members have to do that by themselves.”

Another question asked was whether they had worked on any projects before their current class and if so, what they were. The majority of the students indicated that they had some experience with projects, such as interviews, a book club, making a map, making a TV program, natural resources research, a video clip imitating Pirates of the Caribbean, a marketing project, and designing a future recreation centre. Students believed that these projects provided them, not only with real-world experiences, but also with opportunities for language learning. Each student perceived these activities as projects because they involved a series of tasks resulting in an end product achieved through collaborative means.

Teacher and student interviews

Altogether, a sample of 12 teachers and 15 students was interviewed using nearly identical questions. Specific questions were concerned with what they thought project-based learning is, examples, goals, strategies to implement project-based learning, effectiveness, length of time of a project, comparisons with traditional (teacher-centred) teaching, student autonomy in planning, and advantages and disadvantages. [End Page 26]

In terms of their perception of project-based learning, several teachers mentioned using real-world or theme-based tasks and activities, as well as emphasizing collaboration. They also mentioned that projects should be hands-on, be interesting, and involve information sharing. As for the goals of project-based learning, both teachers and students mentioned a wide variety of goals, such as producing and improving language, learning how to work collaboratively, learning how to collect information, using authentic language to share that information, negotiating with each other to accomplish a task, promoting interest, and helping students integrate into the community. However, differences emerged between the two group’s responses. Whereas, for teachers, project-based learning was seen as an experience-based strategy for both language and content learning, students tended to view projects as a kind of real-world task focused on learning content and learning how to do the task itself. For example, one student commented that learning “how to do this project before we go to university [. . . is] very helpful for us to do research paper or project in university courses.” Another area of difference was that, while for teachers, projects integrated all four language skills, for students, the aim of projects was seen more as a way of fostering speaking skills. In general, students felt that their teacher wanted them to practise speaking more often through the discussions surrounding the project.

The effectiveness of project-based learning was also explored in the interview. Eleven out of 12 teachers considered projects effective. Some of the reasons included ideas of collaboration, discovering new things, retention of language due to personal involvement, meaningful content, integration of skills in an authentic way, and motivation. Teachers were asked to make comparisons between a project-based approach and more “traditional” teaching. Their answers were wide-ranging (Table 4) and indicate that they had a clear understanding of what project-based learning is. As can be seen, their answers were in line with what has been mentioned in the literature about the characteristics of these two approaches.

Discussion and conclusion

According to the quantitative results in the opinion section of the questionnaire, teachers showed more positive attitudes than students toward project-based learning in general. Although, in some of the areas, these differences were not substantial, an overall stronger agreement of teachers was most apparent in the following areas: the use of reflective activities for students, getting students to work on projects in groups, using a variety of materials, producing a final product, [End Page 27] assuming different roles (for teachers and students), and working on a project for more than one class. Students had positive opinions about project-based learning in general, but they were less positive than teachers in several areas. For example, group work seemed to be a debatable topic for students, as they did not have as positive an opinion about this strategy as teachers did. This finding is particularly interesting, as projects are typically considered to last longer than a single lesson (Haines, 1989).

Teacher comments comparing traditional teaching with project-based learning

The interview data further affirmed the above findings and provided additional insights into the teachers’ and students’ perspectives toward several key areas related to project-based learning, including examples of projects they used, goals of projects, strategies to implement projects, effectiveness of projects, desirable length of time for a project, and some of the advantages and disadvantages of project-based teaching compared with traditional teaching.

Almost all the teachers in the interviews indicated that project work is an effective strategy for learning language. They also thought that projects can take many different forms and that all forms of projects could be effective if implemented appropriately in the classroom. However, they also regarded student presentations as a common project in the classroom. The more frequent use of presentations may have been due to the communicative qualities of presenting and to the listening and speaking practice involved. [End Page 28]

Other aspects of project-based learning that were emphasized by teachers were its learner-centeredness and its encouraging students’ involvement and participation in classroom activities. Students provided similar responses, but differed in other respects. For example, for teachers, allowing students opportunities to pick topics was of uncertain value. Teachers maintained that they were hesitant to do this consistently due to time factors and conflicting interests. Students were expected to be in class during class time and participation out of class would have to be through an organized trip with clear expectations. Students were occasionally sent, after class, to collect information for homework assignments but the approach was not emphasized. This is surprising in light of the fact that using the community and resources outside of class is frequently heralded as creating more motivation for learners (Eyring, 1989). One reason could be that sending students outside the classroom during class time might be inconsistent with the prescribed curriculum and the scheduled class times for these schools.

In general, teachers may have agreed more with many of the attributes of project-based learning than students because of their need for a dynamic and interesting classroom and for providing meaningful situations for learning (Mitchell et al., 2009). Teachers’ tendencies to be flexible could also have been due to the multi-cultural make-up of their classrooms – this may have affected their willingness to try different teaching methods. Teachers’ emphasis on the collaborative aspects of project-based learning may have also been due to their having been trained in current teaching approaches that involve collaboration – approaches that include task-based learning, the communicative approach, and content-based learning. Thus, teachers’ past education may have affected their beliefs about what strategies were effective in their classrooms.

Teachers must consider the cultural backgrounds of the students when implementing projects. For example, the less positive attitudes of the learners in this study toward group work activities can be explained in terms of learners’ educational and cultural differences. Students who are accustomed to traditional methods of teacher-centred language teaching may not be used to doing group-work projects and therefore may not feel comfortable with such activities. When students are the recipients of information and are “only in a position to notice teachers’ actions and their influence on them as students, they are not in a position to be reflective and analytical about what they see, nor do they necessarily have cause to do so” (Denise, Mewborn, & Tyminski, 2006, p. 30). Students who are taught this way are likely to express discontent about a teacher or practice that is different from [End Page 29] ones they have previously experienced. Doubtless, teachers should consider the students’ goals and objectives before using any classroom instructional strategy, including group-work projects. For example, for students whose goal is to learn basic day-to-day English, project-based learning connecting them to the surroundings they live in can be beneficial. For other learners, who may be more academically oriented, project work that enhances academic skills, including critical reading, writing, and thinking may work best.

To overcome some of the differences between the teacher and the students, it is important for the teacher to make the goal, the skills developed, and the resources available for doing the project explicit (Beckett & Slater, 2005; Dooly & Masats, 2011). Dooly and Masats (2011) have proposed training and modelling of the approach and its features for both students and the teacher in teacher-training programs. Regardless of the teaching approach, or method or technique used, if students and teachers are quite clear about the goals and expectations of any new method, its potential for effectives and success increases.

Although the present study yielded several important findings, a number of issues need to be considered when interpreting the results. First, for the purpose of this research, projects were considered as experiential tasks that involve learners in real-life experience. However, from the data, it appears that teachers in adult ESL classes interpreted projects in many different ways. Teachers sometimes understood project-based learning as anything learners do both within and outside the classroom. This is an interesting finding, but further research is needed to separate what distinguishes project-based learning from other approaches and determine how to measure whether teachers use it or not. Furthermore, due to the broad nature of a project (Stoller, 2001), a single definition may not be possible. The questionnaire in this study was designed to encompass the most salient features of project-based learning as defined in the literature and to examine what features were used most often in these classrooms. However, it is also useful to determine why students and teachers vary in their interpretation of what a project is. Thus, further study is needed to explore why teachers and students have different definitions or conceptions of projects.

The way teachers and students interpret the usefulness of an instructional strategy depends heavily on their past experiences with that method. Therefore, another area that can be examined is students’ and teachers’ perspectives according to their culture and their educational background. Indeed, several comments in the present study as in Beckett’s (1999) referred to an Asian predilection for traditional [End Page 30] methods. Thus, it would be helpful to see if students from different cultures have the same opinions about the use of projects. Finally, the chief aim of this study was to examine participant understanding of project-based learning and discover what they thought about its different components. However, it would also be interesting to evaluate project-based learning as a method when it is first implemented in a series of L2 classrooms and then evaluated for its usefulness.

References

Appendix A. Project-Based Learning Questionnaire: Teacher Questionnaire

Section I

In the following section, please indicate your opinion after each statement by circling the number that best indicates the extent to which you agree or disagree with the statement.

For example, if you strongly agree with the statement, circle 6. If you strongly disagree with the statement, circle 1. Please circle one (and only one) whole number after each statement and answer all.

| Statements | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Slightly disagree | Party agree | Agree | Strongly agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | I like the students to determine topics for discussion when I assign group work. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 2. | I like to use activities that encourage reflection. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 3. | I like to use group work which is focused on a theme or is project-based. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 4. | I like to use a variety of materials in addition to textbooks (e.g., films, Internet, and people from the Victoria area). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 5. | I like students to experience hands-on and real life tasks or activities which involve going outside the classroom. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 6. | I like it when my classes are focused on content and an ongoing theme rather than individual linguistics items or skills. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 7. | I like it when my class produces a final product (e.g., a scrapbook collection of writing and pictures, a formal written report, a classroom display, a newspaper, a student performance, a radio or video program). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 8. | I like it when I assume different roles in class (e. g., facilitator, sharing, and/ or instructor). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 9. | I like it when students have to assume different roles as well (e.g., manager, actor, writer, secretary, teacher, and/or researcher). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 10. | I like students to work on a project for more than a single class session. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

[End Page 34]

Section II

In the following section, please indicate the frequency with which you do the following activities. Please circle 6 if you almost always do this type of activity in your class and circle 1 if you never do this type of activity in your class.

| Statements | Never | Almost never | Sometimes | Often | Usually | Almost always | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | I give students many opportunities to choose topics for discussion. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1. | I have students reflect on their work through journals or discussions. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 2. | I let students work on one project for more than one class session. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 3. | I use a variety of materials in addition to textbooks(e.g., films, Internet, and people from the Victoria area). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 4. | I send my students outside the classroom during class time to collect information for class-related work. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 5. | I send my students outside the classroom after class to collect information for homework assignments. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 6. | I have students proofread each other’s written work. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 7. | My classes are learner-centred. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 8. | Completing activities or projects in class requires everyone to contribute and participate. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 9. | I grade my students mainly through an ongoing collection of their work and do not rely solely on tests. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 10. | I get students to practice listening and speaking in small groups. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 11. | I have short grammar lessons based on student needs. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 12. | I investigate topics in the community or real-world issues (e.g., elections, the environment, public transportation etc.). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 13. | I use the Internet to research a topic. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

[End Page 36]

Appendix B. Project-Based Learning Questionnaire: Student Questionnaire

Section I

In the following section, please indicate your opinion after each statement by circling the number that best indicates the extent to which you agree or disagree with the statement.

For example, if you strongly agree with the statement, circle 6. If you strongly disagree with the statement, circle 1. Please circle one (and only one) whole number after each statement and answer all.

| Statements | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Slightly disagree | Party agree | Agree | Strongly agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | I like giving the teacher ideas for topics to discuss in class. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 2. | I like talking about and thinking about things I did in class (e.g., journals, group discussions about projects we do in class.) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 3. | I like working on projects in groups. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 4. | I like to use a variety of materials in addition to textbooks (e.g., films, Internet, and people from the Victoria area). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 5. | I like going outside the classroom to do activities or get hands on experience. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 6. | I like it when my classes have a lot of real-world topics and relate to the community (e.g., elections, the environment, local issues, etc.) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 7. | I like working toward a final product in class (e.g., a scrapbook collection of writing and pictures, a formal written report, a classroom display, a newspaper, a student performance, a radio or video program). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 8. | I like it when my teacher has many different roles and I see him/her as more than just a teacher. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 9. | I like having different responsibilities and roles in class (e.g., group secretary – writing down information, Internet expert, presenter, or organizer, etc.) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 10. | I like working on one project for more than one class. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

[End Page 37]

Section II

In the following section, please indicate the frequency of how your teacher uses or does not use the various aspects of teaching. Please circle 6 if he/she almost always does this type of activity in your class and circle 1 if he/she never does this type of activity in your class.

| Statements | Never | Almost never | Sometimes | Often | Usually | Almost always | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | My teacher gives me many opportunities to choose topics for discussion. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 2. | My teacher gets me to talk or write about what I learn in class and what I think about it. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 3. | My teacher gets me to work on one project for more than one class session. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 4. | My teacher uses a variety of materials, e.g., in addition textbooks; she/he uses films, Internet, and people from the Victoria community. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 5. | My teacher sends me outside the classroom during class time to collect information for class-related work. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 6. | My teacher sends me outside the classroom after class to collect information for homework assignments. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 7. | I help read and correct my classmates’ written work. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 8. | The teacher is the one who talks in the classroom. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 9. | Completing activities or projects in class requires everyone to contribute and participate. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 10. | My teacher evaluates me mainly through an ongoing collection of my work and does not rely only on tests. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 11. | My teacher gets me to practice listening and speaking in small groups. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 12. | My teacher has short grammar lessons based on my needs. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 13. | My teacher gets me to investigate topics in the community or real-world issues (e.g., elections, the environment, public transportation, etc.). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 14. | My teacher gets me to use the Internet to research a topic. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

[End Page 39]