The Mindset:Tackling The Challenges of Old Age Care in Communities in China

In policy analyses, the mindset of policymakers is crucial to determine the governing culture, incentivise stakeholders and assess the policy outcomes. By examining the policies associated with community-based care, this article analyses how policymakers have responded to the needs of old age care in China. The research establishes that China has shifted from a fixed to a growth mindset, which anticipates a growing investment in community-based old age care services. However, after the initial excitement, the growth mindset, being fixated on the economic perspectives of the old age care service system, has become a constraint, especially if the performance indicators are not set to improve the quality of care and the development of human resources in age care. It is time to move one step further to adopt a "benefit mindset" that is centred around addressing the needs of older people.

INTRODUCTION

Chinese policymakers have long recognised the risks that a fast-ageing population may pose to the economy and to society.1 Policy advisers and policymakers have raised the concern of "growing old before becoming rich" (weifu xianlao) for quite some time in China. A 2002 article published by the Advisory Group on Issues and Response [End Page 148] Strategies for Population Ageing in China is the earliest known document in China that mentions this concern.2 The said article argues that people aged over 65 years old in China had reached 90.62 million in 2001, accounting for 7.1 per cent of the total population and thus marking the beginning of the era of population ageing. It is estimated that in the first half of the 21st century, population ageing would continue to increase as the economy grows. According to the 2020 population census, people above 60 years old would hit 18.7 per cent of China's total population in 2020, compared to 13.3 per cent in the 2010 census.3 The feature of ageing in China highlighted in the article's true-to-life phrase "growing old before becoming rich" instantly captured the imagination of the general public and attracted wide media coverage. The precise meaning of the phrase (at what age a person is considered "old" and how much one possesses to be considered "rich") has confounded the public. The mention of the phrase in Tian Xueyuan's article that appeared on 16 November 2004 in the People's Daily formally acknowledges that "growing old before becoming rich" is an important social issue. In 2005, the World Bank began to discuss how to address the issue with the Chinese government. Since 2005, the phrase has frequently emerged in public discourse and other developing countries, such as Sri Lanka, have also started to discuss these issues.4

Within China, there had been growing fear of population ageing.5 However, identifying the "needs" and "problems" and calling the "crises" have for a long time not translated into effective solutions.6 The Chinese government was reluctant to take responsibilities for old age care and relied heavily on the private market. Policy foci were on setting up a social insurance system assuming that as long as people are able to pay, the market would come up with the solutions and be able to deliver the services needed. The situation has changed since 2015 when the government started to commit greater efforts to develop an old age care service system by introducing national policy guidelines. Nevertheless, there are persisting challenges in the care system. [End Page 149]

This article examines China's policy transition in confronting the old age care crises that are looming large and explains the underlying barriers to improving the service system. Based on the fixed–growth–benefit mindset theory, the authors argue that the mindset of the policymakers can affect the outcomes of old age care services. This research develops a three-element mindset shift framework and analyses the changing mindsets over the years. The analyses are based on official statistics and secondary data. The analyses help to identify potential future issues, such as a serious mismatch between community-based old age care supply and elderly people's needs. The authors' findings in this article recognise the necessity to change from the growth mindset to benefit mindset.

THEORY OF MINDSETS

A mindset is a set of assumptions, methods or notions held by individuals or groups.7 Existing literature has identified several strands of mindset theories. These strands are: (i) a scarcity or an abundance mindset that may affect consumer decisions;8 (ii) a rating or non-rating mindset that may change the way marketing strategy is designed or how employees or even users are motivated;9 (iii) a planning or a no-planning mindset that could affect people's virtual attention in decision-making;10 (iv) a fixed, growth or benefit mindset that has effects on different attitudes towards the possibility and meaning of "success";11 (v) a global or a local mindset which may affect the willingness for international collaboration and innovation;12 (vi) the adoption of a cooperative or uncooperative mindset instrumental, respectively, to the success or failure of health-care reform in many countries.13 As indicated in some of these categories, Buchanan and Kern suggest that mindset theories can be expanded beyond psychology to other fields such as education, business and policy analyses.14 [End Page 150]

The mindset concept has been used to analyse the behaviour and decisions of private and public organisations,15 non-governmental organisations16 as well as the family as a social institution.17 There is a growing interest in how the mindset of top decision-makers/managers may affect their behaviour and the impact on the organisational culture.18 Some studies have applied mindset theories on policy analyses to investigate how policymakers or the society as a whole respond to a looming social issue or even crisis. This has been discussed extensively in the literature on various countries' determination to address climate change. For example, while people may generally recognise and are concerned with the problems associated with climate change, the majority do not take mitigation actions and they also do not believe that their actions will make a difference.19

The mindset of policymakers is an important part of policy analyses. In the policy context, the behaviour of policymakers may also be affected by the mindsets of decision-makers, who may be either individuals or the policy system.20 Unlike the psychology of an individual or an organisation, a government is a collective of multiple agencies that may have varied departmental interests, which can often be in conflict with each other. Therefore, it is difficult to pinpoint who is THE "policymaker" and HIS/HER mindset, even though China is an authoritarian system in which the national leaders may command a much greater power in influencing policy agendas.

The mindset theory is useful not only for analysing the state of mind of the policymakers in each policy field at a given time, but also for comparative analyses. For instance, it is argued that a non-cooperative mindset is a barrier to solving certain complex problems, hence a shift to a cooperative mindset would made a difference. [End Page 151] Therefore, a framework of different mindsets defined by a set of variables can be used as alternative mindsets for comparative analyses. In this sense, the mindset can potentially be an independent variable that drives changes or shows contrasts between different jurisdictions. Mindset can also be a dependent variable. For example, in a governing system, the mindset at the top level may affect the mindset at lower levels21 or a mindset change of a stakeholder may have ripple effects across networks or communities, or across different sectors or jurisdictions, resulting in policy diffusion.22

FIXED MINDSET, GROWTH MINDSET AND BENEFIT MINDSET

To understand the impact of mindset on community-based old age care, the authors explore the fixed, growth and benefit mindset theories. Dweck argues that the belief of one's own intelligence and abilities as immutable and thus not improvable through efforts can affect a person's ability to learn and grow.23 People with a fixed mindset tend to avoid facing up to challenges, reject criticism and give up easily when they encounter failure. People with a growth mindset are not afraid of failure and are willing to learn and improve.24 The fixed and growth mindset theories suggest that the mindset one adopts profoundly shapes one's ability to learn and to be successful.25 This mindset theory has been applied more broadly.26 The benefit mindset is a newer development in the theory that builds on the intention to serve the well-being of all and emphasises the need to take consequent actions. A person with a benefit mindset tends to be supportive of a growth mindset but will further query whether such growth would improve the well-being of society. Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the three mindsets.

The terms "fixed mindset", "growth mindset" and "benefit mindset" are used rather loosely although there have been numerous references to policymakers' or a leadership's mindsets. In the context of governance, fixed, growth or benefit mindset relates to the management style of an organisation. For example, leaders with a fixed mindset tend to monitor employees' target-setting and congratulate them based only on results, whereas leaders with a growth mindset focus on efforts and praise employees for them. Leaders should serve as mentors and give employees opportunities to develop [End Page 152] and train.27 Since leaders with a benefit mindset would tend to seek the actual benefit to humanity, they would call for the involvement of an increasing diversity of stakeholders. In this sense, growth should be associated not merely with the government agencies and officials involved, but also with the potential to enhance the well-being of the members of society.28 However, the organisational mindset is inadequate to understand how a government would respond to certain issues or crises. In particular, in the context of social policies, policy actions or inaction are often driven by the government or a policy network.29

Fixed–growth–benefit Mindsets and Their Behavioural Outcomes in Individuals

The authors apply the fixed, growth and benefit mindsets in this article to analyse the policies and outcomes of community-based old age care and the role of the government's mindset in bringing about policy changes.

METHODOLOGY

The authors utilise and analyse the official statistics of the Ministry of Civil Affairs and second-hand data that include both quantitative and qualitative data in existing publications.

The authors apply the fixed, growth and benefit mindsets framework proposed by Buchanan and Kern to examine the policy strategy in relation to China's challenges of old age care according to each mindset, and the strengths and weaknesses of the corresponding policy strategy.30 The fixed, growth and benefit mindsets theory is used to analyse the mindsets of decision-makers or leaders. In practice, it is not possible to observe the mindset of policymakers by treating them as an individual or an organisation because policies of such complexity are formulated by many people in various [End Page 153] departments in the government. It is therefore necessary to focus on the policymakers' actual responses, the policies and actions in addressing the challenge by examining the national policies. Basing their study on published policies, the authors attempt to analyse the mindset of policymakers by examining the policies as they are published. Using this method, it is possible to identify whether the policies are intended to address existing policy issues, the underlying ideology, the institutions, the role of the state or the principles used to decide whether actions will be taken. For the analyses, the authors review the policies on old age care services since 1978, and establish the priorities, the framing of the policy issues, and the solutions. The purpose is to establish the mindsets of the policymakers. Table 2 applies the fixed mindset, growth mindset and benefit mindset framework to analysing policies.

Mindsets of the Government and Public Policymakers

COMMUNITY-BASED OLD-AGE CARE IN CHINA

Persistence of Fixed Mindset (Prior to 1978)

From 1978 onwards, China decided to shift from the central planning economy to a market economy, and pursue economic growth. A series of changes was introduced, demonstrating the government's willingness to make a paradigm shift in order to address social issues. There was a general change in the mindset in all sectors that most researchers analysed as a shift from the central planning era to a transitional era in which marketisation and privatisation have played dominant roles. As a result, privatisation took place in many sectors, such as housing, schooling and health care.31 [End Page 154]

However, changes in the old age care sector are rather different. Prior to 1978, old age care was an amalgamation of Confucian values and the communist system, with the former playing a greater role. In such a system, old age care was the responsibility of the family or the extended families of the older people. Children should look after their elderly parents until they pass away. When an elderly person did not have anyone to support him/her, the government would bear the old age care responsibilities. The arrangement could take different forms. In cities, the employers would be responsible for the health care and pension for the elderly. For retirees with no family support, the employers or the local government at the residential neighbourhood level would arrange some forms of support through volunteerism (often by neighbours). A small number of the older people, often retired civil servants, would be eligible to live in homes for pensioners. In rural areas, elderly singles without any family support and income (sanwu renyuan, people with three "nos") would be supported by the village collectives. At the time, the Chinese population grew rapidly due to the government's encouragement of childbirth, hence the burden for old age care was typically shared among multiple siblings. Therefore, for the majority of the elderly at the time, the family was responsible for old age care and the state played a marginal role in providing elderly care.32 A large part of the state's role in elderly support in fact rested on the community or work-unit level, which included mutual help among colleagues from the same work unit and neighbours. Support from the work unit was, to some extent, considered to be at community level as state-owned enterprise employees tended to live in the same neighbourhood or in the vicinity of the employer-provided public housing.33

Such an analysis of the changes in old age care service delivery during the central planning era shows that the Chinese government clearly embraced a fixed mindset. In the 1950s, Chinese villages started a community cooperative system to offer care to all older people, but the system was unsustainable and the entitlement was narrowed to people without any kinship support and income. Private provision was forbidden during this period. Therefore the care responsibility for the majority quickly bounced back to adult children.34 [End Page 155]

SHIFTING TOWARDS A GROWTH MINDSET (1978–2010)

After 1978, the Chinese government embarked on an economic transition. It supported the privatisation of enterprises and most social services. The Chinese economy and society have experienced major changes since 1978. First, the shift from "central planning" to "market-oriented economy" aims to decentralise the highly centralised state power in the economy and society more to the private sector. Second, "seniority-based" pay shifted to "performance-based" pay that would reward people for achieving more based on performance indicators. The shift was evident in the introduction of performance appraisal centred around economic indicators in almost all sectors. Third, "relying on the state and on the work units" shifted to "self-reliance"—people could no longer expect employers to be responsible for employees' lifetime employment, social welfare provision and looking after retirees.

Paradoxically, economic transition had limited initial impacts on the delivery of old age care. Rather, it had played an important role in reinforcing the state's minimalist role which was a continuation rather than a departure from the past.

Since the 1980s, there was an emerging need for improvement in old age care. The average household size continued to decrease from 4.41 in 1982 to 3.96 in 1990, to 3.44 in 2000 and remained below 3.0 for some years until 2019.35 In the 2020 census, the average household size was 2.62, a dip from 3.1 in the 2010 census.36 The downtrend was a result of the One-Child Policy and the changing culture in living arrangements. Young couples became less inclined to live with their parents, and nuclear families became the norm.37 With the liberalisation of the labour market, a large proportion of the working population moved to different parts of the country and lived separately from their elderly parents.38 The erosion of community support after the economic reform aggravated the problems. Following the restructuring of many state-owned enterprises and housing reforms in the 1990s, social relationships among neighbours were no longer based on employment and long-term residence. People living in residential neighbourhoods today find that their neighbours are not their fellow colleagues from the same companies or decades-long neighbours.39 In cities, urban neighbourhoods became strangers' communities. In rural areas, young [End Page 156] people moved out of the villages, leaving behind the elderly and children. These changes challenged the traditional family care model, which relied heavily on the informal assistance provided by family members.

All these social changes required the country's responses to elderly care, since without them there would be a severe care shortage as population ageing continued. The Chinese government clearly recognised the risks and started to act. The problem was initially framed as "getting old before getting rich".40 However, the responses revealed the state's reluctance to bear more responsibilities. Such a fixed mindset could be examined from several perspectives:

Government's reluctance to take on more responsibilities

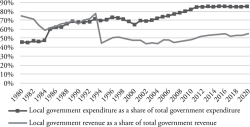

The central government was reluctant to take on the responsibilities following the decentralisation of fiscal power, which means the central government had handed a large proportion of the taxation and spending power to the local governments.41 Figure 1 highlights that after the 2010s, local governments accounted for over 80 per cent of total government expenditure and around 50 per cent of total government revenue.

Central–Local Share of Fiscal Revenue/Expenditure, 1980–2020

Source: CEIC database.

Government's insistence that adult children should be the primary care providers of the elderly

To address the growing incidences of elderly abuse and abandonment, the Chinese state enacted the Law for Protecting the Rights of Older People of the People's [End Page 157] Republic of China in October 1996. The law stipulates a legal obligation in China for children to care for elderly parents. The government also encouraged rural families to sign family support agreements, which would help clarify how elderly parents would be cared for. Parents could also turn to the court to demand their children to fulfil responsibilities based on this agreement. In this context, despite the social and economic transition in China's other sectors, past practices in the old age care sector had been reinforced and culturally defined moral family values were legally enforced. While these changes were often attributed to the return of the Confucian culture, they appeared to be well aligned with the era of relentless pursuit of economic growth and the "socialisation of social welfare", which witnessed a reduction in government spending on, but the private sector and families' increased role in, elderly care provision.

The focus on personal responsibility in financing old age care through social insurance contribution

Affordability has always been a key concern of policymakers. Social insurance was introduced to cover living costs (pension), health care (medical social insurance) and long-term social care (long-term care insurance) to protect people from risks and overdependence on the state. The underlying assumption of the social insurance system is that the system guides people to self-help. This is also in line with the pro-economic growth mindset underlying people's mindset that emphasises teaching people how to fish rather than give them fish. The focus on social insurance persists to this day.

As is evident in the care responsibility regulations and the financing of the pension system, the government had been reluctant to be directly responsible for old age care, and the implementation of new policies had pressured individuals and families into shouldering greater responsibilities. This is not to suggest that there have been no changes in the old age system since 1978. Major changes can be observed in the following areas.

Using the number of beds as policy targets

The central government indeed showed interest in addressing the issue of the underdeveloped old age care service system. It has focused on the ageing care development, targeting to increase the number of beds in care homes. In 2001, the target was to provide 10 care home beds for every 1,000 elderly people, and to provide care home services to 90 per cent of rural towns and villages. In the 2010–15 period, the target was to provide 30 care home beds per 1,000 seniors and this was increased to 30–40 beds per 1,000 seniors for the 2016–20 period.42 By the end of 2020, the total number of beds reached 8.075 million or 31 [End Page 158] beds per 1,000 seniors.43 The number of beds serves as a quantitative performance indicator for the higher authority to evaluate the performance of local officials in policy implementation. The indicator focuses on the physical assets rather than the human aspects of the service system, thereby encouraging investment in the "hardware" (e.g. beds, rooms, facilities) rather than in the "software" (e.g. service quality, labour skills) of the services. While this approach boosts infrastructure construction, the single-minded pursuit of increasing bed capacity as a priority for investment may result in an underinvestment in other resources required in the sector.

Following the setting up of public old age care institutions catering only to the privileged few who were mostly retired government officials, the Chinese government encouraged the private sector to provide the same for the general population. However, affordability remained a key concern. At the time, the private sector was not keen to provide old age care services for the elderly needing assisted living, having lost their capability of independence. Therefore, acute needs were not met. The government, unwilling to assume more responsibilities, continued to coerce adult children to provide care for their elderly parents. Nevertheless, the strategy was unsuccessful because adult children do not always live in the same cities as their parents. In affluent cities, such as Shanghai, ageing was the fastest among all cities in China. The old-age population was often higher than 50 per cent of the city's total population. To cope with the old age care problems, Shanghai had striven to provide state or private institutionalised care since 2007 for three per cent of the older population and community-based care for seven per cent of the elderly population, while the remaining 90 per cent of the older population would live in their current home as they aged. Other cities subsequently used this living arrangement. However, for many years, a national strategy to address the old age care issues has been lacking, apart from the bed capacity problem.

Since 2008, some cities had started to pilot home-based care support. To supplement what the institutional suppliers had provided, the idea was for the government to function as a coordinator to incorporate suppliers from different sectors to cover a wider range of services.

On the whole, the 1978–2000 period perpetuated the idea that children should be the primary caregivers of their elderly parents and the state should play only a marginal role. The state had indeed assumed some new roles such as introducing a social insurance system to force people to save more for old age and regulating family support. The state did not assume more care provider responsibilities due to the new roles but rather they had reinforced family support and self-help, which seemed to be a de facto continuation of the arrangement in the central planning era. As social changes had made the previous community mutual support difficult or impossible to sustain, the private sector, enabled by the marketisation reform, had partially filled the gap. In this sense, the state had a largely fixed mindset. The permission granted [End Page 159] private sector development is a patchwork reform to supplement the previous system of "family support plus minimalist state provision".

A Growth Mindset (2011–Present)

A real mindset change occurred after 2010 when the Chinese government decided to propel the old age care industry. To encourage private sector involvement and investment, the central strategy presented old age care as a new economic growth opportunity. Official documents often discussed ways to encourage seniors to "consume" old age care. More recently, economic terms such as "silver hair industry" or "silver hair economy" were increasingly used and became the new "green" or new "digital" future of the elderly care. The scale of the old age care economy was estimated to hit RMB13 trillion by 2030.44 This strategy aims to achieve several objectives. The pursuit of rapid economic growth could help accelerate the process and reduce the time taken between "getting old" and "getting rich". The focus on producing financial solutions could also better prepare people for old age care expenses.

Particularly through such a promotion of the private sector, the State Council introduced a comprehensive range of policies to boost the care industry. In February 2011, the Ministry of Civil Affairs issued the 12th Five-Year Plan for the Construction of the Social Old Age Service System, i.e. the "9073" Guideline for Old Age Care. The national guideline recommends that 90 per cent of old people would be cared for at home with social assistance, seven per cent would purchase community-based care services and three per cent would receive institutionalised care. In 2011, the State Council's Notice on the Construction Plan for the Social Old Age Service System (2011–2015) (Guanyu yinfa shehui yanglao fuwu tixi jianshe guihua [2011–2015 nian] de tongzhi) highlighted that community old age care services would be an important support for home care services comprising two components: community day care and home care support.45 The focus in urban and rural communities should be on day care centres, nurseries, activity centres, mutual support care service centres and other community care facilities, and the government should promote the development of comprehensive community service facilities to enhance old age care services. The goal is to increase the coverage of day care services to all urban communities and to more than half of rural communities. [End Page 160]

After the 12th Five-Year Plan period, the central government also increased its efforts to support social organisations through various public–private partnership agreements, such as public construction and private operation, entrusted management and contracted services. The government encouraged financial institutions to develop new financial products and services or provide subsidies or lower interest loans to attract private investors to enter the old age care sector. Ten ministries and commissions jointly published the Implementation Opinions on Encouraging Private Capital to Participate in the Development of the Elderly Service Industry (Guanyu guli minjian ziben canyu yanglao fuwu ye fazhan de shishi yijian). Meanwhile, the government also lowered the entry requirement and simplified administrative procedures for consecutive years between 2013 and 2018.

As a result of these efforts, two types of service models emerged in communities. One is the "B2B" (business-to-business) model in which the government pays for the construction of the care facilities and entrusts or funds the care institutions to provide home care services in the community. The other is the "B2C" (business-to-consumer) model whereby the service company directly provides services and collects service fees from customers or commercial insurance.

In 2012, the governments in several provinces and cities such as Shanghai, Chengdu, Jiangsu and Zhejiang began to introduce and set up community-based service centres that provide one-stop services to residents, including the elderly. The space for these set-ups could be indoors—where daycare centres, food halls and playrooms were located—or an open space in which older people could socialise and exercise. The corresponding services were provided by the local governments or private businesses. In some cases, local residents and the local community were encouraged to provide age care services by their own efforts. The government recently highlighted one such example, which is a mutual-help model of community-based aged care. Under this model, younger and fit seniors are expected to provide community care service in the local old age care facilities.46

These policy changes demonstrated a clear shift in the mindset at the central-government level. The state had stopped relying on the established policy framework and principles. It focused on policies directed at the actual delivery of services. In addition, care provision is no longer simply about family care and institutionalised care. Policymakers have also made a shift from ideology-driven solutions that promoted private finance to support private consumption towards more diverse state–provider relations, which the government clearly prefers. The providers could be from the private sector, working in collaboration with the state. This marked an obvious change to a growth mindset. The local governments are also allowed to conduct experiments that suit their local circumstances. [End Page 161]

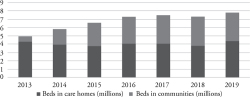

The changing mindset indeed has some effects. Figure 2 shows an uptrend in the number of beds, as monitored by the central government as a performance target for local governments. Community-based beds have, since 2014, grown at a much faster rate than the institutionalised services.

Bed Capacity in Care Homes vs in Communities

Source: Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People's Republic of China, China Civil Affairs Statistical Yearbook (2014–20).

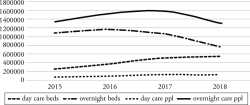

However, the growing number of beds should not be equated with successful service provision. First, the mindset shift at the centre did not happen throughout the system. In other words, the central government's shift to a growth mindset was not always matched at the local levels. For instance, the local governments and the private sector often did not see the benefit of developing community-based care and this had resulted in poor policy implementation. There had been many failed examples in the past: Starlight Project (Xingguang jihua, 2005), nursing homes (tuolao suo, 2013), rural mutual support happiness homes (nongcun huzhu xingfu yuan, 2012) and various forms of community care service organisations in different parts of the country. Moreover, despite the growing supply, community services do not seem to meet the needs of the users. Many overnight care facilities have had to be shut down since 2016 as there was insufficient demand (Figure 3). There was also a drop in the number of people in need of overnight care. Instead, the demand for day care beds continued to grow.

Table 3 shows the services that the elderly would require or need in the communities, and tabulates the proportion of communities that provided the services needed most based on 2015 data. Items marked with an asterisk "*" denote the types of services that the elderly said they would need the most. Data has shown that apart from health-care knowledge, health professional visits and legal services, all the other services are considered to have faced an undersupply. Even for services with a limited supply, there was a mismatch between the actual needs of the elderly and the available services. For instance, rehabilitation equipment is in high demand, but shops that stock such products and services are very few in the communities. There are usually only one or two designated shops in an entire city because policymakers view old [End Page 162] people requiring aged care products and services as consumers instead of essential users. The focus was on making profits from these products with rigid demand rather than providing convenient services for the people in need.

More Beds in Communities but Fewer Users

Note:

"ppl" in the data label means the number of users that have used the services.In this chart, the number of people using overnight care was larger than the number of beds. The reason is that not all people need to stay in the care facilities all the time and most people stay in these facilities for a few days just to give their children a break from caregiving.

Source: Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People's Republic of China, China Civil Affairs' Statistical Yearbook (2016–20).

Needed Services Reported by the Elderly and Percentage of Availability in Communities in China, 2015

A further analysis of the data in Table 3 and Figure 3 also reveals a more severe problem in community-based services. Day care centres are one of the most needed services, but the number of people using the facilities is low. A possible explanation is that seniors in need of day care cannot afford the services. It should also be highlighted [End Page 163] that although most communities do not even charge a fee for day care, the number of old people in need of the services in each community may not be large enough to sustain a fully operational service centre. As a result, day care centres have difficulty sustaining their businesses even with government subsidies. As discussed in some existing research, to save costs and secure government funding, the centres would rather provide more beds to obtain more government subsidies than pay better salaries to the care workers.47 A care worker receives an average wage of RMB3,000 to RMB3,500 per month. In the most affluent cities such as Shenzhen, a care worker's wage is about RMB4,600 per month. On the other hand, the costs of living and expected skills levels of the care workers in the affluent cities are also higher than in others. Maintaining the operations of these centres in all communities is extremely difficult. In addition, due to the relatively low income, people's willingness to work as a nurse or care worker is also low. It is not rewarding to work as nurses in hospitals or as hourly rated domestic workers who have to shuttle between many families each day. The shortage of care workers also means that existing care workers have a heavy workload and have to clock in unfriendly shifts.48 As a result, it is difficult to improve the quality of the labour force. According to data from the Ministry of Civil Affairs, there were more than two million old people living in 42,300 old age care homes by the second quarter of 2020.49 However, there were only 370,000 care workers, of which fewer than 200,000 were equipped with some professional training.50 The alarming truth is the number of people who had professional qualifications for old age care were about 40,000 in 2019.51 Besides, these qualified care workers almost exclusively worked in institutional care homes, and services provided in communities are often maintained by workers without any formal training.

DISCUSSION

The authors provide a comparison of the shift in mindsets over time and analyse the corresponding factors in Table 4. There are several characteristics of the transition [End Page 164] towards the growth mindset during the 1978–2010 period: for example, the market was introduced as a provider; and policies were introduced to strengthen the established notion that old age care should be primarily a family affair. The implementation of new policies and institutional arrangements, such as family support and the social insurance system, has indeed reinforced the care model that predominantly relies on children. Social changes, still ongoing, imply that maintaining family relationships, to most people, is difficult especially in an era of massive urbanisation where children do not live together with their parents. As a result, the state's minimalistic approach cannot be sustained.

Mindsets of the Government and Community-based Old Age Care in China

The shift towards a growth mindset at the national level has been obvious since 2011. At the time, the central government was willing to address the issues at the national level, introducing policy changes. The state not only decided to be more involved but [End Page 165] also attempted to involve society in elderly care. The focus of the reform showed a shift from financing old age care to delivery of care. New actors, such as social organisations and new policy instruments such as financial innovations were introduced. These solutions are not bounded by a narrow spectrum across political categories, i.e. family or market or state. Instead, a mixed system emerged, in which the family, market, community and the state each have a role to play. The state increasingly plays a coordinating and supporting role in facilitating innovative solutions. As is evident, the state–stakeholder relationship is no longer. The state is willing to lower the market entry barriers, introducing different forms of public–private partnership contracts or even providing subsidies. This means that the local-level governments would have a greater say based on local circumstances.

However, these changes have yet to bring about a boom of the community-based care sector. Several factors could have played a part in this.

• The mindset change at the central level does not guarantee a system-wide change. To motivate private players to come on board, the state had to resort to the discourse of economic growth. Such an approach, however, signalled to the local governments and service providers that old age care would be a new engine for economic growth, and that they might enjoy the same economic incentives as those in other policy areas, such as policies for special economic zones, social housing, infrastructure construction, small town construction and rural–urban integrated development. These other incentives resulted in a relentless pursuit of economic goals and growth. Yet old age care is not the same as those policy sectors. Also unlike social housing, old age care facilities do not have a return of investment value that housing assets would have. The opportunity costs of using land and housing for old age care is also high in residential neighbourhoods. As a result, the silver hair economy has not led to a booming health-care sector.

• The success of old age care depends heavily on user preference and affordability. The local governments continued to respond to their performance targets which are based on quantitative indicators such as bed capacity, the number of care homes and the number of users. This has caused an oversupply of beds but insufficient resources on training labour force and service quality improvement.

A growth mindset has been reflected in expansive growth in the old age care sector, i.e. more facilities are available. The growth is beneficial when there exists a greater demand for such facilities. However, due to the under-utility of certain aspects of care services currently, there is a need for a further mindset change. Not only the central and local governments but also the service providers have to adopt a growth mindset to detach themselves from the obsession with quantitative growth. Old age care, in particular community-based old age care is a complex social challenge that requires more nuanced thinking. Besides the consideration of the achievement of quantitative growth, the quality and types of services are important in meeting elderly needs, as people do have the option to stay at home. [End Page 166]

It should also be highlighted that communities in China have varying characteristics. The decisions on the type of services needed have to be informed by the users and not stipulated by the higher authorities. That is to say a benefit mindset is necessary at the service planning and delivery stage. Policymakers assuming a benefit mindset reach out to society and understand the needs of the users, and then deliberate the long-term solution to identify and address people's needs as shown in Tables 1 and 2. As population ageing is a continuous process and people's needs would also evolve with demographic changes, taking a long-term, future-proof perspective is relevant. Therefore, this calls for the shift to a benefit mindset in the long run to make the system adaptable to changes.

CONCLUSION

The fixed–growth–benefit mindset framework is useful for policy analyses. However, it needs to be operationalised in order to facilitate a comparative study of policies introduced with different mindsets. This article analyses the behaviour of the government through examining policy changes and the analysis could contribute to the literature on mindset theory in governmental policymaking in several aspects.

Governmental mindset transition is not simply a one-step at the top level of the government, even though such top-level changes may produce some positive results. To fully achieve the intended policy outcomes, systematic mindset changes, including vertically and horizontally coordinated changes, are needed. The mindset change also needs to happen across different perspectives of the policy field. For example, a policy formulated with a growth mindset would need an evaluation system with a growth mindset. Evaluators with a fixed mindset could become a constraint to the implementation of a growth mindset policy. In this sense, the capacity of top-level policy makers for a mindset change is only the first step towards the solution of a complicated policy issue.

Li Bingqin (bingqin.li@unsw.edu.au) is Professor and Director of the Chinese Social Policy Stream at the University of New South Wales. She received her PhD in Social Policy from the London School of Economics. Her research is on social inequality, social integration, policy analyses and governance.

Qian Jiwei (jiwei.qian@nus.edu.sg) is Senior Research Fellow at the East Asian Institute, National University of Singapore. He obtained his PhD in Economics from the National University of Singapore. His current research interests cover the digital economy, political economy, development economics and health economics.

Yang Sisi (sisi.yang12@gmail.com) is Sessional Academic at Macquarie University and Associate Investigator at the Australian Research Council (ARC) Centre of Excellence in Population Ageing Research (CEPAR) located in the University of New South Wales. She received her PhD in Demography from Macquarie University and the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Her research interests focus on issues related to migration, ageing and inequality, including the well-being of older adults, formal and informal settlement of migrants, migrant workers and employment, and health and inequality.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the East Asian Institute, National University of Singapore, for organising the international conference on "The Economic and Social Impacts of Population Ageing: China in a Global Perspective" which led to the publication of this article. Li Bingqin's work on this article was supported by the SHARP01 fund of the University of New South Wales.

Footnotes

1. Feng Zhanlian, Liu Chang, Guan Xinping and Vincent Mor, "China's Rapidly Aging Population Creates Policy Challenges in Shaping a Viable Long-term Care System", Health Affairs 31, no. 12 (2012): 2764–73.

2. Advisory Group on Issues and Response Strategies for Population Ageing in China, "Several Issues and Suggestions on Population Aging in Our Country", Bulletin of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, no. 5, (2002): 321–4.

3. See National Bureau of Statistics of China, at <http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/202105/t20210510_1817181.html> and <http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/tjgb/rkpcgb/qgrkpcgb/201104/t20110428_30327.html> [30 May 2021].

4. Wendy Dobson, "China's Incomplete Transformation, or What It Means to Age before Becoming Rich", in Partners and Rivals: The Uneasy Future of China's Relationship with the United States, Wendy Dobson (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2017), pp. 34–46.

5. Lauren Johnston, Liu Xing, Yang Maorui and Zhang Xiang, "Getting Rich after Getting Old: China's Demographic and Economic Transition in Dynamic International Context", in China's New Sources of Economic Growth, vol. 1, ed. Song Ligang, Ross Garnaut, Cai Fang and Lauren Johnston (Canberra: ANU Press, 2016), pp. 215–46.

6. Zhou Junshan and Alan Walker, "The Need for Community Care among Older People in China", Ageing & Society 36, no. 6 (2016): 1312–32.

7. Carol Dweck, Mindset: Changing the Way You Think to Fulfil Your Potential (updated edition) (Sydney: Hachette, 2017).

8. Inge Huijsmans, Ma Ili, Leticia Micheli, Claudia Civai, Mirre Stallen and Alan G. Sanfey, "A Scarcity Mindset Alters Neural Processing Underlying Consumer Decision Making", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, no. 24 (2019): 11699–704.

9. C. Clayton Childress, "Decision-making, Market Logic and the Rating Mindset: Negotiating BookScan in the Field of US Trade Publishing", European Journal of Cultural Studies 15, no. 5 (2012): 604–20.

10. Johanna Rahn, Alexander Jaudas and Anja Achtziger, "To Plan or Not to Plan—Mindset Effects on Visual Attention in Decision Making", Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics 9, no. 2 (2016): 109.

11. Ashley C. Buchanan and Margaret L. Kern, "The Benefit Mindset: The Psychology of Contribution and Everyday Leadership", International Journal of Wellbeing 7, no. 1 (2017): 1–11; Aaron Hochanadel and Dora Finamore, "Fixed and Growth Mindset in Education and How Grit Helps Students Persist in the Face of Adversity", Journal of International Education Research 11, no. 1 (2015): 47–50.

12. Oyvin Kyvik, "The Global Mindset: A Must for International Innovation and Entrepreneurship", International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 14, no. 2 (2018): 309–27.

13. World Health Organization, "Strategy on Health Policy and Systems Research: Changing the Mindset", 2012.

14. Buchanan and Kern, "The Benefit Mindset".

15. J. David Edwards, "Managerial Influences in Public Administration", International Journal of Organization Theory & Behavior 1, no. 4 (1998): 553–83.

16. Roseanne M. Mirabella, "Toward a More Perfect Nonprofit: The Performance Mindset and the 'Gift'", Administrative Theory & Praxis 35, no. 1 (2013): 81–105.

17. Karen Bogenschneider, Family Policy Matters: How Policymaking Affects Families and What Professionals Can Do (New York: Routledge, 2014).

18. Chrisna Du Plessis and Raymond J. Cole, "Motivating Change: Shifting the Paradigm", Building Research & Information 39, no. 5 (2011): 436–49; Mansour Javidan and David Bowen, "The 'Global Mindset' of Managers", Organizational Dynamics 42, no. 2 (2013): 145–55; Tae Kyung Kouzes and Barry Z. Posner, "Influence of Managers' Mindset on Leadership Behavior", Leadership & Organization Development Journal, no. 8 (2019): 829–44.

19. Lorenzo Duchi, Doug Lombardi, Fred Paas and Sofie M.M. Loyens, "How a Growth Mindset Can Change the Climate: The Power of Implicit Beliefs in Influencing People's View and Action", Journal of Environmental Psychology 70 (2020): 101461; Casey Wakai, "Do We Believe People Can Change? The Impact of Growth Mindset on Beliefs in Rehabilitation for the Earth and Incarcerated Individuals", 2020, at <https://scholarship.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/handle/10066/22702> [19 July 2021].

20. Mitchel Resnick, "Beyond the Centralized Mindset", The Journal of the Learning Sciences 5, no. 1 (1996): 1–22; Su Zhaohui, Dean McDonnell and Junaid Ahmad, "The Need for a Disaster Readiness Mindset: A Key Lesson from COVID-19", Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology (January 2021): 1–7; Ye Hailin, "India's Policy towards China under the Mindset of 'Assertive Government'", in Annual Report on the Development of the Indian Ocean Region (2015): 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, ed. Wang Rong and Zhu Cuiping (Cham: Springer, 2016), pp. 33–46.

21. Paul Bate, "Changing the Culture of a Hospital: From Hierarchy to Networked Community", Public Administration 78, no. 3 (2000): 485–512.

22. Meric S. Gertler and David A. Wolfe, "Local Social Knowledge Management: Community Actors, Institutions and Multilevel Governance in Regional Foresight Exercises", Futures 36, no. 1 (2004): 45–65; Zhu Xufeng, "Mandate Versus Championship: Vertical Government Intervention and Diffusion of Innovation in Public Services in Authoritarian China", Public Management Review 16, no. 1 (2014): 117–39.

23. Carol S. Dweck, "Mind-sets and Equitable Education", Principal Leadership 10, no. 5 (2010): 26–9.

24. Ibid.

25. Hochanadel and Finamore, "Fixed and Growth Mindset in Education and How Grit Helps Students Persist in the Face of Adversity".

26. Buchanan and Kern, "The Benefit Mindset".

27. Carol Dweck, "What Having a 'Growth Mindset' Actually Means", Harvard Business Review, no. 13 (2016): 213–26.

28. Buchanan and Kern, "The Benefit Mindset".

29. Allan McConnell and Paul 't Hart, "Inaction and Public Policy: Understanding Why Policymakers 'Do Nothing'", Policy Sciences 52, no. 4 (2019): 645–61.

30. Buchanan and Kern, "The Benefit Mindset".

31. Ka Ho Joshua Mok, Wong Yu Cheung and Zhang Xiulan, "When Marketisation and Privatisation Clash with Socialist Ideals: Educational Inequality in Urban China", International Journal of Educational Development 29, no. 5 (2009): 505–12; Wang Xiaolu, Fan Gang and Zhu Hengpeng, "Marketisation in China, Progress and Contribution to Growth", in China: Linking Markets for Growth, ed. Ross Garnaut and Song Ligang (Canberra: ANU Press, 2007), pp. 30–44.

32. Li Bingqin, Fang Lijie and Wang Jing, "Community-Based Social Service Delivery in China: Reshaped by Social Organisations?", paper presented at the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) Methodology Workshop New Directions in Social Policy, Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Li Bingqin, Fang Lijie, Wang Jing and Hu Bo, "Social Organisations and Old Age Services in Urban Communities in China: Stabilising Networks?", in Aging Welfare and Social Policy, ed. Jing Tian-kui, Stein Kuhnle, Pan Yi and Chen Sheying (Cham: Springer, 2019), pp. 169–209.

33. Chen Jie, Jing Juan, Man Yanyu and Yang Zan, "Public Housing in Mainland China: History, Ongoing Trends, and Future Perspectives", in The Future of Public Housing: Ongoing Trends in the East and the West, ed. Chen Jie, Jing Juan, Man Yanyu and Yang Zan (Berlin: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2013), pp. 13–35; Wang Yaping, "Public Sector Housing in Urban China 1949–1988: The Case of Xian", Housing Studies 10, no. 1 (1995): 57–82.

34. Chan Kwan Chak, Ngok Kinglun and David Phillips, Social Policy in China: Development and Well-being (Bristol: Policy Press, 2008).

35. National Bureau of Statistics of China, "Population Development Presents New Characteristics and New Trends in China", at <http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/sjjd/202105/t20210513_1817394.html> [13 May 2021].

36. National Bureau of Statistics of China, Communiqué of the Seventh National Census, no. 2, at <http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/202105/t20210510_1817178.html> [30 May 2021].

37. Gan Yiqing and Eric Fong, "Living Separately But Living Close: Coresidence of Adult Children and Parents in Urban China", Demographic Research 43 (2020): 315–28; Zhong Xiaohui and Li Bingqin, "New Intergenerational Contracts in the Making?—The Experience of Urban China", Journal of Asian Public Policy 10, no. 2 (2017): 167–82.

38. Song Qian, "Aging and Separation from Children: The Health Implications of Adult Migration for Elderly Parents in Rural China", Demographic Research 37 (2017): 1761.

39. Zhang Yunling, "China and its Neighbourhood: Transformation, Challenges and Grand Strategy", International Affairs 92, no. 4 (2016): 835–48.

40. Johnston, Liu, Yang and Zhang, "Getting Rich after Getting Old"; Zhong Shuiying, Zhao Yu and Ren Jingru, "Getting Old before Getting Rich in China: A Regional Perspective", Population Research 39, no. 1 (2015): 63.

41. Christine P.W. Wong, "Central–Local Relations in an Era of Fiscal Decline: The Paradox of Fiscal Decentralization in Post-Mao China", The China Quarterly 128 (1991): 691–715.

42. "Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People's Republic of China: By 2020, There Will be 40 Elderly Care Beds Per 1,000 Elderly People", Beijing Morning News (Beijing chenbao), 2014, at <http://www.chinanews.com/gn/2014/09-19/6607321.shtml> [15 July 2021].

43. The number of older people in 2020 was based on the 2020 population census, National Bureau of Statistics of China, Communiqué of the Seventh National Census, no. 2, at <http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/202105/t20210510_1817181.html> [30 May 2021].>

44. Zhang Xinpei, "New Care-Pension Model under the Background of the Combination of Medical Care and Pension Based on SWOT Analysis", Kitakyushu, 9th International Conference on Social Science and Education Research 2019, at <https://webofproceedings.org/proceedings_series/ESSP/SSER%202019/SSER30074.pdf> [20 July 2021].

45. The State Council Office, Notice on the Construction Plan for the Social Old Age Service System (2011–2015) (Guanyu yinfa shehui yanglao fuwu tixi jianshe guihua [2011–2015 nian] de tongzhi), Guobanfa [2011] No. 60, at <http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2012/content_2034729.htm> [15 July 2021].

46. He Xuefeng, "Mutual Support for the Elderly: The Way Out for the Elderly in Rural China", Journal of Nanjing Agricultural University: Social Science Edition 20, no. 5 (2020): 1–8.

47. Li, Fang, Wang and Hu Bo, "Social Organisations and Old Age Services in Urban Communities in China", pp. 169–209.

48. "Liudongxin da liubuzhuren yanglao huliyuanduiwu jipan shuxue" (Unable to Retain Aged Care Workers Due to High Mobility, Elderly Care Team in Need of New Bloods), Beijing Youth Daily, 3 September 2020, at <http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2020-09/03/c_1126446000.htm> [15 July 2021].

49. "Woguo gelei yanglaojigou yishouzhu laoren chao 210 wanren" (There Are Already more than 2.1 Million Elderly Residents in China's Different Types of Elderly Care Organisations), Xinhua News Agency, 29 July 2020, at <http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2020-07/29/c_1126301435.htm> [15 July 2021].

50. "Woguo Yanglaojigou Zhuanyehugong pubianduanque yanglaohulijigou weiheliubuzhu nianqinren?" (Why Are China's Elderly Care Organisations Able to Retain Young Workers When There is a Universal Shortage of Professional Care Workers?), China National Radio, 29 November 2020, at <http://china.cnr.cn/xwwgf/20201129/t20201129_525346169.shtml> [15 July 2021].

51. "Yanglao huliyuan yeyinggai shixian kuanjin yanchu" (Adopting the "Lenient Entry, Stringent Exit" Approach in Employing Elderly Care Workers), 18 October 2019, Beijing Youth Daily, at <http://www.xinhuanet.com/2019-10/18/c_1125119590.htm> [15 July 2021].