Family Letters

Falbel describes the process by which she and her brother and parents were saved from Austria on the eve of WWII through the determined efforts of an aunt and uncle in America, and subsequent failed attempts to obtain exit visas for her grandparents. Included are seven letters from among hundreds that were sent between family members in different countries, describing countless applications, petitions to embassies and aid organizations, as well as the arrests and round-ups that began to occur with increasing regularity.

When I was a child in the Bronx, there was an armoire in my room that had come with the rest of our belongings from the apartment in Vienna. Its large bottom drawer was almost inaccessible since the wood that had held the brass handles (which my mother still kept under the linens) had disintegrated. The handles, like the contents of the drawer needed to be saved because these objects were once owned and touched by people we had lost. I would open the drawer from time to time, mostly because of its inaccessibility. Among photographs of people and picture postcards of Alpine landscapes there was a [End Page 6] large box containing hundreds of handwritten postcards and a handful of letters in varied stages of decay. The correspondence was from my maternal grandparents Adolf and Henriette Schroetter.

It wasn't until many years later that I paid serious attention to these writings. The postcards and envelopes are imprinted with symbols and warnings, which illustrate how carefully the writers needed to phrase their messages. On the address side of each postcard, the censor's stamp announces in bold print: Gepruefft [examined]. The envelopes of the letters proclaim, Geoeffnet [opened] Oberkommando der Wehrmacht [High Command of the Wehrmacht]. At the center of each stamp, an eagle with outstretched wings perches atop a black-framed swastika that often obliterated some of my grandmother's writing on the side reserved for the "additional message." Their names on the return address also bore the added middle name "Israel" for men and "Sarah" for women, as ordered by the new laws for Jews.

A photograph identified on the back as taken in 1936 with a Jewish New Year's greeting to my father's relatives in Brooklyn, captures Adolf and Henriette Schroetter (everyone called her Jetti, pronounced Yetti), apparently on vacation, strolling down an avenue in Franzensbad, a famous spa in what was then Czechoslovakia. A second photo shows Adolf walking with my parents and my brother in a carriage in the Prater, a park not far from our apartment house in Vienna's second district, Leopoldstadt.

Other photos are of the dining room in our large, handsomely furnished apartment, and scenes of vacations in the mountains, lounging by a lake, all proof that "life was good," as my father used to say, much better in any case than his childhood in Zamarstyno'w, Poland, where his family lived apart from the dominant Polish culture.

The Zamarstyno'w of my father's youth was an industrial district literally across the railroad tracks from the main part of the city Lemberg (called Lwow when it was in Poland, Lvov when it was part of the Soviet Union, and is currently Lviv, Ukraine). The only photo of my paternal grandfather Josef Sigal is with his second wife Sheindl and their three children Henie, Moyshe and Sanek taken in a photo studio in Lemberg in January 1930.

My Hebrew name is from Josef's first wife, Chaya, my grandmother, about whom we know practically nothing except that she died in 1907, apparently during an influenza or perhaps typhus epidemic, leaving four children aged 10 (Anna), 8 (Chaim, my father), 6 (Herman) and 10 months (Isi). My father was known by three names, Chaim, Joachim, and Achim. It's complicated, as Jewish namings often are. His father and siblings called him Chaim because, being observant, they referred to each other by their Jewish names. Joachim was his "public" name, and, in Vienna, that's how he referred [End Page 7] to himself in business and in correspondence. Achim was a family name for him (short for Joachim). Married by a rabbi, Chaya and Josef had no money for the state's marriage certificate, so their children were declared illegitimate, and as the law decreed, bore the surname of their mother, Falbel.

The messages from the Schroetters, like lifelines from the waiting to be rescued to the rescued, crossed the seas somehow navigating the arbitrary eddies of bureaucratese to be delivered into our Brooklyn mailbox from August 1939, when we left Vienna, until the beginning of December 1941. My grandparents also wrote to Tante Hansi, my mother's cousin and only surviving relative, who left Vienna for Palestine in 1935. Those letters were given to me by her Israeli children.

My grandfather Josef Sigal wrote postcards in Yiddish. These were saved in an old suitcase by Uncle Morris and Aunt Anna, and came to me from their children when they moved to Israel. Anna was my father's sister whose unflagging efforts ultimately got us out of Austria. I also inherited some writings from my Aunt Gerda when she and my uncle Isi moved to assisted living from their Brooklyn apartment. "From your father who hopes to hear from you bsures toyves [good news]," is the way Josef Sigal always ended his writings.

I receive more of such correspondence to be translated from people who find boxes of it stored in their aging parents' closets—messages from parents to children, from brother to sister. Opening sentences expressed either joy at receiving news and sometimes photos, or anxiety at long periods of delay in mail delivery and the critical information, "We are healthy and hope you are also …" The final [End Page 8] sentences, "greetings and kisses and fond regards to …," named each of us, as if in the naming they could recreate our presence. Greetings were also added to the extended family, also naming each one so as not to forget, and perhaps not to be forgotten.

The excerpts below, organized chronologically, are chosen from the hundreds of pieces of correspondence documenting my parents' (Hansi and Achim Falbel) efforts to get us out after the Anschluss (1938-1939, addressed to Anna and Morris in Brooklyn and Tante Hansi in Palestine), and the efforts to get the Schroetters out (1940-1941, addressed to my parents).

This correspondence was literally a lifeline, until it was cut at the beginning of December 1941 with the U.S. entry into the war. The Schroetters wrote at least twice a week and often admitted, as in a postcard dated January 20, 1941, "According to habit, I am writing the postcard due for today, even though I still can't confirm having received either letter or postcard from you, nor has anything happened that is worth reporting." As time went on the frustration level increased since they were limited both by censorship and their fear of causing worry; consequently they often ran out of things to say. Until the very last letter, one senses hope of success that the Schroetters would find refuge with us in the United States.

The Letters

From Hans Silberstein (my mother's cousin by marriage) to Aunt Hansi in Palestine.

Vienna, August 15, 1938

I assume that you are current on the situation here; then you will certainly be able to draw the correct conclusions about the circumstances in which I will in a relatively short period of time find myself. You will have heard that many thousands of Jews have already left Vienna and you may think that the rest must soon follow, because ultimately, they would be unable to bear it materially or emotionally. Moreover they fulfill the wishes of the ruling circle who don't want the Jews and who also in every possible way make life here a misery for us. The Jews are today completely impoverished, those who formerly donated to the Jewish Cultural Community, must now beg that same agency for handouts, and this situation continues to get worse from day to day so that unfortunately there will be no more making a living in this community in the foreseeable future. Incomes have been cut, and it is only a question of how long they will be able to pay anything … [End Page 9] the world is turned on its head and nothing has become impossible.

Your Hans and Berta

Hansi and Joachim (Achim) Falbel to Anna and Morris in Brooklyn, NY

Vienna, 9th September 1938

Unfortunately nothing has yet changed about our circumstances, and because everything is closed, we have absolutely no prospect to get in anywhere. Therefore, our mood is not very rosy, as you can well imagine … As far as [Achim's] store is concerned, we are liquidating slowly but surely and, since he has given notice to vacate by the beginning of the month, we are moving the rest of the merchandise and equipment to the apartment. That way our expenses will also be somewhat less. As I wrote you the last time, I've completed a course in using a knitting machine, and since the result was very good, I've invested some of my savings in a knitting machine so that I'll be able to make clothes for us. Also, if we should succeed in getting out, it would be a good source of income. Further, I believe that if we would succeed in gaining entry, we would quickly be able to stand on our own feet. Dear Achim is also very clever and hardworking, and I also have skills for making money, whether by giving piano lessons or by knitting. But that depends first on having an entry permit. I think we would go to the moon if it were possible. Already two months ago, one of my friends left for Montevideo with her husband and children. Unfortunately, before we were able to obtain entry, Uruguay closed its doors to emigration. A second friend is leaving on October 6 to the U.S.A. with her husband and sister, and the third in our group already has a visa to Rio de Janeiro. So everyone disperses to all four winds, torn apart from each other, and glad that they can do it.

… The dear children are, thank God, well. Rita runs through the whole house and is for us all a ray of sunshine, since she thank God still doesn't understand. Gert is older and understands our circumstances exactly, demonstrated by his many remarks and questions. My heart always pains me that a child that really shouldn't have such worries has to rack his brains prematurely over things that are beyond him.

So, for today, I will close, because also Achim and Papa want to write. Write also a bit about your dear children. How they are and what they do. In a few days Gert is going to school and in fact, at the Jewish Council.

Let us hear from you soon again and be many thousand times kissed by your, Hansi

My Dears: From Hansi's writing, you can see the state of our lives. We have written to various aid organizations in Australia, Uruguay as well as New York about immigration, and they respond in form letters, that say "We are very sorry but…" It seems they don't really know our circumstances, even though we clearly wrote that we wouldn't be a burden to anyone. These organizations seem to exist for themselves and not for the refugees who need them. Please don't be angry that I write this way. It's just that at some point one loses control. I greet and kiss you as I do the dear children and wish you a happy New Year. Your Joachim

From Hansi and Achim to Anna and Morris in Brooklyn, NY

Vienna, 1. November 1938

Today I have so much to tell you that I don't even know where to begin. I don't know if you [End Page 10] read in the papers that starting on the 29. October, Poland has declared all Polish passports invalid. Following this nasty blow, on Thursday, the 27th, all foreigners in Vienna were arrested. You can imagine our terrible shock, when on Thursday evening at 8:30 Achim was simply taken away. The whole night long I waited on the hall stairs in case Achim came home, because they said he was taken only to validate his documents. The next day I found out that all those arrested were taken to the Rossauerlaende prison. Gerda called me to tell me that Isi had also been taken there. I went there to ask about Achim, but found out that it would take a week until I could get information about him. In a matter of days, all prisoners, including Isi were set free. Only Achim didn't come home. Not that night, nor on Saturday, or Saturday night. I was already half crazy, and it got worse when during that Saturday, word spread that all those with valid Polish passports were sent across the Polish border. On Sunday at 7 in the morning, the telephone rang—Achim was on the phone. I thought at first I was dreaming. But it was really Achim who called me from Neubenschen [Zbaszyn], on the Polish border and asked me to send him travel money immediately, because Poland didn't want to take the deportees. He also told me I could call him at a certain number in Neubenschen. Well, you know it didn't take me 15 minutes, and the money was already underway by telegraph. I also went to the Jewish Council to ask them to help those at the border without means. Afterwards, I called Achim at the number he gave me and found to my dismay that the group was again taken away. In fact, I found out from Achim afterwards that they were driven once more across the border, but the Poles sent them back again. But in the meantime the money that I sent had arrived and Achim and our neighbor and her daughter who were also there took the train home (he distributed the rest of the money to others, to get them as far as Berlin).

During those days I practically lived at the Jewish Council and made all the officials crazy. I'm already as well known there as a bad penny. On Monday, as I was coming home from another fruitless trek to the Council, Isi came towards me in the street and quietly told me that Achim had come home. In my joy at our reunion, I didn't stop to think, but then we looked at the other side of the coin. Achim told us that he had signed a document in the Rossauerlaende promising to leave Germany as soon as possible. Even in that moment when there was nothing so important as having him back, that news weighed heavily upon us, to have to leave and not to know where to go. We have already inquired everywhere, but at the moment there's not much that's hopeful. As dear God helps us out of one worry he throws us into another. Still I don't want to be ungrateful. It's only that I'm afraid they will come and arrest Achim again. I even thought, not without feeling conflicted, that if no other possibility exists, he could go alone somewhere in the meantime even though I don't know how and when we would see each other again.

So, Achim has decided to telegraph you tomorrow morning. I don't know if you can help us, but when in need, one clings to the smallest hope.

Greetings and Kisses Hansi

From Josef Sigal to Anna and Morris in Brooklyn, NY

B'H Lemberg May 15, 1939

I received your card and the 5 dollars. I thank you because you have revitalized me because I didn't have 10 groschen for shabes. It is very bad for me now; I don't have any livelihood. [End Page 11] Dear Moyshe worked in a factory until recently and now there is no work, and G. doesn't want to know me anymore. He gives me only 20 zlotes a month and I have 20 zlotes from health insurance and I have to live on that the whole month. I now need to pay 50 zlotes for the exam that Sanek has to take since he now finishes school. Maybe he will get a job. I am very upset that I have to write you such letters. I wouldn't have wished for an old age like this. I have already received 5 dollars from you three times. Dear Henie is upset because until now I haven't made her a wedding. What shall I do? I don't know what to do. Hashem should help me. Dear Herz and Itche have written to me that on May 7 they will leave Vienna for England and will write to me from there. I haven't received any further writing. Dear Chayim is supposed to go to Amerika some months later. We greet and kiss you all in our hearts. I kiss my treasured grandchildren,

your father Josef Sigal

From Josef Sigal to Anna and Morris in Brooklyn, NY

Postmarked sent Registered Lemberg 24/1941, Postmarked April 2, 1941 San Francisco, Postmarked April 6 and 7, 1941 Brooklyn, NY

Dear children, I wonder that I have not had any writing from you for a long time. Everyone here is Baruch Hashem well, and I hope to hear the same about you. Maybe it would be possible for you to ask if clothes and shoes could be sent, because they say you can send. The woman who told me that she received [things] from her mother when dear Herz wrote to her to ask how we are doing and why we don't write. I wrote already many times. Nothing more is new we greet and kiss you all with our hearts; we greet and kiss my treasured grandchildren,

your father who waits to hear from you all the best Josef Sigal

Greetings in Polish from Sanek

Also from Henie

From the Schroetters to Hansi and Achim in Brooklyn, NY

Vienna March 31, 1941

On the morning after sending my card … we received with joy your dear card … and in the evening as the Sabbath candles were burning, and, as every day, we sat with the household members around the table, suddenly the doorbell rang and I heard the call "Schroetter, Radiogramm." I knew right away, "That is from Hansi," and hurried to the foyer to receive it. Then I came back into the room, where with studied slowness, I opened the cover of the radiogram, while all eyes were fixed on my lips with fevered suspense and so I slowly read aloud, word for word: "Ships tickets paid, date and ship's name will soon be confirmed directly from the ships company to you and wired to the consulate. Hansi." … Unfortunately, this joy was diminished by the news of the death of Heinrich's mother after her happiness on learning that an affidavit was on the way for her and that she was looking forward to a possible reunion with her loved ones. The funeral was this morning. A second loss: Frau Jarolim, who maintained herself in the hope that she could possibly travel together with us died yesterday morning from a heart attack and was also buried this morning, because of which her sister Fr. Felberbaum suffered a stroke and was brought to the Rothschild hospital …

Papa and Apapa [End Page 12]

From the Schroetters to Hansi and Achim in Brooklyn, NY

Vienna, November 17, 1941

We are both still waiting even now for mail from you and we can only hope that the time of no mail will soon be at an end and that we will again receive news to lift our hearts and when possible with photos, which is truly necessary for us, because, like the weather, our mood is below zero, particularly, as some of our various acquaintances, also those who already have had their ship tickets in hand from the ship company, American Express, have received telegraphic notification, that the already paid for ship reservations, on the instructions of the subscriber were canceled, probably to use the money for something else. Besides, Hans told us yesterday that at the moment, transit through Cuba is not possible. We must also think about the possibility that our reunion will only remain a chimera, which dear God should prevent. Still, we are not alone in this situation, there are thousands of others like us and we must leave our future to dear God … Papa and Apapa

18/XI/41 This morning we received to our great surprise your cable from November 17, "Cuba visa submitted, if possible, take steps regarding payment of ship tickets and write immediately about it, kisses, Hansi." and we will accordingly with the help of Hans take the necessary steps, and also continue to keep you posted about how the matter proceeds …

Papa and Apapa [End Page 13]

Aftermath

Two weeks after being transported to Theresienstadt on September 10, 1942, on the first day of Sukkot, Adolf's already weakened heart gave out. Jetti's more defiant heart endured that same place for two more years; in July 1944, just after the Red Cross visited the camp and fell for the make-believe theater set the Nazi's staged for them, her 76-year old body had had enough.

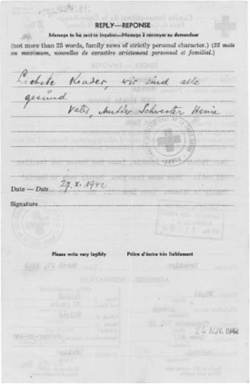

A message via the Red Cross was sent by my uncle Morris Brenner on April 3, 1942 to Josef Sigal, who was then living in the Lwow Ghetto.

My grandfather writes in response on 27. October, 1942 (it took over 6 months to get there), "Dear Children, we are all well. Father, Mother, Sister Henie."

There is no mention of his two sons, Moyshe and Sanek. It is notable that the instructions for such messages in both French and English, "not more than 25 words; family news of strictly personal character," do not allow for more than, "we are all well," even if they aren't. There was no further word; Josef, Sheindl, Henie, Moyshe and Sanek vanished and all attempts to find them after the war were in vain. [End Page 14]

Rita Falbel, born in Vienna, Austria entered the U.S. with her parents and brother 8 days before the war in Europe began in 1939. As a singer and songwriter she has presented programs of Jewish song throughout the U.S. and Israel. Her recordings—Hitchin' Rides, and Timepieces: Between Jewish Past and Future focus on the eclectic nature of Jewish musical expression. She is currently compiling and editing family correspondence for a book based on her translations from German and Yiddish of family correspondence from Vienna, Lwow and Palestine (1916–1947). She is one of the founding editors of Bridges.