Paradigmatic Chaos in Nuer

The case-number suffixes of the Western Nilotic language Nuer (Frank 1999) display a remarkable combination of formal simplicity and distributional complexity, which is manifested in: (i) a seemingly erratic form-function mapping that precludes attributing a consistent meaning to the suffixes, and (ii) a wealth of inflection classes only barely differentiated from each other. The suffixes looks as if they were rule-generated, but behave as if they were memorized. I advance a model of inflection combining principal parts, implicational rules, and default inheritance, in which the bulk of the complexity is attributed to the lexical stem, revealing the underlying systematicity behind suffix assignment.*

inflection, morphology, complexity, syncretism, inflection class, entropy

1. Case Syncretism and Inflectional Class.

Inflectional systems vary in the degree to which morphology imposes its own agenda on the realization of morphosyntactic values. For example, the mapping between case values and forms in Turkish nouns (Table 1a) is about as transparent as can be: each case value is realized by a distinct suffix, and these suffixes are the same for every noun (aside from the effects of vowel harmony). In German nouns (Table 1b), by contrast, the mapping is obscured by additional morphological peculiarities. First, they exhibit syncretism, in that for instance the nominative and accusative of 'heart' are identical (in fact, no noun actually distinguishes the full range of case values). Second, they fall into different inflection classes, in that the forms of the suffixes and their distribution are not the same for every noun. In spite of some considerable disagreement in the interpretation of such facts—some attribute them to underlying syntactic or semantic categories, while others point to them as evidence of autonomous morphological structure—there is a general consensus on the typological range of phenomena to be accounted for. While we know of systems like that of Turkish, with a straightforward mapping of functions to forms, and those like German, with greater morphological complexity, the full diversity of inflectional systems remains poorly understood, so we should not be surprised if we find facts at variance with our theoretical models. The noun paradigms of Nuer violate some basic assumptions about the nature of syncretism and inflection classes, and so suggest that some revisions to our notions of morphological structure are in order.

Morphologically transparent and opaque systems.

[End Page 467]

Nuer is a Western Nilotic language of South Sudan and neighboring parts of Ethiopia, most closely related to Dinka and Thok Reel (also known as Atuot), with around 800,000 speakers according to Ethnologue 16. Nouns in Nuer take suffixes for case and number. The suffix inventory is given in Table 2, adapted from Frank's (1999) study. There are two overt suffixes, -kä and -ä, used for the genitive/locative singular, and a plural suffix -ni. (The suffix -ni is consistently realized as -i after -l, -n, and -r; this phonologically regular rule has been factored out here and in all subsequent discussion.) In addition, any form may occur unsuffixed. 1

Suffix inventory of Nuer nouns.

On the face of it this is a very simple system. But consider how these suffixes are distributed in the paradigms of individual nouns, some examples of which are given in Table 3. With some lexemes the suffixes are restricted to a single morphosyntactic value; with others they are SYNCRETIC—that is, they combine two or more distinct morphosyntactic values in a single form. For example, -kä is used for the genitive singular of 'potato', but for the genitive and locative singular of 'bump'. While variation between syncretic and nonsyncretic distribution of morphological formatives is to be found in many languages, the sorts of patterns found in the Nuer paradigms are not ones that current models of morphology are well equipped to describe. There are two approaches that can be taken to account for the situation where a single formative has variable distribution: BLOCKING or EXTENSION.

Examples of Nuer noun inflection.

Blocking follows from the assumption that where multiple formatives are in competition, the more specific one is used. For example, in Latin the suffix -um has a potential distribution across two cases in the singular, the nominative and accusative (Table 4). This maximal distribution is seen with neuter nouns such as bellum 'war'.With masculine [End Page 468] nouns such as servus 'slave', it is found only in the accusative singular. But masculines have their own dedicated nominative singular suffix -us, so if we treat -um as underlyingly a nominative/accusative singular suffix, we can then say that its full range is blocked in masculines by their morphosyntactically more specific suffix -us. Conversely, where there is no obvious blocking environment, one can treat the syncretic distribution as derived. For example, in certain inflectional classes of the Russian noun, the suffix -a is found in the genitive singular with inanimates, and with both the accusative and genitive singular with animates (Table 5). If the nonsyncretic distribution with inanimates is treated as primary, the pattern with animates can then be attributed to the extension of the genitive form to the accusative, for example through a rule of referral (Zwicky 1985, Stump 1993).

Blocking (Latin nouns).

Extension (Russian nouns).

The Nuer patterns cannot consistently be described in terms of either blocking or extension. Consider the distribution of -kä and -ä in Table 6. Each suffix has a syncretic distribution, covering the genitive and locative (döl 'stone' and ca̱a̱r 'umbilical cord'). But each also has a restricted distribution: in mal 'peace' -ä is found in the genitive and -kä in the locative, while in puäär 'sky' it is the reverse. No combination of blocking and extension will systematically account for all four patterns. The only obvious option left over is to treat these patterns as the result of accidental homophony; thus genitive singular -kä 1 is distinct from locative singular -kä 2, and so forth. Syncretism would then simply be the cooccurrence of two homophonous suffixes in a single paradigm.

Erratic distribution (Nuer nouns).

There are two points that argue against this interpretation. First, the maximal distribution of the suffixes does correspond to a morphosyntactically coherent pattern, as seen in Table 2. If this were not acknowledged and, for example, -ni were treated as three homophonous suffixes, we have no account of why they line up neatly as 'plural', as opposed to any of the sixteen morphosyntactically disjunctive patterns that are also possible. Second, although accidental homophony certainly occurs in the languages of the world, in this case we would have to assume that the exact same accident befell every one of the suffixes (-kä, -ä, -ni, and zero), which strains credulity. This brings us [End Page 469] to the first question to be addressed in this article: Is there a way to characterize the 'coherence' of the patterns in Table 2, and at the same time the 'incoherence' of the patterns in Table 3, which seem to be two sides of one coin?

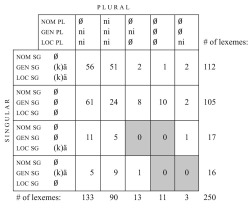

The unusual morphosyntactic distribution of the suffixes also has consequences for the structure of the lexicon. Based on Frank's (1999) corpus, the different paradigmatic patterns assumed by the suffixes yield twenty-four distinct inflectional classes, given in Table 7. (The class names are arbitrary.) One additional class (XXV) results from the aberrant appearance of -kä in the plural. 2

Complete inventory of suffixation patterns from Frank 1999.

But if these are inflection classes, they are inflection classes with a difference: they result from the seemingly unconstrained recombination of the same tiny set of suffixes. As normally construed, inflection classes are closely bound to allomorphy. Consider the Latvian case-number suffixes in Table 8. For any one morphosyntactic value there are from one to six allomorphs. Following a thought experiment from Carstairs 1983:117, these could in principle be mixed and matched to yield 230,400 classes (the product of the number of allomorphs for each morphosyntactic value). But in fact there are only seven classes, nearly the same as the maximal allomorphy in the system (the dative singular). Such observations led to the formulation of the principle of PARADIGM ECONOMY (Carstairs 1983), which has since undergone various reformulations and renamings (e.g. Carstairs-McCarthy 1994, Müller 2007).

The common thread behind these proposals is that inflectional paradigms have an internal structure, and are not simply a grab bag of forms jumbled together at random. But none of the concrete proposals match the data all that consistently. Thus the paradigm economy principle in its original version (Carstairs 1983) amounts to the claim that there should be one morphosyntactic value whose allomorphs should be sufficient to predict the behavior of the entire paradigm. In Latvian the dative singular almost fits the [End Page 470] bill, but not quite, as classes IIa and IIb remain ambiguous. Alater version, the NO-BLUR principle (Carstairs-McCarthy 1994), proposes that each affix either is specified as being unique to a particular inflection class, or is simply the general elsewhere default for the morphosyntactic value it realizes. Some parts of the Latvian paradigm conform to this (e.g. the accusative plural, where the suffixes -as, -es, and -is are unique to a single inflection class, and -us is found elsewhere), but others do not (e.g. the accusative singular suffixes -i and -u each range over multiple inflection classes).

Latvian case-number suffixes (Mathiassen 1997).

Of course, what is disproved by Latvian is triply disproved by Nuer, whose violations of paradigm economy are indeed massive. The problem with such constructs as paradigm economy and no-blur comes from trying to foist the burden of inflection class assignment onto one inflectional form. A system such as that of Nuer nouns, which has so few distinct suffixes and so many different suffix paradigms, shows that this is the wrong approach. Recent work on inflection classes has shifted the focus beyond this narrow restriction. One line of enquiry has revived the traditional notion of principal parts (Wurzel 1984, Finkel & Stump 2007, 2009), which are those parts of the paradigm sufficient to predict the entire paradigm. The paradigm economy principle and no-blur amount to a claim that one principal part will always suffice, but it is clearly the case that sometimes more will be needed. For example, in Latvian, while the dative singular is not sufficient to predict the entire paradigm for every item in Table 8, the dative plus the genitive singular is.

Another line of enquiry embraces the sum of the interrelationships between forms in the paradigm, assessed in terms of entropy (Ackerman et al. 2009). Entropy measures the degree of surprise—in the present context, surprise at the appearance of some form—and so provides a measure of predictability. For example, in Latvian, the genitive plural is always -u, so the degree of surprise at encountering a genitive plural in -u is low (zero); that is, it is 100% predictable. Conversely, there are six different dative singular endings, so the degree of surprise at finding -ai as opposed to any of the other five is rather high; that is, it is pretty unpredictable. Such raw entropy measures may be modified by considering additional information. In particular, the notion of PARADIGM ENTROPY (Malouf & Ackerman 2010) assesses how forms in a paradigm are able to predict each other. For example, while it may be hard to know whether the dative singular of some random Latvian noun will be -ai, if it is already known that its genitive singular is -as, then it becomes completely predictable, because the presence of genitive singular -as in the paradigm entails the presence of dative singular -ai (and vice versa, for that matter). Statistics may also be brought in as a factor that increases predictability (i.e. more frequent classes are favored). [End Page 471]

The notions of principal parts and paradigm entropy allow differences between inflection class systems to be described as a matter of degree, rather than simply as conformance or nonconformance to an inflexible constraint. By such measures, systems that appear on the face of it to differ by an order of magnitude can be shown to be similar in terms of their information structure. For example, Malouf and Ackerman (2010) show that the paradigm entropies of such different systems as Modern Greek nouns (with eight inflection classes), Arapesh verbs (with twenty-eight classes), and Chiquihuitlán Mazatec verbs (with over 100) are quite close (0.644, 0.6, and 0.709 bits respectively, where the range in their sample is from zero to 1.105). In all three languages the actual paradigm entropy is far lower than the logically possible extreme, the expected entropy (1.621, 4.071, and 4.920 bits, respectively). This discrepancy between expected entropy and paradigm entropy shows that there is some implicational network constraining the distribution of inflectional formatives into paradigms. The corresponding figures for Latvian are an expected entropy of 1.56 bits versus an actual entropy of 0.66, while for Nuer they are the expected entropy of 1.24 bits versus an actual entropy of 1.04 (calculated using Finkel and Stump's 'Analyzing principal parts' software). 3 Nuer's high figure for actual entropy, and the closeness of the figures for actual and expected entropy, show both that it is complex, and that the implicational network between the cells in the paradigm is weak. (Though note that when type frequency is factored in, the actual entropy is reduced to 0.87 bits.)

This brings us to the second question to be addressed in this article: Do the inflectional classes of Nuer have any structure, and if so, can we describe it? At first glance it does look as if there must be some constraints: the suffixes in Table 2 could in theory yield seventy-two inflection classes, but Frank's corpus yields evidence for only a bit more than a third of that. In §2 below I suggest that this restriction is partly a statistical accident—but with an emphasis on partly—and that there is indeed evidence for paradigmatic structure.

These questions are addressed as follows. First, the suffixation patterns are described in detail, and a brief overview of the stem alternation patterns insofar as they interact with suffixation is given. There are three major sources on Nuer noun inflection: Frank 1999, Crazzolara 1933, and Vandevort n.d. Each of these works describes a somewhat different variety of the language, however, so a presentation of all of the data at once would be hopelessly confusing. Therefore, descriptions are based on Frank's (1999) impressive study, which is the most comprehensive. (Data from other studies are adduced later in the article.) Next, a formal analysis (itself given in the appendix) of the paradigm-internal suffix patterns and the inflection classes is outlined, in which a key role is played by morphological indices. This analysis unites insights gained from work on morphological defaults, principal parts, and implicational rules. Finally, how these results fare with the patterns of noun inflection described in other studies of Nuer is examined, showing that, in spite of differences in detail, the same inflectional system is found.

2. Suffixes.

For all the freedom in the distribution of the suffixes, there is one line they do not cross: singular suffixes are distinct from plural suffixes (again, with the exception of class XXV). Therefore the task of describing the patterns will be made much simpler if we first look at singular and plural separately, and only then look at their [End Page 472] combination. In the singular (Table 9), out of nine logically possible patterns, all but one are attested. The dominant patterns by far are to have zero throughout, or to have -kä in the genitive/locative. The suffix -kä may also appear alone for either genitive or locative. The suffix -ä has the same distribution as -kä, but occurs with far fewer lexemes. Finally, there are mixed suffix paradigms with both -kä and -ä, in both of the possible combinations. Given these distributional generalizations, there is one logically possible pattern that is not attested, namely -ä in the genitive and zero in the locative. But given the relative rarity of -ä in the first place, and the fact that -ä does occur restricted to the genitive in another paradigm, there is no cause to see this gap as anything but accidental. Thus, within the singular the only hard constraint is that the nominative is always zero. There are, though, some clear preferences: syncretism of the locative and genitive, and choice of -kä over -ä.

Singular suffix patterns.

In the plural (Table 10), either -ni or zero is found for all of the cases. (Discussion of class XXV, with -kä in the genitive, is set aside until the end of §4.3.) As with the singular, there are two patterns that dominate: -ni throughout the plural, or only in the genitive and locative. Of the six remaining theoretically possible patterns, two are unattested in Frank's corpus, namely any pattern involving -ni in the nominative and zero in the locative. A simple near-exceptionless generalization now emerges: the presence of -ni in the nominative implies its presence throughout the plural. I leave the aberrant pattern (class XXIV) aside for the time being (see the end of §4.3). Thus, in contrast to the singular, there do appear to be structural constraints on the distribution of affixes in the plural: the suffix -ni may be used for any case in the plural, but if it used for the nominative, then it must be used everywhere.

Plural suffix patterns.

If we factor in these restrictions on plural suffixation, this reduces considerably the number of inflectional classes that we need to account for: in place of seventy-two there are now forty-five. This is still well over the attested twenty-three (i.e. the twenty-five listed in Table 7 minus the two aberrant classes XXIV and XXV). But there are no obvious principles that would account for the missing classes. In Figure 1 the patterns are arranged by the number of lexemes in the corpus. From this it is clear that the unattested paradigms would involve the combination of an infrequent singular pattern with an infrequent plural pattern, suggesting that the gaps are indeed a statistical accident. And in fact, eighteen of the twenty-two unattested classes would involve the singular suffix -ä, which is itself quite rare in the corpus.

However, even if there are no structural constraints on the paradigms, there are some singular-plural combinations that are less frequent than might be expected. To make this [End Page 473] clearer, in Figure 2 the effect of the rare suffix -ä has been factored out by combining it with -kä, yielding a number for 'overt singular suffix'. The first observation is that nearly all of the lexemes with zero suffixation throughout the plural have zero suffixation in the singular too (ten out of eleven). Second, class IV (zero in the singular and -ni throughout the plural) is noticeably underrepresented compared to the other three dominant patterns. In both cases I suggest below (end of §3.3) that these are by-products of the effect of stem alternations, and are not due to any constraints obtaining between the suffixation patterns themselves.

Tokens of singular and plural combinations in Frank's (1999) corpus (omitting aberrant classes XXIV and XXV).

Thus, paradigmatic distribution of Nuer case-number suffixes is surprisingly unconstrained; from the observations above only one firm rule emerges, namely that if the nominative plural is -ni, so is the rest of the plural. This reduces the complexity of the system, but not by that much. In addition, though, there are a number of tendencies that lend some predictability to the system, namely (i) the suffix -ä is infrequent, (ii) syncretism of the genitive and locative is generally preferred, and (iii) nouns that are zero-suffixed in the plural tend to be zero-suffixed in the singular as well. [End Page 474]

Same as Fig. 1, with the two overt suffixes of the singular conflated.

3. Stem Alternations.

Nuer nouns display a diverse set of stem alternation patterns that interact with suffixation, and so increase the predictability of suffixation patterns. It is not typically the case, however, that suffixation can be DIRECTLY predicted from the stem alternation pattern. On the whole, the two systems cross-classify. For example, Table 11 shows that in the singular nearly every attested suffixation pattern can occur with nonalternating stems (the two unattested combinations involve rare suffixation patterns, so this may be a statistical accident). In the plural (Table 12), all of the attested suffix patterns occur with nonalternating stems. This shows that the suffixation patterns do not depend directly on the stem alternation pattern. Conversely, a single affixation pattern may occur with a variety of stem alternation patterns (Table 13).

Singular suffixation patterns: most are independent of stem alternation.

Plural suffixation patterns: none are dependent on stem alternation.

A single suffix pattern found with various stem alternation patterns (represented as A-C).

[End Page 475]

The interaction of stem alternation patterns and suffixation reveals itself only through an inspection of their statistical distribution. In order to see this, some additional background on the system of stem alternations is necessary. The phonological and morphological diversity of the stem alternants is particularly rich, and the brief survey here cannot pretend to do it justice. However, there is no evidence that the phonological shape of stem alternations has any bearing on suffix assignment; rather, it is the paradigmatic patterning that plays a role. The discussion of the phonology of stem formation is accordingly brief.

3.1. Phonology of Stem Alternations.

Following Storch's (2005) classification, stem alternations involve: (i) vowel length, (ii) diphthongization, (iii) vowel quality, (iv) phonation type, and (v) stem-final consonants. In addition, suppletion is found with some lexemes (e.g. ciek ~ män 'woman ~ women'). The question of possible tonal alternations is a vexing one. Frank (1999) concludes that tone is not phonemic in the speech of his informant. Other sources do observe phonemic tone distinctions (Crazzolara 1933, Vandevort n.d., Yigezu 1995, Storch 2005), but only Crazzolara consistently provides tonal information for both number and case alternations. There is possible evidence that, even if there are tonal alternations in the variety described by Frank, they do not interact with suffixation patterns (see below §5.5). Therefore I set the issue of tone aside in this study.

The striking fact about most of the stem alternations is that they are 'reversible', as shown in Table 14 (compare column a and column b), so that there is no way to identify a stem as singular or plural in isolation. Lengthening can mark singular or plural, as can diphthongization, while the vowel quality alternations are analyzed by Storch (2005) as involving the opposition of two morphophonologically distinct vowel grades, 4 whereby grade 1 vowels can be singular or plural, as can grade 2. Storch characterizes the phonation type alternation as unidirectional, with breathy voice marking plural only, but Frank's material does contain some examples of the reverse (e.g. kuän 'food' in Table 14). Stem-final consonant alternations themselves are not reversible, but the stem-final consonants on their own are ambiguous, as shown in Table 15, where stem-final -th, -y, and -Ɣ may all be found in both the singular and the plural. (All of these consonants may occur as nonalternating stem-final segments as well.)

Reversible stem alternations for number.

Examples of stem-final consonant alternations for number.

[End Page 476]

These patterns can be traced back to a common Western Nilotic system of tripartite number, in which there were three ways of marking number distinctions: overt marking of the singular, overt marking of the plural, or both (Corbett 2000:156-59, Dimmendaal 2000, Storch 2005). Some languages (such as those of the Luo group) preserve the original system in which the marking did indeed consist of overt suffixes, but in Nuer these have become fused to the stem, having left their traces via such processes as compensatory lengthening, regressive ATR harmony (now realized as the phonation type alternation; Andersen 1990:18-19), or, in the case of consonantal suffixes, stem-final consonant alternations. Thus wum 'nose' would represent an unmarked singular whose plural is marked by lengthening, and tut would represent an unmarked plural whose singular is marked by lengthening. It remains controversial to what extent tripartite number marking can still be seen as a coherent system in a language such as Nuer. Some researchers emphasize the functional continuity across this group of languages, even where the morphology has become obscured (Dimmendaal 2000); others emphasize the morphological unpredictability of the forms (see Gilley 1992 on Shilluk, and Ladd et al. 2009 on Dinka). The original semantic motivation is recoverable to some extent; for example, nouns with unmarked plural stems can typically be seen as once having had a collective or mass interpretation (see the examples in Storch 2005:204-6). But whatever its status, the suffixation patterns that are the focus of this article appear to be indifferent to the distinction between marked and unmarked stems. For example, overt plural suffixation can apply to both: compare bap ~ baap-ni 'front of body.SG~PL', with a marked plural stem, and määth ~ mäth-ni 'friend.SG~PL', with an unmarked plural stem. It should also be emphasized that this system has no bearing on the morphosyntax of number agreement, which is strictly singular ~ plural.

Stem alternations for case involve similar patterns to number alternations, except that suppletion does not occur. Vowel length, diphthongization, vowel quality, and phonation type alternations all occur, both with and without overt case-number suffixation. Stem-final consonant alternations, however, appear to preclude overt suffixation. And as with number marking, most of these alternations are 'reversible', as shown in Table 16, illustrating the opposition of the nominative and locative singular, unless otherwise noted. As with stem alternations for number, it is not possible to predict the morphosyntactic value from the type of stem alternation. In addition, there appear to be some nonreversible alternations, namely modal ~ breathy voice (nhim ~ nhim-kä 'hair.GEN.SG~LOC.SG'), and stem-final consonant alternations (kaw ~ kath 'chest.GEN.SG~LOC.SG').

Reversible stem alternations for case.

The origins of the stem alternations for case are less clear than the number alternations. Among other Western Nilotic languages, Dinka has a locative (actually, two locatives) marked by stem-vowel alternations that show a family resemblance to the Nuer alternations (Andersen 2002), but lacks stem-final consonant alternations. Thok Reel, the closest relative to Nuer, displays similar stem alternations for the genitive and locative, but these have yet to be fully investigated (Reid 2010). Given the similarities between stem alternations for case and number, it is likely that similar processes were originally involved, namely a period of suffixation followed by phonological changes. [End Page 477]

3.2. Patterns of Stem Alternation.

Some examples of different stem alternation patterns are shown in Table 17. This is just a small sample: the stem alternation patterns are no less complex than their phonology, with the nouns in Frank's corpus displaying up to five distinct stems, 5 falling into forty-eight different patterns. Nevertheless, some patterns emerge as dominant. Frank proposes (1999:26) a semi-hierarchical model of stem organization in which the (i) nominative plural is based on the nominative singular, and (ii) the genitive/locative is based on the nominative. 6 Nonalternation is also an option, and is in fact the default, at least for nonce items (Frank 1999:21-23). This yields eight basic patterns accounting for 74% of the lexicon (186 lexemes), illustrated in Figure 3. The remaining patterns result from a further subdivision of the genitive/ locative stem into distinct genitive and locative stems (these are indicated by dotted lines in Fig. 3).

Some examples of stem alternation patterns (represented as A-E).

Basic stem alternation patterns (following Frank 1999).

While this model gives a useful picture of the major principles of stem organization, it does deviate noticeably from the surface facts: only 151 lexemes (61%) display stem alternation patterns that perfectly match those shown in Fig. 3. Therefore, in the following discussion I consider only the surface distribution of forms, retaining, however, the fundamental insight of Frank's model, namely that stem alternations primarily involve number, and within number, case. It is these oppositions that play a role in suffix assignment (discussed in the following section) and also characterize the most common (surface) patterns, exemplified by the first two types illustrated in Table 17 (kεw 'gazelle' and luɔ̱t 'shirt'), which together with nonalternating stems account for 123 lexemes (49% of the lexicon).

3.3. Interactions Between Stem Alternation Patterns and Suffixation.

Let us first consider stem alternations for number. Here the stem alternations have quite a noticeable [End Page 478] effect on suffix distribution. Recall from Table 7 that there are two predominant plural suffix patterns that are in competition: -ni throughout the plural, and -ni only in the genitive/locative. To a large measure the choice can be predicted from the presence or absence of a stem alternation. Where the stem does not alternate for number (Table 18a), -ni suffixation is virtually obligatory (there are two exceptions). This obligatoriness of -ni suffixation with nonalternating stems looks as if it may be motivated by avoidance of homophony with the corresponding singular case, particularly in the nominative, where no overtly singular suffix is available to effect disambiguation. Zero suffixation is thus possible only where there is a stem alternation (Table 18b). Surprisingly, this reveals a sharp distinction in the treatment of the nominative and genitive/locative, even though it is the same 'plural' suffix that is involved: -ni suffixation is strongly preferred in the genitive and locative (91% and 88%, respectively), and almost as strongly dispreferred in the nominative (15%).

Plural suffixation correlated with stem alternation, showing number of lexemes (numbers derived from counting within each case separately, across all lexemes).

Stem alternations for case have a less categorical effect on suffix patterns; to make this clearer, the two allomorphs -kä and -ä have been conflated in Table 19. In the singular, there is a weak complementarity between stem alternation and suffixation: nonal-ternating stems are more likely to have overt suffixation in both the genitive and locative (72%), while alternating stems are more likely to have zero suffixation in both the genitive and locative (66%). (The behavior of lexemes that have overt suffixation only in one singular case is unclear: the numbers are given in Table 19, but are too low to interpret.)

Singular suffixation correlated with stem alternation, showing number of lexemes.

This implicational relationship between singular stem alternation and suffixation may then account for two phenomena observed above in Fig. 2. The first is the relative infrequency of class IV, which has zero in the singular and -ni throughout the plural. Since roughly one third (thirty-six of ninety) of the lexemes with -ni throughout the plural are ones with completely invariant stems, these will tend not to have zero suffixation in the singular. The second is the fact that zero suffixation in the plural typically implies zero suffixation in the singular. Such nouns invariably have a stem alternation in the singular, and thus will tend to have zero suffixation. [End Page 479]

In sum, there are two respects in which stem alternation patterns influence case-number suffixation: (i) if the stem is invariant for number, -ni suffixation in the plural is (practically) obligatory; otherwise, the default pattern is to have -ni suffixation in the genitive and locative plural only, and (ii) if the singular stem is invariant, overt suffixation in both the genitive and locative singular is preferred, while if the singular stem alternates for case, zero suffixation is preferred. These are important observations, because they show that Nuer case-number suffixation is not as unpredictable as previous work has suggested. Thus Frank identifies a single default suffixation pattern (our class III), with -kä in the genitive/locative singular and -ni throughout the plural, and treats the remaining patterns as irregular, which leads to the surprising observation that 82% of the lexicon (207 lexemes) has irregular suffixation. If default suffixation is instead seen as sensitive to the morphological context—that is, the stem alternation pattern— this figure is reduced to 57% (145 lexemes). Seen from this perspective, the degree of irregularity in the Nuer system is comparable to that found in other languages with inflectional classes. For example, Russian nouns fall into four major inflection classes. One of these (masculines with a zero suffix in the nominative singular) is arguably the default, accounting for 47% of the lexicon (Brown et al. 1996:57, citing Zaliznjak 1977), meaning that 53% of the lexicon displays irregular suffixation.

4. Analysis of Nuer Case-Number Suffixation.

Nuer case-number suffixation poses two analytical challenges. The first is to account for the polyfunctionality of the suffixes, whose patterns of syncretism cannot be systematically described in contemporary morphological models. The proposal advanced here involves a two-tiered concept of morphological exponence, in which the licit and actual range of a morphological formative are defined separately. The second challenge is to account for the inflection classes that the variable suffixation patterns divide the lexicon into. These are not inflection classes in the normal construal of the term, since, except for the opposition of genitive/locative singular -kä and -ä, they are not characterized by allomorphic differences. The proposal advanced here involves incorporating the various statistical tendencies and implicational relationships described in §2 and §3 into the inflectional rules themselves.

The analysis is framed in informal terms, in order to highlight the linguistically important generalization, but it has also been formally implemented as a NETWORK MORPHOLOGY analysis (Corbett & Fraser 1993, Brown & Hippisley 2012) in DATR, a lexical knowledge representation language that has the advantage of simplicity and computational testability (Evans & Gazdar 1996). The viability of the system of inflectional rules and the shape of lexical entries described in the following sections have thus been confirmed (see appendix).

4.1. Suffixes and Syncretism.

The normal understanding of inflectional rules is that they involve a static mapping between morphosyntactic values and phonological form. This may be further manipulated to yield varying patterns of distribution. As discussed in §1, this entails a restrictive theory of what patterns are possible. Table 20 illustrates the range of choices. In Table 20a, the rules for lexeme I state that form x realizes value 1 and form y realizes value 2. In lexeme II the form that realizes value 1 is extended to value 2 (e.g. by a rule of referral or impoverishment). In Table 20b an inflectional rule identifies form x as ranging over values 1 and 2 for lexemes I and II. A second rule states that form y realizes value 2 in lexeme II, and a third rule states that form z realizes value 1 in lexeme III. These more specific rules block form x in a portion of its range.

The effect of these types of analysis is that form x has variable distribution in the paradigm, but with certain restrictions. Under an extension analysis the form must be anchored [End Page 480] to some cell in the paradigm—in Table 20a, form x is introduced into the paradigm under value 1, and then extended beyond that. Under a blocking analysis, there needs to be some overt blocking form—y and z in the case of Table 20b. What is NOT permitted under either analysis is the variable distribution of a form where (i) the form is not anchored to any particular cell, and (ii) there is no associated blocking form. This is schematically illustrated in Table 20c, where forms x and y have the same variable range: they can realize value 1 or value 2, or both. Neither form can be uniquely associated with either value, so neither an extension nor a blocking analysis is possible.

Variable distribution of forms in paradigms.

The problem with current approaches is that these operations are construed as operations on phonological forms. The solution, I suggest, is instead to channel the inflectional rules through an abstract morphological index, which allows us to define the potential range of a form without actually having to insert the form into the paradigm. By convention I represent morphological indices with SMALL CAPS; as a mnemonic their names correspond to the phonological form of the suffixes they license. As a preliminary, in 1 the mapping from index to phonological form is given.

-

1. Mapping of morphological index to phonology

a. KÄ has the form -kä.

b. Ä has the form -ä.

c. NI has the form -ni.

d. ZERO is the absence of a suffix.

The permissible distribution of the suffixes is defined in 2. Note that the generalization that the nominative singular is always zero emerges from the fact that no other affix is licensed for this value.

-

2. Permissible distribution of the suffixes

a. KÄ or Ä are allowed in the genitive and locative singular.

b. NI is allowed in the plural.

c. ZERO is allowed anywhere.

But it should be stressed that the distribution of forms in the morphological paradigm is the work of the inflectional rules and lexical entries: they identify which portion of the licit range is actually exploited by the suffixes. The following sections describe how this functions.

4.2. Inflection Rules and Variable Defaults.

The suffix paradigms of Nuer nouns are divided into a number of inflectional classes largely characterized by variations in the distribution of the forms. And while it is remarkable how freely the different possible configurations are recombined, there are nonetheless significant restrictions and statistical preferences, as shown in §2 and §3. The inflectional rules should capture both of these, by establishing an implicational network and by introducing a set of defaults that are variable in the sense that they are contingent on this implicational network. The inflectional rules in 3-5 recapitulate the observations made in §2 and §3. First, there are some global default rules. [End Page 481]

-

3. Global rules

a. By default, genitive and locative singular are KÄ.

b. By default, genitive and locative plural are NI.

c. By default, nominative plural is ZERO.

Next, there are some rules that are dependent on the suffixation found in other parts of the paradigm. The first of these is so close to being exceptionless that it is treated as categorical; any exceptions are handled by the extraordinary means outlined at the end of §4.3.

-

4. Suffixation-contingent rules

a. If the nominative plural is NI, this entails NI in the other plural cases.

b. By default, genitive and locative are identical.

Finally, there are some rules that are conditional on the stem alternation pattern. Again, the first of these is treated as categorical.

-

5. Stem-contingent rules

a. If the plural stem and the singular stem are identical, this entails that the plural is NI.

b. By default, if the singular displays a stem alternation for case, genitive and locative singular are ZERO.

What sorts of paradigms result now depends on the lexical entry.

4.3. The Lexical Entry and Morphological Indices.

The lexical entry contains information about the stem alternation pattern (assumed here to be a given) and suffixation, expressed in terms of morphological indices. An entry can contain up to four morphological indices (six are logically possible but would have no effect on the outcome), 7 which specify exceptions to the default pattern dictated by the inflectional rules. In Table 21 the effects of stem alternation by itself are illustrated. In Table 21a, the stem is nonalternating, and so by default takes -kä in the genitive and locative singular, and -ni throughout the plural. In Table 21b, the stem alternates for case and number, and so by default takes zero in the singular and nominative plural, and -ni in the genitive and locative plural. Note that neither noun has a morphological index in its lexical entry, the differences being entirely due to differences in the stem alternation pattern.

Variable defaults dependent on stem alternation pattern.

[End Page 482]

The use of indices to effect overrides of the default is illustrated in Table 22. In the first example ('mouse'), -ä is found in place of -kä in the genitive and locative singular. The lexical entry encodes this with the index 'Ä'. Note that the index can be associated with either the genitive or locative: genitive/locative syncretism is construed as bidirectional, so any exceptional specification for one will be propagated to the other. In the second example ('monkey'), default syncretism must be overridden in the singular, so both cells are lexically specified with a morphological index. In the plural, the default rule stipulates that the nominative plural is zero, so long as there is a stem alternation for number (as seen with 'crocodile' above); this too must be overridden.

Example of lexically specified morphological indices.

Note that there are no actual constraints on the distribution of morphological indices in the lexical entry—anything not sanctioned by the rules in 1-5 is simply ignored (on truly exceptional patterns, see the end of this section).

We can now use the shape of the lexical entry to model the distribution of inflection classes across the lexicon. Since lexically specified morphological indices mark exceptions to the default pattern, if we construe 'default' as 'frequent' and 'exceptional' as 'infrequent', and if the inflectional rules have been correctly formulated, then a low number of indices should correlate with high type frequency and vice versa. And this is what we find in Frank's (1999) corpus. First, there are 107 lexemes that require no morphological index at all; that is, they display default suffixation. Note that this is quite a different view of default suffixation from the one given by Frank. In his analysis, there is a single default pattern (class III), found with only forty-five lexemes. In the present analysis, there is no single default: because the rules are sensitive to stem alternation, there are four default patterns, thereby covering a larger portion of the lexicon. The remaining patterns require one to four indices, covering increasingly smaller portions of the lexicon: eighty-three lexemes require one, forty-six require two, eleven require three, and just two have four. The breakdown by inflectional class is given in Table 23. At a gross level of generalization, we can observe that the four largest classes have an average of less than one index per lexeme, while classes with an average of three or more indices have only one member each. 8

In addition, there are three lexemes with truly exceptional behavior, noted as 'aberrant' in Table 23. But even here the Nuer suffix system is constrained, because the exceptionality is in the distribution of the forms rather than in the phonological shape of [End Page 483] the forms. Here we can have an exceptional rule that still makes reference to the indices as given in 1, but overrides the distributional constraints in 2. This formalizes the generalization that there are no exceptional suffix forms in this system, only exceptional distributions.

Number of morphological indices per inflection class (showing number of lexemes, except in final column).

4.4. The Nature of the Morphological Indices.

The morphological indices that play the central role in the analysis perform a double function, serving both as a means to represent paradigm-internal patterns (syncretism) and paradigm-external relationships (inflection classes). They do so by combining and adapting several ideas already in circulation in the morphological literature. In the description of syncretic patterns, indices have been used to model the separation of morphological form and paradigmatic distribution (Baerman et al. 2005, Bonami & Boyé 2010, Spencer 2010; see also discussion in Blevins 2006). The novelty of the present analysis is the layer of distributional constraints in 2, which license the forms for a particular grammatical meaning or set of meanings, without actually assigning them these meanings. This allows for a formalization of the equivocal patterns that the Nuer suffixes display; that is, they have both a global and a local meaning.

In the description of inflection classes the morphological indices bridge the gap between inflection class features and principal parts. Inflection class features are a morphological index that points directly to the inflectional paradigm. Principal parts are a [End Page 484] concrete version of this, with inflection class membership deduced from some set of forms stored in the lexical entry. The present analysis combines the two by using indices that serve as principal parts. These are indices in the sense that they still need to be interpreted by the rule set, but at the same time represent the minimum of what must be stored in the lexical entry. (There is of course no need to rule out storage of more than the minimum, as might be justified in the case of items with high token frequency.) In so doing, the model formalizes the distinction between stored information that has implications for other parts of the paradigm, and stored information that is simply exceptional, a systemic dead end, corresponding to the distinction between predictive and nonpredictive principal parts (Finkel & Stump 2007:62).

5. Comparative Observations.

Although the other sources on Nuer noun inflection are not as comprehensive as Frank 1999, they provide a confirmation of the main lines of the analysis in §4. Crazzolara (1933) includes the complete paradigms of 219 nouns in his grammar, while Vandevort's (n.d.) field notes, compiled in the 1950s and early 1960s, provide at least partial paradigms of several hundred nouns, from which at least the nominative and genitive in both numbers can be recovered for 305 nouns. 9 Each of these three works describes a different variety (or dialect) of the language, and hence there are considerable differences between them. It is therefore all the more striking that the main principles governing the system are much the same. The comparison below is in two parts. First, the varieties' behavior with respect to the inflectional rules in §4 is contrasted. Here additional sources on Nuer (dictionaries and word lists) are adduced where appropriate. Second, the inflectional behavior of cognate items is compared. This turns out to correspond for the majority of items, which confirms that the rules are not ephemeral—the lexical specification, as encoded in the morphological indices, is diachronically quite stable.

5.1. The Form of the Suffixes.

All three varieties have the same inventory of suffixes. The major difference is that in the variety described by Crazzolara, -nä is found in place of the -ni described in other sources; he notes that -nä is a characteristic of western dialects (1933:8). The allomorphy of -ni/-nä is likewise the same in all three, with n deleted following l or r. 10

The allomorphic distribution of -kä versus -ä varies widely, though as shown below, the overall inflectional generalizations appear to be indifferent to this. In Frank's description -kä is the dominant allomorph, with -ä found in just a handful of lexemes (133 vs. nine nouns, plus five nouns with both). In the variety described by Vandevort the reverse is true (135 nouns vs. five nouns, plus six that display variation), while in Crazzolara's material -kä is even more restricted, found only with verbal nouns formed from the (sometimes) auxiliaries tää 'stay' and wää 'go' (Crazzolara 1933:81, 94). The data from Kiggen's (1948) dictionary match Crazzolara's data in this respect, and include a few additional items, likewise all vowel-final. In addition, both Vandevort and Crazzolara provide information about demonstrative and interrogative pronouns, some of which inflect for case. In contrast to most nouns, these are invariably vowel-final, and [End Page 485] take -kä in the genitive/locative, for example, nεmε-kä 'this-GEN', titi-kä 'these-GEN', 11 nŠmŠ-kä 'that-GEN', ŋu-kä 'who?-GEN' (Vandevort n.d. lessons 8, 10, 12; the last is found in Crazzolara's material as well).

Huffman's (1929) and Stigand's (1923) dictionaries provide further evidence for variation in the allomorphic distribution of -kä and -ä. Although they do not contain paradigms, many of the entries do contain inflected forms. Stigand's material matches Frank's, with the equivalent of -kä (see n. 10) found in all ten entries where an overt genitive singular suffix is given (one example following a stem-final -k is ambiguous). And Huffman's material, interestingly, represents an in-between state: where an overt genitive singular suffix is listed, thirty-one entries have -kä, twenty-five have -ä, and three show variation.

5.2. The Functions of the Suffixes.

The suffixes have the same functions in all three varieties: -kä and -ä are used in the genitive and locative singular, and -ni/-nä in the plural. The one notable exception are two nouns in Crazzolara's material for which -nä is found in the singular, for example, karai 'field.NOM.SG', karai-nä 'field.GEN/LOC.SG'.

5.3. Syncretism of the Genitive and Locative Suffixes.

In Frank's material syncretism is typical, but not obligatory: it is found in 215 lexemes in the singular (85% of the corpus) and 235 (93% of the corpus) in the plural. In the varieties described by Crazzolara and Vandevort, syncretism of the suffixes appears to be obligatory, or nearly so. Instances of distinct genitive and locative forms all involve stem alternations under zero suffixation. But since neither author states whether this is the case, and since Vandevort's field notes seldom list all six forms, it is not certain whether syncretism is really obligatory or merely predominant. Vandevort's field notes contain one lexeme where the suffixes are distinct, a plurale tantum noun meaning 'milk with këëth (steer urine)': nahk 'NOM/LOC.PL', nahk-ni 'GEN.PL'. Kiggen's (1948) dictionary contains a few examples in the singular, either with -ä in the genitive and zero in the locative (nath '(Nuer) man'), or vice versa (tŠŋpiny 'groundnut'). 12 Thus, although there is evidence for the range of classes found in Frank's description, for the purposes of comparison we are largely restricted to those six inflection classes in which genitive and locative are identical (classes I-V, XIV, XVII, and XVIII). But given the close correspondence, discussed below, between those points in the system where explicit information IS available for all three systems, the possibility exists that the underrepresented classes were simply missed in the description.

5.4. Singular Suffixation.

The weak complementarity between stem alternation and suffixation in the singular holds in both Frank's and Vandevort's material (Table 24), with overt case suffixation (for one or both cases) preferred where the stem is invariant (72% in Frank's material, 70% in Vandevort's), and zero suffixation preferred where there is a stem alternation for case (66% in Frank's material, 61% in Vandevort's). Stem alternation has no observable effect in Crazzolara's material, where zero suffixation occurs more often across the board. [End Page 486]

Singular suffixation correlated with stem alternation, showing number of lexemes.

5.5. Plural Suffixation.

Recall that in Frank's corpus, plural suffixation patterns are sensitive to stem alternations. Where the stem alternates for number, all three varieties show the same pattern: an overt suffix (-ni or -nä) is preferred in the genitive/locative plural (an average of 89% in Frank's material, 92% in Vandevort's, and 88% in Crazzolara's), and zero is preferred in the nominative, to a somewhat lesser degree (Table 25). Note that the numbers for Crazzolara's material are based on segmental alternations only; tone has been omitted for two reasons: (i) to facilitate comparison with the other sources, and (ii) it is not clear whether tonal alternations that accompany suffixation are morphologically encoded, or the result of tone sandhi with the suffixes.

Plural suffixation where the stem alternates for number (tone omitted in Crazzolara's data).

Where there is no stem alternation for number, overt suffixation in the plural is preferred. In the genitive/locative plural, this is as good as a categorical rule in all three varieties. In the nominative plural it seems likewise to be a categorical rule in Frank's material, but in Vandevort's and Crazzolara's it is merely a tendency (72% and 60% respectively). With Crazzolara's material the results differ sharply depending on whether tone is considered. Table 26 gives the results with tone omitted, showing a weak complementarity between stem alternation and suffixation in the nominative. When tonal information is included, however, there is only one noun in the corpus that lacks both a stem alternation and an overt suffix in the nominative plural. One possible interpretation is that the same near-categorical rule is observable both in Frank's material and in Crazzolara's, and that tone really is nonphonemic in the variety described by Frank, or at least plays no role with respect to this rule.

Plural suffixation where the stem does not alternate for number (tone omitted in Crazzolara's data).

The final generalization about plural suffixation is that -ni suffixation in the nominative plural implies -ni suffixation throughout the plural. This holds across all three varieties: it is practically exceptionless in Frank's material, and completely exceptionless in Crazzolara's and Vandevort's. [End Page 487]

5.6. Etymological Correspondences.

The preceding section confirms the basic similarity of the inflectional rules governing all three varieties, in spite of a number of differences. We can now take advantage of the existence of these other varieties to clarify the status of the morphological indices. That is, even if the inflectional rules display diachronic continuity across the different varieties, the lexical indices might still be some kind of ephemeral property, assigned on the fly. Alternatively, like the inflection classes of Indo-European languages, they may be diachronically stable lexical features, in which case cognate items might be expected to display the same inflectional behavior. This turns out largely to be the case for Nuer. Figures 4-6 below compare the singular and plural paradigms of cognate nouns between the three varieties. Note that because appropriate conditions for comparison between two cognate nouns are not always met in both numbers, 13 the figures for singular and plural do not quite match.

[End Page 488]

The majority of cognate items display matching suffix paradigms: out of a possible 449 pairwise comparisons (the singular and plural paradigms compared between each pair of varieties), 391 match, or 87%. The fifty-eight nonmatching pairs in turn largely follow a single trend, namely an increasing tendency to use overt suffixes in the varieties described by Frank > Vandevort > Crazzolara. (Forty-five of the discrepancies, or 78%, can be so characterized.)

5.7. Western Nilotic Perspectives on the Case-number Suffixes.

It is not clear exactly how the Nuer case-number suffixes came about, but there are intriguing hints from related languages that they may be of composite origin, involving linker suffixes and plural suffixes. Linkers (suffixes or free-standing words) of the form kV and nV, used to link two nouns in (at least some types of) adnominal constructions, are found in most of the other Western Nilotic languages (Storch 2005:386). At first glance these look like the Nuer genitive/locative suffixes, but there are two important differences. First, in the other languages the linker follows the head, while in Nuer it follows the dependent; compare Mayak (6a) and Nuer (6b).

6.

a. gŠŠc

pII

calabash LINKER water

'calabash for drinking' (lit. 'calabash of water')

b. cuk pii -ni jar water-GEN.PL 14

'water jar' (lit. 'jar of water')

Second, in the other Western Nilotic languages, the number values of the linkers are not what is found in Nuer. Either kV is used in the plural and nV in the singular, the opposite of what is typically found in Nuer (though recall the exception noted in §5.2), or they are insensitive to number. For example, in Labwor they are distributed according to type of modification, with ká used for inalienable possession and nà as a general linker (Storch 2005:378f.); note that alienable possession involves the juxtaposition of two nouns with no linker at all. Thus if the Nuer genitive/locative suffixes are indeed related to the linkers found elsewhere in West Nilotic, it remains to be explained how they acquired their position in the construction, as well as their particular number values. On the assumption that there is a relationship, the fact that, elsewhere in West Nilotic, some adnominal constructions involve a linker and some do not may be a step toward a diachronic [End Page 489] explanation of why some Nuer nouns have overt suffixes and some do not. (Of course, all of this accounts only for suffixation in the genitive; how the locative will have acquired these suffixes is unclear.)

Another possible source of the Nuer suffixes is the common Western Nilotic plural suffix -nV, found in most of the languages (Storch 2005:385). In these other languages it is clearly distinct from the linker nV. If both of these are related to the Nuer plural -ni, that would mean that nominative plural -ni and genitive/locative plural -ni had different diachronic sources, with plural -ni and (originally singular?) linker -ni conflated into a single multifunctional plural suffix. This might account for the differences in their distribution.

6. Conclusion.

The striking feature of Nuer case-number suffixes is their combination of formal simplicity—three overt suffixes plus zero—with extreme distributional complexity. On the one hand this is manifested by a wealth of inflection classes that are so poorly differentiated from each other that it looks, on the face of it, that the bulk of the forms must be memorized. On the other hand it is manifested by an erratic mapping between form and function: the suffixes cannot be tied to a single invariant meaning, though they do cluster around functionally coherent chunks of the paradigm (oblique singular for -kä and -ä, plural for -ni). On a view of morphology that divides phenomena into regular and irregular, this system is neither; rather, it maintains a delicate balance between order and chaos. The aim of this article has been to construct a model of inflection precise enough to capture the observable patterns, yet loose enough to allow for the apparent indeterminacy so characteristic of the Nuer paradigms.

The key to understanding the complexity of the inflection class system, I have argued, is to view it as bound to the system of stem alternations. In contrast to the suffixes, these stem alternations display not just complexity of patterning, but also complexity of exponence, in terms of (i) the sheer number of operations (involving vowel length, phonation type, and assorted other vocalic and consonantal alternations), multiplied by their combinability, and (ii) their noniconicity, in that these operations characterize simply a contrast of meaning, without being linked to any particular meaning. It is these properties that Nuer shares with other Western Nilotic languages, which will be familiar to many from the literature, such as Dholuo (Gregersen 1972; often cited as an example of 'exchange rules'), Shilluk (Gilley 1992), and Dinka (Ladd et al. 2009). These are systems in which the stem alternations must, to some large measure, be memorized. Thus Ladd, Remijsen, and Manyang (2009:668) conclude that, in Dinka, there is no observable semantic or phonological motivation to the choice of plural stem-forming operation; and even though there is a preferred pattern for derived and borrowed words, speakers are reluctant to speculate about novel items. On top of such a system Nuer adds an additional complication, namely complexity of patterning. Partly this is due to the larger size of the paradigm (the other languages have only singular ~ plural stem alternations), and partly to the fact that alongside various types of stem alternations, Nuer nouns may also NOT alternate (as opposed, say, to nouns in Dinka, which always do). Indeed, as Frank discovered (1999:21-23), complete absence of stem alternation is the default pattern, as revealed by wug-tests, even though it covers a minority of lexemes in his corpus. Thus the stem paradigm of a Nuer noun requires knowledge not just of the type of alternation involved, but also of whether an alternation occurs at all. If we take this knowledge as a given (be it stored or be it generated through some as yet undiscovered rule system), much of the apparent chaos of the suffix system is resolved: it is an echo of the complexity of the stem alternation patterns. [End Page 490]

The erratic form-function mapping of the suffixes—for example, the fact that -kä is either genitive or locative, or both—is a typologically unusual phenomenon that has not been addressed by morphological theory. This indicates a separation between morphological forms and the morphosyntactic values they realize, but crucially, the separation in this instance is highly restricted: -kä and -ä are oblique singular suffixes and -ni is a plural suffix, though these functional labels characterize their maximal distribution, and not necessarily their actual distribution in the paradigm of any particular lexeme. In the approach advanced here, inflectional exponence has been split into two parts: (i) the association of morphosyntactic values with a morphological index, and (ii) inflectional rules that license or prevent the morphological realization of this index within particular cells of the paradigm. The second part of this model ensures (in this instance) that each suffix is restricted to a coherent portion of the paradigm, while the first part allows individual lexemes or classes of lexemes to make idiosyncratic choices within that.

The resulting model combines insights gained from work on principal parts, defaults, and implicational rules, notions that feature prominently in much contemporary work on morphology (e.g. Finkel & Stump 2009 on principal parts, Brown & Hippisley 2012 on defaults, and Ackerman et al. 2009 on implicational rules). An important feature of this model is that morphological indices play the role of principal parts in the lexical entry, and so provide a measure of the lexeme's degree of exceptionality. They also enable lexical entries to be constrained, since morphological indices that deviate from the paradigmatic constraints are simply ignored. The incorporation of default inflectional patterns in turn leaves the indices with relatively little work to do, since they need only identify deviations from the default (in contrast to some other recent work on principal parts, such as Finkel & Stump 2009, in which defaults are not assumed). And implicational rules play a role both between suffixes—for example, the fact that -ni in the nominative plural implies -ni in the entire plural—and more importantly, between stems and suffixes. Here the implicational rules fall into two types: absolute (lack of a stem alternation in the plural forces -ni suffixation) and default (e.g. where there is a stem alternation in the plural, -ni is suffixed by default, but this can be overridden). This expresses the difference between deterministic rules and those subject to conditions

The ultimate aim of this study has been to show that the Nuer case-number suffix system can be portrayed as the product of a system of rules, in spite of its complex patterning. Such a rule system crucially involves the recognition of distinctly morphological objects (the morphological indices) and benefits greatly from the admission of implicational rules that allow the system of stem alternations to do much of the work. Whatever novel juxtapositions of elements this model may contain, it is ultimately a conservative approach, as it sees the stem as the repository of lexical exceptionality, and the affixes as the product of a system with broad application over the whole lexicon. This is implicitly opposed to a holistic approach in which whole word forms are stored in the lexical entry, with any additional forms supplied by analogy, for example, the usage-based approach of Bybee (2001) or ANALOGICAL MODELING (Skousen et al. 2002). On the face of it, these approaches differ from the one offered here in that they do not build in morphological segmentation, and their rules are not deterministic. However, I believe any differences are more a matter of emphasis than of conception. First, even a whole-word approach must, in order to model analogy, recognize distinct phonological positions or constituents in the word form, to which different generalizations will apply. Whether or not we commit ourselves to a distinction between stem and suffix, there are distributional properties that distinguish the word-final elements from what precedes them: (i) their scope over the lexicon is much greater; for example, in Frank's corpus, [End Page 491] 95% of the nouns have a plural form ending in -ni, while no stem alternation process accounts for more than 23% of the plurals (1999:2), and (ii) the paradigm-internal distribution of the suffixes is more constrained (compare the twenty-five suffix patterns with the forty-eight stem alternation patterns). The second possible point of difference is in the deterministic versus probabilistic nature of the rules. As suggested above, the model outlined here in fact accounts for both kinds: the absolute rules are deterministic, while the default rules are inherently probabilistic, in that they can be overridden.

Guildford, Surrey GU2 7XH

United Kingdom

m.baerman@surrey.ac.uk

revision invited 28 October 2010;

revision received 30 March 2011;

accepted 13 February 2012]

Appendix: Formal Implementation of the Inflectional Rules

Below is a DATR implementation of the rules laid out in examples 1-5 in the article. The 'mor' prefix identifies a morphological form, 'stem' identifies stem alternations, and 'index' is the morphological index.

NOUN:

<mor sg nom> == SINGULAR:</ZERO/>

<mor sg> == STEM_SG_GEN:<"<stem sg gen>">

<mor pl nom> == STEM_PL_NOM:<"<stem pl nom>">

<mor pl> == SUFFIX_PL_NOM:<"<index pl nom>">

<stem> == inert

<index> == undefined.

SINGULAR:

<> == ka

</ZERO/> == 0

</A/> == a

<undefined loc> == SINGULAR:<"<index sg gen>">

<undefined gen> == SINGULAR:<"<index sg loc>">.

ZERO_SINGULAR:

<> == SINGULAR

<undefined> == SINGULAR:</ZERO/>

<undefined gen> == ZERO_SINGULAR:<"<index sg loc>">

<undefined loc> == ZERO_SINGULAR:<"<index sg gen>">.

STEM_SG_GEN:

<inert> == STEM_SG_LOC:<"<stem sg loc>">

<alternating> == ZERO_SINGULAR:<"<index sg>">.

STEM_SG_LOC:

<inert> == SINGULAR:<"<index sg>">

<alternating> == ZERO_SINGULAR:<"<index sg>">.

STEM_PL_NOM:

<inert> == PLURAL

<alternating> == PLURAL_NOM:<"<index pl nom>">.

PLURAL:

<> == ni

</ZERO/> == SINGULAR

<undefined gen> == PLURAL:<"<index pl loc>">

<undefined loc> == PLURAL:<"<index pl gen>">.

PLURAL_NOM:

<> == SINGULAR:</ZERO/>

</NI/> == PLURAL.

SUFFIX_PL_NOM:

<undefined> == OBL_PL_STEM:<"<stem pl nom>">

<> == PLURAL.

OBL_PL_STEM:

<inert> == PLURAL

<alternating> == OBL_PL_STEM2:<"<stem pl gen>">. [End Page 492]

OBL_PL_STEM2:

<inert> == PLURAL

<alternating> == SUFFIX_PL_NOM2:<"<stem pl loc>">.

SUFFIX_PL_NOM2:

<inert> == PLURAL

<alternating> == PLURAL:<"<index pl>">.

References

Footnotes

* I would like to thank those who have offered invaluable commentary on earlier versions of this article: Dunstan Brown, Patricia Cabredo-Hofherr, Marina Chumakina, Scott Collier, Greville Corbett, Enrique Palancar, Bert Remijsen, and Anna Thornton. I am particularly grateful to the five anonymous referees, and to Language associate editor Harald Baayen, whose many careful criticisms and suggestions have improved this work immensely. The work here was funded by the European Research Council (grant ERC-2008-AdG-230268 MORPHOLOGY), whose support is gratefully acknowledged.

1. The practical orthography employed in Frank's (1999) study corresponds to the International Phonetic Alphabet except for the following: (i) th, dh, nh are described as stops with something between interdental and dental articulation, and (ii) the following IPA correspondences obtain.

| CONSONANTS | VOWELS | |

|---|---|---|

| j = IPAɟ |

|

|

| ny = IPAɲ |

|

|

| y = IPA j |

ë = |

|

| Ɣ = IPAɦ |

|

|

Thus vowel diacritics always indicate breathy voice, among other things. The vowel /u/ has no phonation type contrast (it is always breathy voice), and the same is true for /i/ when it is word-final. In both cases no diacritic is used in the present article.

2. There are a few singularia and pluralia tantum nouns, and also some that are given only in the nominative or only the nominative and genitive. The classification in Table 7 is not Frank's. He treats stem alternations and suffixation together, yielding 208 different types. The scheme here was arrived at by separating out the suffix patterns from the stem patterns. The principles of arrangement are: aberrant paradigms (XXIV, XXV) are placed at the end, and next to them, paradigms that have the rare genitive/locative singular suffix -ä (XVII-XXIII). Otherwise, the arrangement goes from largest to smallest classes.

3. Available at http://www.cs.uky.edu/~raphael/linguistics/analyze.html. Note that the figures given by Malouf and Ackerman (2010) for Nuer are based on a smaller set of inflection classes than the one considered here.

4. The opposition of grade 2 vowels to grade 1 largely involves raising and, in the case of some modal voice vowels, the addition of breathy voice phonation. Note that the two grades may overlap; for example, /ε/ can be a grade 1 vowel or the grade 2 alternant of /i/ and /a/. Whether this system can be applied to Frank's material is unclear; Storch's material differs from his in a number of details, and I have not been able to detect any regular correspondence between the grade alternation system she describes and the patterns found in Frank's corpus.

5. The fact that this falls short of the logical maximum is probably accidental. Three lexemes in Frank's corpus have five stems, but according to two different patterns: two have identical genitive and locative plural stems (jiök 'dog' and buäw 'kind of tree'), and one has a single stem for the nominative singular and genitive plural (gök 'bag'). There is no plausible principle that would allow both of these patterns but prohibit a lexeme with six stems.

6. This is the equivalent of an adaptive principal parts system (Finkel & Stump 2007): the nominative singular is the basic principal part, which can then be supplemented with the genitive singular or nominative plural.

7. Only two indices will have any effect in the singular, since the nominative is invariably ZERO, so any lexical specification here is ignored. In the plural likewise at most two can have an effect. The nominative may be lexically specified as NI, with its form being otherwise assigned by the inflectional rules, while the genitive and locative may each be specified as NI or ZERO. In theory, this would allow for three lexically specified morphological indices in the plural, but because of rule 4a, lexical specification in the nominative precludes lexical specification in the genitive and locative. Thus the plural can be lexically specified for the nominative, or for the genitive and locative, but not all three.

8. It may be worth noting that the classes involving the genitive/locative singular allomorph -ä are, on the whole, smaller than their average number of morphological indices would predict (classes XVII-XXIII). In order to incorporate this into the formalism we would have to make the lexical specification of -ä costlier, perhaps by weighting the morphological indices. But this would involve an additional complication to the overall system, whose goal has been to show how to balance a defaults-based set of inflectional rules with an optimized lexicon. For the present, I assume this is a separate layer of structure whose consequences remain to be researched.

9. The figures below for Vandevort's and Crazzolara's material vary somewhat, due to the fact that for some nouns they give alternative forms; where relevant, each alternative has been counted as a separate item.

10.

An additional phenomenon affecting -ni, not alluded to in any of these descriptions, is the ATR harmony reported by Storch (2005:209), for example, 'baboons' vs. bìéyní 'clothes'. ATR harmony affecting both plural and singular suffixes may also be behind the allomorphy in Stigand's (1923) dictionary entries, where the genitive/locative singular is variously given as -ka and -ke, and the plural as -ni and -ne. As a purely phonological phenomenon, its presence or absence will not affect the description of the inflectional rules.

11.

Note that with titi

'these', and probably also with 'those' (the subscript dots indicate extra short vowels), -kä is found in the plural in Vandevort's material. It may be of significance that demonstratives are suppletive for number; that is, they may in some sense be morphological singulars pressed into service for a plural function. In any case, Frank does not discuss demonstratives and Crazzolara cites only the nominative, so it is not clear whether this is a shared property.

12. Less certain examples are roŠƔ 'kidney', which appears to behave like nath, and puŠƔ 'bath' or tεac 'larva of gadfly', which appear to behave like tŠŋpiny.

13. There are two conditions that have led to the rejection of a cognate pair. The first is where the paradigms in Frank's material display different suffixes in the genitive and locative, which makes it hard to know which one to take (this affects fifteen singular paradigms and eight plural paradigms; comparison with the other varieties does not reveal any clear pattern). Second, Vandevort's and Crazzolara's material contains some doublet forms, one with an overt suffix and one without, making comparison uninformative (from Vandevort's material this affects ten nouns in the singular and one in the plural; from Crazzolara's, four nouns in the plural). In addition, there are some nouns in Vandevort's material for which only the singular or plural paradigm is given.

14. 'Water' is plurale tantum.