The Long-Haired Gang Murder Trial: Mexican American Gender Deviance and the WWII Youth Gang Panic in the Houston Chronicle

Photograph of Isabel Garza, a Houston Pachuca, c. 1940s. Carmen Cortes Papers, Houston History Research Center, Houston Public Library.

[End Page 362]

Numerous histories of the home front during World War II have extensively documented the nationwide panic that exploded around zoot-suiters and Mexican American pachucos. The Sleepy Lagoon murder trial and Los Angeles Zoot Suit Riots of 1943 are particularly well-trod episodes in Chicano history, skewing perceptions of this history as a predominantly Californian phenomenon.1 Consequently, the history of wartime persecutions of ethnic Mexican youths in Houston, Texas, has received considerably less consideration by Chicano historians.2 This essay addresses that shortfall. It not only illuminates an underexamined local history of the nationwide Mexican American youth gang panic, but identifies several important ways in which Houston’s racialized wartime crackdown on juvenile delinquency differed from contemporary episodes that occurred elsewhere in the United States.

Responding to Eduardo Obregón Pagán’s call to move away from flattened narratives of Mexican American victimization, this essay presents a challenging narrative of intracommunity and intergenerational conflict: the criminalization of Mexican American youths by Hispanic adults. Unlike Los Angeles, where the [End Page 363] Foreign Relations Bureau of the Police Department was overseen by an Anglo officer named Edward D. Ayres, the Houston police department (HPD) hired its first Hispanic officer, Manuel Crespo, in June 1942 to lead investigations into local “Latin-American” cases.3 Despite Crespo’s prominent leadership roles in Mexican American civic organizations, greater Hispanic involvement in the HPD actually led to the intensification of racially motivated policing of Mexican American youths. By describing the collaborative efforts of law officers, Houston Chronicle reporters, and Hispanic leaders to depict a youth movement in Houston as a gang crisis, this essay revises previous historians’ interpretations that blamed Mexican American youths in the city for an alleged rise in criminal behavior.

This paper also seeks to shift the sartorial focus of previous studies of pachuquismo. Houstonians associated Mexican American juvenile delinquency not with the often maligned figure of the zoot-suiter but, overwhelmingly, with “long-haired” youth. The focal point of the wartime pachuco panic in Houston was the 1943 murder trial of a group of ethnic Mexican youths known to the HPD as the “Long-Haired Gang.” And rather than tearing off zoot suits, Houston youths recalled how police harassment of young Mexican Americans usually involved officers grabbing boys off the street and forcibly “clipping” their long hair. Those who resisted “were beaten severely by police.”4 Through its focus on local press coverage of the Mexican American “longhairs,” this essay follows Catherine Ramirez and Elizabeth Escadebo’s calls to recover the histories of femininity and gender deviance in the history of pachuquismo.5 The trial of the Long-Haired Gang not only hinged on the eyewitness testimony of two young Mexican American girls and targeted at least one female member of the supposed youth gang, but also invariably raised the specter of wartime criminalization of Mexican American girls’ sexuality.

Historian Arnoldo De León has claimed that the “sensational discussion” of the Long-Haired Gang’s alleged murder of Jose L. “Joe” Pacheco in March 1943 marked the start of the local panic regarding youth gang violence. Careful examination of Houston newspaper coverage, however, reveals that the hysteria began at least six months earlier, shortly after a September 16, 1942, celebration held in Houston’s city auditorium.6 Frank Hernandez, a sixteen-year-old “hall boy” at the Texas State Hotel, surrendered to police after he allegedly shot and killed eighteen-year-old Roy Mares. As Hernandez explained to police, the incident followed trouble with a group of Fifth Ward boys known as the “Blackshirts.” He claimed that he was threatened by them after he testified in court against a member of the group who had stabbed him in the stomach and [End Page 364] robbed him several months earlier. Hernandez borrowed a pistol from one of his friends to protect himself before taking a seat in the balcony to watch the evening’s stage show. When the house lights began flickering during intermission, he claimed that he saw the same group of “Fifth Ward boys” approaching him in the balcony. He told the officer: “I took the gun out of my blue coat. I saw that they had knives. I shot one time in the dark.” In the chaos following the gunshot, Hernandez fled the theater for Sam Houston Park, where he threw the gun into the bushes, but on his way home to Houston’s Sixth Ward, he encountered friends who advised Hernandez to surrender to police. When he followed their advice, he was arrested and his case was transferred to the county probation department, where he was tried in juvenile court.7

The following week, Houston Police Chief Percy Heard instructed “all departments of the police force . . . to exercise the utmost vigilance” in investigating what the Houston Chronicle called “gangs of youthful lawbreakers of Mexican parentage.” He alleged that the youths were “demanding tribute from boys in regular jobs” and committing other misdemeanor crimes, such as disturbing the peace and assault. Although Chief Heard partially blamed the city for its lack of recreational facilities for Mexican youths, he hinted that the older Mexican community members might also be at fault, claiming that the gangs were led by “boys beyond the juvenile age.”8 Soon afterward, District Court Judge Frank Williford gave $9,287.68 to the grand jury in November 1942 to investigate juvenile vice, specifically instructing them to look into three gangs who he alleged had organized with intent to “rob, burglarize, maim, and murder.” These the HPD would identify elsewhere as the “Black Shirts,” “Snakes,” and “Long-Haired” gangs.9 Judge Williford alleged that these youth groups congregated in “honky-tonks” that he derided as “glorified houses of prostitution” and “breeding places of crime and evils.” He promised to give the grand jury additional public funds to support the investigation later that month. He also told the eleven White men and one Black man who comprised the jury to “raise [their] voices and arouse public opinion to a point where it will create action in the legislative halls at Austin.”10

Thus began months of heightened scrutiny and heavy policing of Mexican youths across Houston. The local press began reporting widely on Mexican boys sent to Gatesville on charges of gang membership. They were accused of knife fights, holdups of smaller boys, and “running the streets at 4:30 a.m. with a small pistol, looking like a toy cap [gun].”11 By the start of 1943, Lt. A.C. Thornton of the HPD claimed that members of these gangs were responsible for “at least five killings and a number of assault to murder cases.” Chronicle reporters reprinted [End Page 365] police claims uncritically, including comparisons between the Houston youth gangs and the organized criminals of New York and Chicago during the 1920s, publicly equating the Mexican American youths’ various petty offenses to citywide organized crime. Although police noted that the members of these alleged gangs ranged from thirteen to twenty-two years of age, from the start of the investigation notions of childhood innocence were strategically deployed against these ethnic Mexican youths. The Chronicle highlighted that “one of the more objectionable practices of the gangs” was allegedly harassing “small children” walking to school and taking their lunch money.12

Such a pro-police stance was characteristic of the Chronicle’s coverage of Houston’s supposed “gang” problem under the ownership of Jesse H. Jones, who had maintained “acute and continuous” oversight of the paper’s editorial policies since he took full control of the newspaper in 1926. According to Jones, he bought Chronicle founder Marcellus E. Foster’s stake in the paper so that he could maintain full control over its politics, explaining in a signed editorial that under his stewardship the Chronicle would continue “championing and defending what it believes to be right, and condemning and opposing what it believes to be wrong.” Jones’s personal politics were “conservative” and pro-business, which led to his appointment to direct the Reconstruction Finance Corporation and a five-year term as Secretary of Commerce for Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt. His editorial policy was praised by Houston judges involved in the city’s campaign against Mexican youth gangs, including Roy Hofheinz and Roy Campbell. As the “most widely read newspaper in the state of Texas,” with “thousands of daily readers” by the start of the 1940s, the Houston Chronicle was an influential news source for city and state leaders, and it remained the primary mouthpiece through which the Houston police constructed their narrative of Mexican American youth criminality.13

With the full-throated support of the local press, led by the Houston Chronicle, the HPD’s juvenile delinquency campaign against Mexican youths escalated dramatically. On January 16, 1943, police raided thirty dance halls, beer joints, and “street corner hangouts,” and arrested more than twenty youths suspected to be members of the three “Mexican gangs.” The raid followed a week of surveillance by regular and auxiliary members of the HPD, who “cruised the streets of Mexican neighborhoods every night” to profile youths they claimed were visiting these supposed “hangouts of the gangs.” HPD officers interrogated the youths they detained that night about various misdemeanors that had recently occurred throughout the city. The Chronicle explained that the arrests of juveniles in Houston’s Mexican neighborhoods were “expected by Lt. A. C. Thornton to [End Page 366] clear up a number of these crimes, most of which were burglaries in which only small amounts were taken.” Thirteen of the older youths were transferred to the city jail while the rest, as juveniles under Texas law, were released to their parents after questioning.14

At a fiery meeting of the county juvenile board, Campbell, a state district judge, confronted W. E. Robertson, chief of the Harris County juvenile probation department, over the supposed “gang problem” in Houston. Robertson defended his department by pointing out that twenty-six Mexican boys had been sent to Gatesville in recent months. Several other judges present at the meeting also explained that about twenty older youths had been sent to the state penitentiary and suggested that many other Mexican youths under indictment would soon join them.15 That same day, HPD homicide officers alleged that members of the Long-Haired Gang were responsible for burglarizing the Kein Ice Cream store in Houston Heights, noting that one of the Mexican youths was “distinguished by their long hair.”16 A few days later, Thornton said that as many as eight or nine Mexican youth gangs were operating in the city, including the “Old San Antonio Gang” and “Fifth Ward Gang,” and alleged that the groups were “becoming bolder” in their attacks. He again attributed several unspecified murders to the gangs in his remarks to the Chronicle.17

The HPD triumphantly announced at the start of February 1943 that they had arrested one of the last members of the “Black Shirt Gang,” a fifteen-year-old boy “of Mexican heritage” at a local theater. Hofheinz, as a Harris County judge, sent him to Gatesville for stealing “80 cents in coin and 20 pennies from two smaller children.”18 Then, two weeks before the death of Pacheco, Houston’s Wartime Youth Council held a “patriotic rally” at the City Auditorium, where Maj. Gen. Richard Donovan spoke to more than 3,000 audience members, mostly high school seniors, on the causes and dangers of juvenile delinquency. Donovan linked the apparent rise of juvenile crime to conditions on the World War II home front, arguing that “none [were] more sensitive to its rigors than children.” He blamed the increased reports of juvenile crime on “homes disrupted by abnormal hours, by the absence of parents working in war industries, by the removal to strange communities . . . [and by the] weakening of the moral fiber of the country.”19 Educator and activist Luis Rey Cano later noted that the Houston Wartime Youth Council was “primarily geared toward” White youths, while Mexican American youths were “noticeably absent” from the organization.20 [End Page 367]

As this timeline demonstrates, the alleged crimes of the Long-Haired Gang were not the cause of the city’s Mexican juvenile delinquency panic. Instead, the accused youths became its most visible target. When Judge Williford tasked the May 1943 term of the Harris County grand jury to continue the citywide investigation of juvenile gangs, he touted the recent trials of alleged members of the Long-Haired Gang as an example of the “great strides in control” that were made as a result of the preceding grand jury. The judge called on jurors to extend city officials’ power over sites of commercial leisure with the explicit intent of pushing youths out into the streets and increasing their vulnerability to policing. “The sheriff and city police are policing them to death on the streets,” he explained to the all-white grand jury. “You can close those pool halls and turn them out on the streets to be policed.”21

Although boys were most often targeted by this campaign against youth gangs, Mexican American girls were not unaffected by wartime police harassment. In Los Angeles, English- and Spanish-language newspapers printed sensationalized reports on “girl gangs” with suggestive names like the Black Widows and the Cherry Gang. In the case of the Sleepy Lagoon murder case, Los Angeles newspapers found the alleged involvement of several young girls “particularly disturbing,” and many of the girls swept up in the investigations were held in custody as material witnesses or sentenced to a local juvenile correctional facility.22 Ethnic Mexican girls in Houston were similarly subject to arrest for their alleged participation in youth gang crime. For example, two teenage “Latin-American girls,” Lena Hernandez and Delia Gonzalez, received sixty-day jail sentences along with eighteen-year-old Frank Cantu for the “gang assault” of a White girl and her friend.23 One of the alleged members of the widely maligned Long-Haired Gang was a twenty-one--year-old Mexican American woman named Eva Garcia.

Mexican American girls were also subject to the broader, nationwide policing of so-called “victory girls,” or V-girls. For Mexican American girls, the wartime anxieties around V-girls were especially fraught because encounters with White servicemen raised the specter of miscegenation, which threatened the “white social order.” For many adult observers, pachuca sexuality was not seen as a case of misplaced adolescent patriotism but abnormal and potentially criminal excess.24 In his May 1943 speech to grand jury investigators, Judge Williford raised concerns about the criminal sexuality of Mexican American girls in Houston when he described the honky-tonks frequented by alleged youth gang members as “glorified houses of prostitution.”

County probation officers in Houston began to label girls’ wartime sexuality as a serious problem a few months before the passage of the May Act of [End Page 368] 1941 by Congress, which sought to curb the spread of venereal diseases among servicemen by prohibiting the solicitation of sex in restricted zones near military bases.25 Harris County Chief Probation Officer Robertson claimed that the number of girl runaways was rising “in direct ratio with the increase in brass buttons and uniform in the country.” He claimed that it was an inevitable “natural problem” that Houston had to face with the opening of Camp Hitchcock and expansion of Ellington Field, a flight training base. He explained, “Wherever there [are] great concentrations of men, such as our national defense program calls for, there is going to be a runaway girl problem.”26 While the number of boys’ juvenile delinquency cases fell in 1941, Robertson’s annual report reflected an “enormous increase” in runaway girls in Harris County—from 316 in 1940 to 560 in 1941. He once more blamed the increase on the “concentration of a comparatively large number of men in army training camps” that he claimed was “an apparent attraction to girls.”27

In February 1942, the issue of runaway girls’ unchecked sexuality arose at a hearing of the Texas Liquor Control Board over concerns about carhop uniforms at drive-ins and beer joints in the state. Board chairman William J. Townsend described these outfits, called “scanties,” as “an outrage and disgrace” because they left working girls “almost naked.” A delegation of city officials and clubwomen from Houston were present to raise concerns about the scourge of scanties in the state’s largest city. H. K. Montgomery, who worked for Robertson as a probation officer, claimed that beer joints often hired vulnerable runaway girls to be their “scantily clad” waitresses, and Board members peppered him with questions about potential links to Houston’s night clubs and sex industries. Montgomery compared girls in scanties to “places in Houston where there are strip tease dancers” and specifically mentioned “one place where there is a nude dancer” in his testimony. He distinguished scanty carhop uniforms from theatrical costumes and bathing suits by emphasizing the scanties’ commercial nature, intended neither for recreation nor “art.” He also hinted that the uniforms threatened to erase the distinction between the selling of “food and drink” and the selling of the girls themselves.28

Throughout the hearing, witnesses emphasized the vulnerability of working-class girls, offering paternalistic and materialistic arguments for banning beer joint and drive-in scanties. Houston Supervisor of Policewomen Ruth Beem called on the Board to protect vulnerable young girls by issuing regulations that would require drinking establishments to keep “more clothes on these girls than a brassiere—and some little panties.” She described the policy as a precaution [End Page 369] against juvenile delinquency and a public health measure, arguing that the policing of their work uniforms would improve both the moral and physical “health” of girls, as their exposed skin was threatened by “sun rays” and damp weather. Houston clubwoman Helen Stowe worried more directly about the human dangers faced by “country girls” in a “big city like Houston,” where runaway girls, seduced by the “glamorous” city life, were “easy prey to men who loiter about” beer joints and drive-ins.29 Policing runaway girls was not merely talk for Houston officials, as Robertson’s Probation Department and the HPD Crime Prevention Bureau worked together to develop a wartime surveillance network in collaboration with the proprietors of drive-ins, cafés and “other businesses where girls usually appl[ied] for work” in the city. Employers reported runaway girls so that police could detain and question juveniles suspected of being in the city without parents or legal guardians.30

As the war continued and venereal disease continued to rise among servicemen, runaway girls’ sexuality began to be more explicitly criminalized by authorities and portrayed as deviant and dangerous. At the meeting of the Houston Venereal Disease Control Committee, probation officer Robertson testified that “most” runaway girls found employment not as carhops or waitresses, as he had previously claimed, but as prostitutes. He also said that of forty runaway girls recently investigated by his department, eleven “had venereal disease.” As a part of the campaign against venereal disease, Harris County Sheriff Neal Polk offered his plan to target women and girls “around beer joints and drive-in stands,” whom he suspected “to be the main source of venereal disease here among soldiers and the general public.”31 In 1943, Beem headed the official launch of the HPD’s drive against “Victory Girls” in Houston, bringing together resources and officers from the city’s morals division, the military, and the Crime Prevention Bureau to increase the surveillance of girls in the city.32

By 1943, the Chronicle was reporting that “teen-age girls” were “prowling the streets at night” alongside delinquent boys, with the head of the city’s Crime Prevention Bureau blaming the rise of juvenile crime on both the employment of mothers in war plants and the concentration of “men in uniform” in the city.33 To manage the threat of girls’ unchaperoned sexuality, three Houston policewomen were tasked with patrolling the U.S.O., military depots, and bus terminals. According to Beem, they detained about one dozen girls each night who were sent to parents or authorities. Beem justified the program with the claim that sixty-five percent of servicemen’s venereal diseases were the fault of “girls under 21,” and thirty-five percent could be attributed to girls under eighteen. [End Page 370] She explained that all girls who were picked up by officers were required to follow up with policewomen with a doctor’s certificate proving that they had been treated for venereal disease. Beem echoed the popular argument that the unchecked sexuality of “Victory Girls” was the fault of the lapsed chaperonage of parents “occupied with war work.”34

By 1945, the campaign to police girls’ sexuality in Houston began to receive sharp criticism from local military officials for not going far enough to criminalize and incarcerate unchaperoned girls and young women. Col. E. V. Harbeck Jr., commanding officer of Ellington Field, expressed his hostility toward V-Girls and the county courts at a July meeting of the Houston Venereal Disease Control Committee, claiming that county judges were too “lenient” with girls charged with prostitution. He got support from the head of the police morals division, Capt. J. R. Davidson, who lamented that girls accused of prostitution had “all the advantages of the technicalities of the law” to help them evade prosecution when arrested on vagrancy charges. Texas Business Court Judge Cleo Miller and Houston Municipal Court Judge Walter Chalmers responded to these accusations by pointing out that prostitution cases were being presented in their courtrooms with “practically no evidence at all” to support a legal conviction. Pinning the blame for wartime venereal disease wholly on “victory girls,” whom he disparagingly called “patriotutes,” Davidson doubled down on his argument that the most effective public health solution was incarcerating girls: “[K]eep picking them all up, detain them in the detention ward and keep them out of circulation as long as possible,” he advised.35

Doubly targeted by two sensationalized juvenile policing campaigns, Mexican American girls found their lives heavily circumscribed during World War II. Revisiting this intensified policing of youths and in particular Mexican American girls in this wartime panic over juvenile delinquency provides more useful context on Houston’s prosecution of the supposed “Long-Haired Gang.” Examining the investigation and trials surrounding Pacheco’s March 1943 murder reveals not only the experiences of one alleged female member of the Gang, Eva Garcia, as well as two other Mexican American girls that were key witnesses for the prosecution, but also the Mexican American boys’ experiences with pathologization and criminalization because of their supposed feminine excess as “long-haired” youths. Tensions arose not only between the city’s White leaders and Mexican American youths targeted in the campaign against “gang warfare,” but within the ethnic Mexican community along lines defined by age and gender as Hispanic adults sought to “get the youths to abandon their extra long haircuts” to distance the hairstyle’s criminal stigma from Houston’s Mexican community.36

As noted above, the Long-Haired Gang case began following six months of intensified policing of Mexican American youth. Police investigations began [End Page 371] when Arnold Gallegos, a thirteen-year-old boy, discovered Pacheco’s body with “his left arm and shoulder amputated and his head bashed” beside the Southern Pacific Railway tracks near Navigation and 72nd Street in Houston’s ethnic Mexican neighborhood of Magnolia Park. Pacheco was a resident of Magnolia Park and lived just a few blocks from the tracks at 7319 Avenue J. The initial coroner’s report determined the cause of Pacheco’s death as “injuries received in train.”37 Pacheco’s funeral was managed by the Crespo Funeral Home, and he was interred on March 16, 1943, in Houston’s Hollywood Cemetery.38

In a railroad city like Houston, train-related accidental deaths and injuries similar to Pacheco’s were a common, albeit unfortunate, occurrence.39 But Lieutenant Thornton, head of the HPD homicide squad, declared that he was “unsatisfied with the evidence” related to Pacheco’s death. He began a homicide investigation with orders to “keep on the case until more evidence is obtained.” He assigned two detectives to the case: Hugh Graham and Manuel Crespo.40 Crespo, a Spanish-American resident of Magnolia Park, was the owner of the Crespo Funeral Home and a well-respected civic leader in the city’s Mexican community. By 1943, he had held leadership positions in some of the most prominent Hispanic organizations in Houston, including El Campo Laurel, Club México Bello, Club Internacional, and the Mexican Chamber of Commerce. He was also a founding member of LULAC Council No. 60, having joined when the chapter was chartered in Magnolia Park along with many other influential civic leaders. Crespo also helped to organize La Federación Regional de Sociedades Mexicanas y Latinoamericanas (FSMLA) in Houston, a coordinating committee composed of leaders of many Hispanic civic groups.41

FSMLA was heavily involved in the Mexican youth gang panic, as the organization called upon its members to submit recommendations to a Harris County grand jury on the issue of juvenile delinquency in July 1944. FSMLA organized a Juvenile Delinquency Committee to head a “strong effort . . . to get the youths to abandon their extra long haircuts, so that in the future the term ‘longhair’ will not have a place in the Latin American sections of Houston.”42 The Committee was a product of a meeting with Lt. L. D. Morrison of the HPD, who requested that it be formed in cooperation with the HPD to facilitate the construction [End Page 372] of playgrounds and parks to curb juvenile delinquency among Latin American youths. In a letter reporting on their meeting with Morrison, one FSMLA member claimed that Morrison blamed Mexican and Mexican American adults for juvenile crime because their leaders had failed to demand equal access to public recreational facilities as “taxpayers and citizens.” Morrison faulted FSMLA leaders for their overly moderate, deferential style of political activism, claiming that ethnic Mexican civic organizations approached civil rights issues not as rights but as “favors,” and so the group’s efforts stalled when they faced “any little difficult[ies].” Ironically, following this criticism, leaders of FSMLA acquiesced to Morrison and created the HPD-affiliated Juvenile Delinquency Committee.43

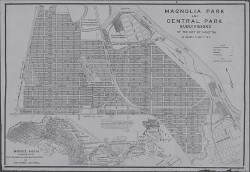

A bird’s-eye view sketch of Houston subdivisions including Magnolia Park, Central Park, and Ship Channel industries, certified by Sam’l E. Packard, a civil engineer for the City of Houston, in 1918. Magnolia Park and Central Park subdivisions of the city of Houston in Harris County, Tex., map on tracing paper, 1918. Public domain, courtesy University of Houston Libraries Special Collections.

Crespo became Houston’s first Hispanic police officer in June 1942. After spending several years assisting other police officers as an interpreter on homicide cases involving Spanish-speaking residents, the HPD hired Crespo as a homicide detective to investigate “Latin-American cases.” Crespo became a special detective without following the regular promotion track, meaning that he was authorized to enforce the law while lacking both experience and training. [End Page 373] Although Dwight Watson alleged in his study of race and Houston policing that “Latino officers had no community identity in Houston,” Crespo recalled that his status as a Hispanic officer allowed him a unique “acquaintance” with the Latin-American people in the city that led them to “tell [him] things they wouldn’t tell the other officers.” Crespo was one of three officers assigned to the Latin-American squad. As the only Hispanic member, he worked alongside D. H. Harrell and Lt. George Bell, a nine-year veteran of the HPD and a former Texas Ranger who was lauded as “an expert on handling Mexicans.”44

Decades later, when asked about the treatment of the “Latin-American community” in the 1940s, Crespo claimed that police discrimination against particular nationalities was limited to “some officers.’” Remembering his interactions with the “long hairs,” Crespo described his role in youth gang cases within the department’s Latin-American squad thusly:

When I got into these cases, they would tell me the same thing they would tell the other officers, “Well, the only one who can prosecute this is Crespo.” And the reason of course isn’t that I’m smarter than the other officers. It’s because I knew people and I had friends and they would give me the information I needed to prosecute and to tell me who the witnesses were, and then I was able to convince the witnesses of the necessity of prosecuting these cases because where are we going if we don’t? . . . I was able to convince them that it was needed to do this in order to stop it, not because I’m interested in prosecuting anybody. That wasn’t my job. My job was . . . to investigate the cases, get the information, and get the witnesses to testify. And that’s all I can. A lot of cases they told me I sent them to the penitentiary. I didn’t do that. The courts did that on the information by the witnesses.45

Crespo claimed that “no evidence whatsoever” remained at the site of Pacheco’s death when he began his investigation. Instead, he alleged that his lead on youth gang involvement came from rumors he gathered through conversations in Magnolia Park, explaining that one man told him that “two little girls”— Mexican American sisters named Esperanza and Aurora Rodriguez—had witnessed Pacheco’s slaying while “hidden behind some grass on the side of the tracks.” The sisters, despite their surnames, were not related to defendant Pete Rodriguez. In fact, they were Pacheco’s nieces and cousins of Thomas and Julio Guerrero, who lived about a block away from the train crossing where Pacheco’s body was found. Crespo went to the girls’ school and, with the assistance of the principal and the girls’ teachers, put them in separate classrooms for interviews.46 [End Page 374]

As Crespo recalled, the girls initially denied that they witnessed any alleged murder, so he “told [them] what happened” when Pacheco died, including “how it happened, where they were headed, what the rationale was.” When the girls’ continued to deny his claims, Pacheco had to “trick” the younger one into making an eyewitness statement:

So finally I thought it’d take a trick, and the trick was, I went to the oldest girl, went back to the youngest girl again. Said why was she refusing, your sister just told me. And you know what I’m telling you is the truth. I’m not asking you to tell me what happened. I know what happened. Isn’t it true? Oh yes, that’s true, that’s true. . . . Then we went to the house got the mother, the teachers, the principals to the police station and we took statements from all of them.47

According to the Chronicle, Detectives Crespo and Graham questioned a total of eleven people, obtaining several signed statements that provided conflicting testimony about Pacheco’s death. The initial signed statements from the two young girls alleged that Pacheco was killed with a lead pipe before being placed on the railroad tracks. His death was motivated by a threat he made to “expose” the Long-Haired Gang to police unless they left his seventeen-year-old son Henry alone. Others claimed that he was hit over the head with a bottle or that “some shots were fired,” although witnesses were not sure whether these supposed gunshots hit Pacheco.48

Presented with these new statements, Judge Ben Moorhead reopened the case and changed his verdict from accidental death to suspected murder. Murder charges were initially filed against six ethnic Mexican youths who all lived within a few blocks of Pacheco’s home in Magnolia Park: Thomas Guerrero, twenty-one; Julio Guerrero, eighteen; Pete Rodriguez, twenty-three; Adolfo Postel, fourteen; Eva Garcia, twenty-one; and Pablo Estrada, fifteen. Estrada was initially not identified in press coverage as the police had not yet taken him into custody. After the arrests of the other five alleged members of the Long-Haired Gang, who were held in jail without bond, Lt. Thornton issued a statement that the arrests had “broken the back of the gang,” because they had taken the leader, Thomas Guerrero, into custody. He was Pacheco’s nephew and had lost both his legs in a railroad accident several years earlier. Coverage of the trial often emphasized Guerrero’s disability, describing him as a “cripple” or “legless.” As his father later testified, “Tommy” navigated the neighborhood in a wheelchair and could not leave the duplex where he lived with his brother Julio and their parents without assistance to get down the steps of the front porch.49

The name of the Long-Haired Gang came from the youths’ adoption of the [End Page 375] “pachuco” style, a hairstyle anyone could wear irrespective of their capacity to afford a flashy zoot suit. “They all wear their hair long and slick and with the ends curled upward,” the Chronicle noted of the group. Such hairstyling ran counter to the accepted norms of young men’s grooming at the period, with popular men’s hairstylist magazines in 1942 encouraging readers to “Keep in Trim with Our Armed Forces,” as the so-called “military cut” hairstyle rose in popularity among pre-draft age boys who sought to signal their solidarity with soldiers. As Catherine Ramirez has argued in The Woman in the Zoot Suit, the pachuco style, with its exaggerated zoot suit attire and ducktail hairstyles, was seen by many as the “apotheosis of American masculinity” in its contrast to the clean-cut uniform of servicemen who represented the wartime masculine ideal. While boys and young men who adopted the pachuco style were derided as “unmanly and un-American” for their long, carefully styled hair and ostentatious suits, girls’ pachuca style also diverged from the gender ideals of the innocent, vulnerable “feminine patriot” and self-sacrificing working woman. Pachucas suffered racially charged condemnations of the supposed moral impurity of their “dark beauty,” in part because their self-styled “excess” reached freely across feminine and masculine gender boundaries. With heavy lipstick and mascara, high pompadours, broad-shouldered coats, letterman sweaters, draped slacks, short skirts, bobby socks, and huaraches all cited as mainstays of the Mexican American fashion trend, the pachuca’s style crossed the sartorial gender line.50

While the zoot suit was a popular symbol for wartime Mexican American youth, in Houston “long hair” was the most common visual marker of boys’ juvenile gang affiliation cited by both police and the local press. Houston police harassment toward youths who adopted a pachuco hairstyle was “very common” in the city, with Mexican American residents recalling that these youths “would be pulled into the police car and have their long hair clipped on the spot by police.” Those “who resisted this violation of their rights were beaten severely by police.” Detectives like Crespo and newspaper reporters regularly noted if boys involved in alleged criminal activity “wore their hair long,” and the months of sensationalized coverage of the trial of the Long Haired Gang helped to cement this image of Mexican youth criminality in the public’s mind.51 Even the leaders of FSMLA explicitly sought to dissociate the term “longhair” from their community.52 This local wartime fixation with the haircuts of alleged gang members serves as a stark reminder of how the boundaries of Mexican American youths’ gender norms were collectively enforced by parents, community leaders, and police power. This network of adult authority reacted against overly feminine fashions when they appeared on bodies outside of the legitimate boundaries of girlhood. Long-haired Mexican boys were specifically targeted and even criminalized [End Page 376] for their transgressive self-styling, and police resorted to extrajudicial violence to eliminate the “longhair” from city streets.

On March 26, Judge Moorhead called for Pacheco’s body to be disinterred to determine his exact cause of death. An autopsy was conducted that evening by Dr. R. F. Zepeda, a doctor at Jefferson Davis Hospital. The follow-up examination, which involved X-rays of the head, neck, chest, stomach, and pelvis, determined the cause of Pacheco’s death to be a “hemorrhage of the brain.” The same night, police detained another teenage boy, eighteen-year-old Paul Hernandez, for questioning. The next morning, the HPD claimed to have found a toy pistol that accounted for the gunshots a witness recalled in their initial statement, which investigators now alleged the Long-Haired Gang had used to scare Pacheco prior to their attack. After being under arrest for several days, on March 29, 1943, Hernandez was also charged with Pacheco’s murder.53

On April 2, 1943, Thomas Guerrero, Estrada, Postel, and Rodriguez were indicted on charges of murder “with a blunt instrument and by placing him on a railroad track.”54 The same day, Justice of the Peace W. C. Ragan sent the robbery case of another alleged member of the Long-Haired Gang, 18-year-old Martin Lopez, directly to a grand jury without an examining trial after police claimed that they recognized about ten alleged members of the Long-Haired Gang in the courtroom. Ragan claimed he acted to “prevent the intimidation of witnesses.”55 One week later, Tommy’s brother Julio was indicted for Pacheco’s murder. Julio was also indicted for a second alleged crime: assault to murder against twenty-two-year-old Nieves Cantu, who testified that Guerrero cut his head, neck, and arm with a pocket knife a few hours after Pacheco’s alleged murder. Garcia, the sole female member of the Long-Haired Gang charged with Pacheco’s death, testified that Cantu and another man started the fight by arguing with and hitting Guerrero before Cantu began “pawing” her. Garcia explained to the court that Guerrero was not the aggressor and was merely defending Garcia and himself from verbal and sexual assault.56 After nearly a month in custody, Garcia was finally no-billed by the grand jury on April 19 and murder charges were dropped. She was the only one of those initially arrested who was [End Page 377] not indicted, suggesting that perhaps her unique access to gendered innocence provided her a measure of legal protection.57

Whether her testimony regarding her experience with sexual assault played any role in the grand jury’s perception of Garcia as a perpetrator of violence is impossible to state with any measure of certainty. Nevertheless, her experience presents a sharp contrast to those of the two youngest members of the Long-Haired Gang. A week after their initial indictments, both Postel and Estrada were declared to be juveniles at a hearing before Judge Langston King. While initial reports claimed that Postel was seventeen years of age, testimony and evidence proved both boys were in fact under that age and were legally juveniles. Postel’s father Arthur presented his son’s baptismal record as evidence of his age, while Robertson used public school records to confirm Estrada’s age and birth date. Their cases were moved to the juvenile court docket. Both boys were returned to the juvenile detention ward at the old Jefferson Davis Hospital, and Estrada’s bond was set at $1,000, while no bond was asked for or set for Postel. Estrada was able to post bond and was released from juvenile detention within the week.58

Rodriguez and Tommy and Julio Guerrero had their bails set at $5,000 despite protests from their defense attorneys. The prohibitive cost of their bond is indicative of the tenor of the case against the supposed Mexican youth gang members, which was not supported by the quality of evidence presented against them. At a habeas corpus hearing for the three youths, the state called as witness Judge Moorhead, who oversaw Pacheco’s inquest. Moorhead offered tepid testimony explaining that Pacheco’s head injury may or may not have been caused by a blunt instrument like the pipe police claimed was used as a murder weapon. The defense called several more compelling witnesses, who challenged the narrative established by police investigators. Tommy and Julio Guerrero’s father testified that not only had Tommy remained at home all night from at least 4 p.m., the boy could not have even left the house without assistance, as he could not get his wheelchair off the porch without aid or navigate the neighborhood without someone else pushing him. He testified that Tommy was still on the front porch when they learned of Pacheco’s death at around 9:30 p.m. that night. The defense also called Pacheco’s teenaged son Henry to the stand, who testified that his father had “said he was tired of living” and drank heavily and often. Henry was asked whether his father’s threats to take his own life were related to Henry’s older brother Pete, who had recently gone AWOL while serving in the army. Henry also testified that his father had slapped him after finding him hanging out with the other boys of the neighborhood, including Tommy and Julio Guerrero, and made him go home when he caught Henry with the group. Another witness, a Magnolia Park resident named Toney Sanchez, testified for [End Page 378] the defense that while he was waiting for a bus around 9 p.m. he saw a drunk man standing by the tracks near where Pacheco’s body would later be found.59

The issue of language was heavily debated during this pretrial hearing. Throughout the testimony, defense attorneys repeatedly objected to the prosecution’s use of the word “gang” regarding the Mexican youths. Judge King overruled the objection, saying that because Pacheco referred to the boys as a gang, according to Henry’s testimony, the word would be used in the trial. HPD Lt. Graham Bell, assigned to investigate the Mexican youth gangs, downplayed the word’s criminalizing effect when he claimed that the word “gang” simply meant “a group of people.” Nevertheless, he still alleged that, in Houston, such gangs “parade the streets looking for trouble.”60

Tommy Guerrero’s trial began on April 26, 1943, with assistant district attorney A. C. Winborn indicating during jury selection that he would be asking for the death penalty for the youth.61 The Rodriguez sisters remained the prosecution’s star witnesses, with no mention made during the trial of Crespo’s coercion or coaching of the adolescent girls. A decade later, Estrada described the vital role that the Rodriguez girls’ testimony played in prosecuting the alleged members of the Long-Haired Gang.62 Esperanza testified under oath that she saw Tommy in his wheelchair on the ground floor of the movie theater that she and her sister attended that night and saw Julio and the others upstairs. Both girls claimed in their statements that, as they left the theater, they saw the group, led by Tommy, beat and rob a man before laying him on the train tracks.63 They claimed that they did not recognize the man as their uncle at the time, as it was dark and he was turned away from them, but that they recognized their cousins and the other youths present. Esperanza claimed that Tommy struck Pacheco in the head with a water pipe and, when the man fell, that he told Rodriguez to hit Pacheco again. When Rodriguez refused, she said that Tommy fired two shots with a pistol into the ground near the other boy’s feet and Rodriguez then struck the man again. Aurora testified that she ran away when the shots were fired, but Esperanza claimed that she stayed and saw the group place Pacheco on the tracks and only ran away when she heard the train coming.64

The defense argued that Pacheco’s death was simply an unfortunate accident, as had been initially reported by the county coroner. Arguing that the girls’ statements could not have been accurate, Tommy’s mother, Maria Guerrero, and a neighbor, Manuela Parrish, who lived in the same duplex with the Guerreros, testified that Tommy never left their home at 7503 Avenue K that evening. The trial only lasted two days, and the jury deliberated for about four hours before [End Page 379] returning with a guilty verdict. King sentenced Tommy to twenty years in the state penitentiary. When King subsequently overruled the defense’s motion for a new trial, J. A. Collier, Tommy’s defense attorney, gave notice that he would appeal the court’s decision. Collier initially claimed that he “found new evidence” that would provide an alibi for another of the boys, whom he said was “playing a guitar in an entertainment at the time.” But he amended his initial, incomplete motion, instead focusing on the fact that there were no Mexicans on the grand jury that indicted Tommy. The motion was eventually dropped, but the issue of the exclusion of ethnic Mexicans from grand juries in the county, and across Texas, would not be so easily dismissed a few years later when presented by Mexican-American civic leaders of LULAC in Hernandez v. Texas, when a murder conviction of a Mexican American in Texas by an all-White jury was overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court.65

Following Tommy Guerrero’s conviction, the trials for Julio Guerrero and Rodriguez were scheduled for the following month. About a week before their trials began, the arrest of another teenage Mexican boy hinted at the possibility that, in the face of racial bias in the local courts, Mexican American youths found extralegal ways to cope with their legal troubles. Police arrested eighteen-year-old Mike Aguilar for allegedly threatening Aurora and Esperanza’s father, Trifonio Rodriguez. The older man alleged that five boys followed him from a barber-shop to a nearby cafe, where one of the boys cursed at him when he refused to talk to him. He claimed that the boys told the cafe owner to throw Rodriguez out so they could “kill him,” threatening his life if he continued to allow his daughters to testify in the Long Hair Gang trials. The misdemeanor charge against Aguilar was dismissed, though, when he was drafted into the army a few weeks later. The girls’ testimony was not necessary for subsequent convictions because, after learning of the outcome of Tommy’s trial, both Julio and Rodriguez pled guilty to the charge of murder in Judge King’s court. They were sentenced to ten years in the state penitentiary. Before his brother and friend’s trial began, Tommy filed his motion to withdraw the appeal of his earlier conviction, and the three boys were soon transported to Huntsville.66

Esperanza testified once more during Estrada’s trial in juvenile court. As a juvenile, the harshest sentence that the fifteen-year-old boy could receive was incarceration until the age of twenty-one in the state reform school in Gainesville. But Estrada pled not guilty to the charges. He denied being present at the time of Pacheco’s death, and his defense presented witnesses who confirmed the boy’s alibi. Estrada credited his unique success at the trial to his fortunate access [End Page 380] to a “good attorney,” Bert H. Tunks, a future judge who was hired by a wealthy friend to defend the Mexican American boy, unlike his fellow defendants. After about an hour of deliberation, the jury found Estrada not guilty.67

That Estrada avoided the fate of the other alleged members of the Long-Haired Gang was remarkable since the police had a signed confession from the Mexican American youth. Estrada recalled that he was “terrified” into signing a confession to the crime, which he did not commit. He explained, “They told me they would throw me in a cell with a dead man like they had done with Tommy. I thought no one would come to help me.” He explained that the police subjected him to at least one cold-shower treatment to coerce him into a confession, a potentially lethal punishment and interrogation technique: “They never struck me. But once they put me in a nice cold shower, naked. And they kept telling me they’d put me in a cell with a dead man.” An internal investigation by the probation department in 1943 confirmed that shower punishments were practiced in the county juvenile detention ward for both boys and girls, although the staff at these facilities denied that the water was turned on. When asked how he was able to provide a detailed statement that corresponded with witness testimony, Estrada explained that the police provided the details: “The police told me over and over again the whole story. Every little thing they went over with me.” Former Homicide clerk R. E. Osborne, who took Estrada’s confession, supported his claims, telling the Chronicle: “I remember the case. I took everything he told me. Some of the details of the crime were shocking. Every once in a while he would stop and say, ‘I’m lying. I’m lying. I don’t know why I’m telling you all this.’”68

As Watson noted in his study, the HPD, including the “old Latin squad,” were notorious in the 1940s for “aggressive and brutal” policing in Mexican neighborhoods.69 John J. Herrera, a Mexican American attorney involved in the Hernandez v. Texas decision, reportedly claimed that “the pachuco could not get off the ground due to the fact that the young men of the barrio were beaten unmercifully by Houston police.”70 A decade later, additional evidence emerged that called into question the veracity of other witness statements in the Long-Haired Gang murder case. Frank Torres claimed that in 1943 when police detained him for questioning, they kept him from leaving until he signed a statement that “was covered with a white sheet of paper” to keep him from knowing what it said.71

Prize-winning Houston Chronicle investigative reporter Zarko Franks in 1952 brought to light the additional eyewitness testimony of Irene Infante, née Salinas, who told the reporter that, as a young girl, she had seen Pacheco shortly before [End Page 381] his death. On the night of March 13, 1943, when returning from a bakery with her aunt, she saw a man “staggering . . . like he was drunk” on the tracks at 72nd and Navigation while “the warning bells were ringing and the signal lights were flashing at the crossing” as a train approached. She explained that she knew Julio and Tommy Guerrero “by sight” and did not see them or anyone else near the drunk man that night. “My aunt and I walked across,” Infante recalled, “and the last time I looked the man was still walking on the tracks.” When asked why she had not told the jury what she had seen, she cited her youth and the failure of legal procedure: “I was only 11 then. I was told to come to court. I remember going once or twice. But I remember that I was never asked to say anything.”72

Franks confirmed with Tommy Guerrero’s attorney J. A. Collier that Collier did not know about Irene or her aunt, Josephine Trevino, at the time of the trial. Collier explained that he was aware of another witness, Lupe Garza, who refused to testify for fear of reprisal, but claimed that “Julio and the other boys were in his beer tavern” during the evening of Pacheco’s death. As Collier told Franks, he “could not afford to put [Garza] on the stand and vouch for his testimony because of the possibility of his backing up on what he told [me].” Although he did not testify on the stand, Crespo took a statement from Garza at the time of his investigation that similarly confirmed the boys’ alibi, contradicting the Rodriguez girls’ statements.73

Franks’ reappraisal of the Long-Haired Gang case came six months after Esperanza and Aurora Rodriguez attempted to recant their childhood testimony, filing affidavits with the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles advocating for the release of Tommy Guerrero. By this time, Julio Guerrero and Rodriguez had been free for two years, having secured early releases for good behavior.74 Tommy, described in the Chronicle as a “legless wheel-chair invalid” and “victim of tuberculosis,” remained in the hospital ward of the Wynne Unit at the state penitentiary.75 Esperanza echoed Garza’s fear of reprisal, although not from the Guerreros but from the HPD. She agreed to speak to Franks on the condition that her whereabouts would not be disclosed, as she claimed that she “feared Houston police.” She explained, “I will do anything to help Tommy except getting in police hands.” When asked why she and her sister Aurora had testified against Guerrero in 1943 and how their statements had matched so closely, Rodriguez claimed that they were both “told what to say.”76

Esperanza Rodriguez repeatedly emphasized the sisters’ vulnerability as Mexican girls in Houston. “We were both just little girls then,” she told the [End Page 382] Chronicle reporters. She claimed that the consequences of her false testimony had “been on [her] mind all these years . . . long before Pete [Rodriguez] got out of the pen,” but she did not have the means to make amends because of the continuing threat of violence and abusive policing that discouraged her from coming forward earlier. She said: “I’m just a Mexican girl. I didn’t know who or where to turn to. The police pick me up all the time. That’s why I had to leave Houston. They beat me the last time.” Esperanza claimed that the police had “picked [her] up” and threatened her regarding her affidavit: “They told me they would put me in the penitentiary for making the statement saying I had lied at the trial.” Aurora Rodriguez, when approached by Chronicle reporters about the Pacheco case, gave a much shorter, but equally compelling, statement: “Homicide told me not to talk.”77

The affidavits of the Mexican American women, previously lauded as “key witnesses” whose testimony was vital to prosecution, were not significant enough on their own to reopen the case. HPD Chief Morrison only heeded their concerns when officer C. E. Marks, formerly with the Crime Prevention Bureau, expressed his doubts about the case. Marks explained to Morrison that his findings at the time had “differed with what the little girls had said from the witness stand,” which he told Judge King after the jury retired. King corroborated Marks’s claims when asked by the Chronicle but added that the officer’s conflicting testimony “wasn’t significant enough to alter the outcome” of the “puzzling case” and came too late to be of use to the jury.78

A Harris County grand jury investigation into the Pacheco murder case opened in late January 1953. Esperanza and Aurora Rodriguez were subpoenaed and arrested at a “night spot” on Liberty Road. The sisters were held in city jail for “safe-keeping” and were not released until the following night. Following their arrests, the Rodriguez girls claimed on the stand that they had been threatened into recanting their 1943 testimony by Julio Guerrero, confirming the claims of HPD Homicide Detective Brackenridge Porter. Esperanza had warned Franks of just this outcome. “If the police find me,” she told him. “I will make you no promise of what I will say to the grand jury.” Immediately after the sisters’ testimony, the grand jury announced that their investigation was completed, and they closed the case with no further action.79

In the wake of the Long-Haired Gang’s trial, local newspapers continued to report ethnic Mexican youths’ crimes and “street battles” through late 1943.80 A 1944 study by the Houston Council of Social Agencies found that youths of Mexican origin “were known to the police in much larger number than their proportion in the total population would indicate.” Mexicans comprised about five percent of the city’s population but thirteen percent of juvenile delinquency cases over the past five years. Mexican youths were also disproportionately institutionalized [End Page 383] when juvenile cases were taken to court, which historian William Bush attributed in part to the court’s “policy adopted of commitment of Latin-American boys to institutions” in response to the city’s panic over Mexican youth “gang warfare.”81

Houston LULAC faced significant criticism by city and county officials for “not doing more to prevent juvenile delinquency.”82 The pressure reached another crescendo following a week of alleged “juvenile gang warfare” in early July 1944 between Second Ward and Sixth Ward gangs. Detectives Crespo and Bell were assigned to “investigate the warfare,” and “12 juveniles, two youths and a 21-year-old woman” were initially arrested in connection with the “warfare,” which consisted of “shootings and rock battles,” with several juveniles allegedly wielding “blank pistols” and “wooden pistols” from “cruising cars.” At least one girl was injured when a stray bullet struck her foot, and a fourteen-year-old boy sustained unspecified injuries, although he was later arrested when he scaled the fire escape at the juvenile detention ward to talk to boys confined there. Another woman who was arrested was accused of providing guns to a juvenile involved in a shooting that occurred in the Second Ward.83

In response to the “flare-up” of alleged gang activities, the HPD formally announced that a “special squad” would specifically address Mexican youth gang crime. LULAC “vigorously protested” the proposed “Latin American” squad at a meeting at the Civil Courts Building, arguing that youth gangs were a result of high unemployment, proposing a plan to address the issue through recreational programs, and demanding that Mexican Americans be included on the squad. Despite such protests, the squad officially organized on July 15, 1944. In its first two months, it conducted 233 investigations that resulted in fifty-nine felony charges, including “one murder, two assault to murder, and 35 aggravated assault charges.” Additionally, the squad held 128 persons for investigations involving Latin Americans, filing an additional “28 charges of disturbing the peace, 16 affray charges, [and] 11 charges of carrying concealed weapons.” It also sent eight people to the FBI. Of the individuals “handled” by the squad, 113 were juveniles. The squad recovered seven pistols, one automobile, “other property valued at $2,100,” and seventy-two “marijuana cigarettes” from suspects. Crespo was the squad’s only Hispanic officer under the leadership of Lt. Bell.84 Newspaper reports indicate that the squad continued the HPD practice [End Page 384] of mass arrests of “Latin-American” youths through the rest of the year in their campaign to quash the alleged juvenile gangs of Houston.85

In October 1944, Crespo resigned as a detective. He gave no reason for the resignation, although it is possible that, as a public-facing business owner and civic leader, negative opinions within the Mexican American community played a role in his decision. But the damage had been done by the HPD, and by early 1945 Bell was reporting that the Mexican youth gangs had been eliminated.86 Careful examination of Houston Chronicle coverage illuminates the complexities of the city’s wartime Mexican youth gang panic. Whether the sensationalized concerns focused on unmasculine hair length or unregulated “skimpies,” policing the Mexican American youth’s gender and sexual expression led to the criminalization of pachucos and pachucas, and at least one miscarriage of justice in the Pacheco case. The hysteria over Mexican American young men’s “un-American” long hair prefigured the nationwide rise of courtroom “hair debates” in the 1960s and 1970s. Between 1965 and 1975, more than 100 “hippie” hair cases were appealed to U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeal, with nine reaching the U.S. Supreme Court. Debates raged over long-haired boys’ failures of “manliness and patriotism.”87 But in the 1940s, neither Mexican American girls nor boys were exempt from a crackdown that conflated juvenile delinquency with gender deviance. They experienced police violence, witness intimidation, and unfavorable depictions in the press. Ironically, prominent Hispanic civil rights leader Crespo led the HPD’s investigation into “Latin American cases.” Revisiting Houston’s Long-Haired Gang murder trial suggests that further study of the Mexican American juvenile delinquency panic might reveal still forgotten facets of this complex event, expanding perspectives on the Mexican American experience. [End Page 385]

Jordan M. Villegas-Verrone is a doctoral candidate at Columbia University. He received his bachelor’s degree from Harvard University. In 2024, he won the Louis Pelzer Memorial Award from the Organization of American Historians for his essay, “‘For the Girls’: Organizing Mexican American Girlhood in Depression-Era Texas.”

Footnotes

1. See, for example, Luis Alvarez, The Power of the Zoot: Youth Culture and Resistance in World War II (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008); Eduardo O. Pagan, Murder at Sleepy Lagoon: Zoot Suits, Race, and Riot in Wartime L.A. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003); Mark Weitz, The Sleepy Lagoon Murder Case: Race Discrimination and Mexican American Civil Rights (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2010); Edward Escobar, Race, Police, and the Making of a Political Identity: Mexican-Americans and the Los Angeles Police Department (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999).

2. Previous studies of Houston’s Mexican American youth gang panic during World War II include Arnoldo De Leon, Ethnicity in the Sunbelt: Mexican Americans in Houston (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2001); Thomas Kreneck, Del Pueblo: A History of Houston’s Hispanic Community (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2011); and William Bush, Who Gets a Childhood? Race and Juvenile Justice in Twentieth-Century Texas (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2010).

3. Pagan, Murder at Sleepy Lagoon, 10; Weitz, Sleepy Lagoon Murder Case, 33.

4. Luis Rey Cano, “Pachuco Gangs in Houston—A Postwar Phenomenon,” Agenda: A Journal of Hispanic Issues 9 (1979): 17–21.

5. See Elizabeth Escobedo, From Coveralls to Zoot Suits: The Lives of Mexican American Women on the World War II Home Front (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013) and Catherine Ramirez, The Woman in the Zoot Suit: Gender, Nationalism, and the Cultural Politics of Memory (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009).

6. De León, Ethnicity in the Sunbelt, 105–106.

7. “Mexican Boy Slain During Celebration,” Houston Chronicle, Sept. 17, 1942, section A: page 15.

8. “Police Instructed to Watch for Mexican Boy Gangsters,” Houston Chronicle, Sept. 25, 1942, B:2.

9. “Junior Gang Activities in City Being Probed,” Houston Chronicle, Jan. 11, 1943, A:9.

10. “New Jurors Told to Probe Juvenile Vice,” Houston Chronicle, Nov. 2, 1942, A:10.

11. “4 Mexican Boys are Committed to Training School,” Houston Chronicle, Dec. 29, 1942, B:11.

12. “Junior Gang Activities in City Being Probed,” Houston Chronicle, Jan. 11, 1943, A:9.

13. Bascom N. Timmons, Jesse Jones: The Man and the Statesman (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1952), 121–123, 376; Lionel V. Patenaude, “Jones, Jesse Holman,” Handbook of Texas, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/jones-jesse-holman [Accessed Mar. 9, 2025]; “Chronicle Personnel of the Highest Type,” Houston Chronicle, Feb. 22, 1938, C:2; “Always Stood for Clean Government,” Houston Chronicle, Feb. 22, 1938, C:10; “Accurate Reporting Praised by Allred,” Houston Chronicle, Feb. 22, 1938, C:2.

14. “Police Raid 30 Places in Gang Roundup,” Houston Chronicle, Jan. 17, 1943, A:14.

15. “Crime Bureau, Probation Forces Clash,” Houston Chronicle, Jan. 22, 1943, A:8.

16. “Purses Lost or Stolen, Gasoline Taken from Car,” Houston Chronicle, Jan. 22, 1943, B:1.

17. “Young Gangs Blamed for Crimes Here,” Houston Chronicle, Jan. 25, 1943, A:5.

18. “Boy Gangster, One of Last of ‘Black Shirt’ Gang, Is Sentenced,” Houston Chronicle, Feb. 2, 1943, A:12.

19. “3000 Attend Youth Council Rally in City,” Houston Chronicle, Mar. 15, 1943, A:4.

20. Cano, “Pachuco Gangs in Houston,” 17–21.

21. “Jury Told to Investigate Young Gangs,” Houston Chronicle, May 3, 1943, A:1.

22. Ramirez, Woman in the Zoot Suit, 69–70; Escobedo, From Coveralls to Zoot Suits, 22–23.

23. “2 Girls and Boy Get Jail Terms in Gang Assault,” Houston Chronicle, Sept. 23, 1944.

24. Marilyn Hegarty, Victory Girls, Khaki-Wackies, Patriots: The Regulation of Female Sexuality During World War II (New York: NYU Press, 2008); Escobedo, From Coveralls to Zoot Suits, 30–31; Ramirez, Woman in the Zoot Suit, 70.

25. Hegarty, Victory Girls, 32.

26. “Runaway Girl Problem Rises in Relations to Boys’ March to Camp,” Houston Chronicle, Feb. 11, 1941, B:1; Erik Carlson, “Ellington Field: A Short History, 1917–1963,” pp. 17, 4, NASA Oral History Project Records, Special Collections and Archives (Albert B. Alkek Library, Texas State University, San Marcos).

27. “County Reports Gain in Runaway Girls,” Houston Chronicle, July 21, 1941, B:7; “Boys Better; Girls Worse, Says Officer,” Houston Chronicle, Jan. 19, 1942, A:2.

28. “Liquor Board Chief Orders Ban on Carhops’ ‘Scanties’,” Houston Chronicle, Feb. 18, 1942, A:3.

29. Ibid.

30. “Runaway Girls, Stirred by Spring Wanderlust, Seek Adventure Here,” Houston Chronicle, Mar. 8, 1942, C:12.

31. “Campaign to Cut Venereal Disease Begun,” Houston Chronicle, Mar. 30, 1942, A:1.

32. “Policewomen Here Launch Drive on ‘Victory Girls’,” Houston Chronicle, June 23, 1943; Mitchel Roth & Tom Kennedy, Houston Blue: The Story of the Houston Police Department, (Denton: University of North Texas Press, 2012), 126.

33. “Sharp Upturn Seen in Child Delinquency,” Houston Chronicle, July 9, 1943, A:1.

34. “Policewomen Here Launch Drive on ‘Victory Girls’;” Roth & Kennedy, Houston Blue, 126.

35. “Harbeck will Carry on in Fight on V.D.” Houston Chronicle, July 18, 1945, B:15.

36. De León, Ethnicity in the Sunbelt, 109.

37. “Six Charged in Gang Slaying of Man Here,” Houston Chronicle, Mar. 26, 1943, A:1; “Texas Deaths, 1890– 1977: Jose L. Pacheco,” Family Search, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9B9N-SDC6?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AKS1G-BMP&action=view&lang=en [Accessed Mar. 9, 2025].

38. “Texas, Harris, Houston, Historic Hollywood Cemetery Records, 1895–2008: Jose L. Pacheco,” Family Search, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G93M-HWTZ?view=index&action=view&cc=2040173&lang=endigital [Accessed Mar. 9, 2025]; “Jose L. Pacheco,” Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/156434396/jose-l-pacheco [Accessed Mar. 9. 2025].

39. See, for example, in the months following Pacheco’s death: “Truck Driver Hurt When Hit by Train,” Houston Chronicle, Mar. 3, 1943, B:19; “Man Loses Leg When Struck by Train Here,” Houston Chronicle, Apr. 9, 1943, A:1; “Identification of Man Killed Here by Train Sought,” Houston Chronicle, June 29, 1943, A:1; “Retired Dentist Killed When Hit by Train in City,” Houston Chronicle, Aug. 14, 1943, A:1.

40. “Six Charged in Gang Slaying of Man Here,” Houston Chronicle, Mar. 26, 1943, A:1.

41. Kreneck, Del Pueblo, 45, 48

42. De León, Ethnicity in the Sunbelt, 109.

43. “Re. to Mr. L.D. Morrison’s Statement,” May 30, 1945, LULAC Council #60 Collection, Houston Metropolitan Research Center (HMRC), Houston Public Library, TX.

44. “Manuel Crespo Quits as City Detective,” Houston Chronicle, Oct. 12, 1944, A:1; “Two Mexico City Policemen Visit Police Station Here,” Houston Chronicle, Jan. 28, 1944, B:4; Thomas Kreneck, Interview of Manuel Crespo, Aug. 21, 1980, OH 298A, Oral History Collection, HMRC; Dwight Watson, Race and the Houston Police Department, 1930–1990: A Change Did Come (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2005), 111; Cano, “Pachuco Gangs in Houston,” 19. The first academy-trained ethnic Mexican police officer would not join the department until 1950. See Roth, Houston Blue, 300.

45. Kreneck, Interview of Crespo, Aug. 21, 1980.

46. Ibid.; “Two Tell of Seeing Man Beaten Here,” Houston Chronicle, Apr. 27, 1943, A:1; “Youth Acquitted in Slaying Here of Joe Pacheco,” Houston Chronicle, June 11, 1943, A:2.

47. Thomas Kreneck, Interview of Manuel Crespo, Jan. 8, 1988, OH 298B, HMRC.

48. “Six Charged in Gang Slaying of Man Here;” “Joe Pacheco’s Death Laid to Hemorrhage,” Houston Chronicle, Mar. 27, 1943, A:2.

49. “Six Charged in Gang Slaying of Man Here;” “Joe Pacheco’s Death Laid to Hemorrhage;” “Bond Set for 3 Accused in Gang Killing,” Houston Chronicle, Apr. 15, 1943, B:13.

50. Junior Gang Activities in City Being Probed,” Houston Chronicle, Jan. 11, 1943, A:9; O. W. Grow, “Keep in Trim with Our Armed Forces,” Barber’s Journal 45 (May 1942): 8–9 [cited in Obregon, Murder at Sleepy Lagoon, 101]; Ramirez, Woman in the Zoot Suit, 55–75.

51. Cano, “Pachuco Gangs in Houston,” 20; “Boy, 13, Shot, Men Stabbed; Gangs Sought,” Houston Chronicle, Aug. 18, 1944, A:2.

52. The Houston press seemed to associate the zoot suit with Black, not Mexican, criminality. See “Zoot-Suit Negro Shoots and Robs Man of $80 Here,” Houston Post, Mar. 17, 1943, A:1; “Negro Denies Robbery, Admits He Shot Driver,” Houston Post, Mar. 20, 1943, A:11; “Negro With Imperative Name Married Here,” Houston Post, Mar. 25, 1943, A:1; “Negro Seniors Hear Plea for Truth, Purity,” Houston Chronicle, June 2, 1943, A:10; “Zoot Suiter Seeks Altitude at Negro Dances,” Houston Post, Aug. 5, 1943, A:25. For more discussion of Black zoot suiters, see also Alvarez, Power of the Zoot. Only one instance of a local “long-haired Mexican” youth wearing a zoot suit was described in the local papers. See “Mexican Youths Stage Holdup at Ice Cream Store,” Houston Post, Jan. 22, 1943, A:2.

53. “Disinterment Applications, Houston, Texas, Historic Hollywood Cemetery Records, 1895–2008: Jose L. Pacheco, Family Search, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-8944-B8C6?view=index&action=view&lang=en” [Accessed Mar. 9, 2025]; “Joe Pacheco’s Death Laid to Hemorrhage;” “Grand Jury Gets Five Pacheco Cases,” Houston Chronicle, Mar. 30, 1943, B:9.

54. “Four Youths Billed in Pacheco’s Death,” Houston Chronicle, Apr. 2, 1943, A:1.

55. “Assault Robbery Case Sent Direct to Grand Jury,” Houston Chronicle, Apr. 3, 1943, A:7.

56. “Two of Gang Declared to be Juveniles,” Houston Chronicle, Apr. 9, 1943, A:15.

57. “Girl No-Billed in Pacheco Death Probe,” Houston Chronicle, Apr. 19, 1943, A:12.

58. “Six Charged in Gang Slaying of Man Here;” “Joe Pacheco’s Death Laid to Hemorrhage;” “Two of Gang Declared to be Juveniles;” “One of 6 Accused Youths Posts Bond,” Houston Chronicle, Apr. 13, 1943, B:9.

59. “Bond Set for 3 Accused in Gang Killing,” Houston Chronicle, April 15, 1943, B13.

60. Ibid.; “Record of Latin American Police Division is Cited,” Houston Chronicle, Sept. 17, 1944, D:9.

61. “Tom Guerrero Trial in Pacheco’s Death Starts in Local Court,” Houston Chronicle, Apr. 26, 1943, B:8.

62. Zarko Franks, “Youth Says Fear Made Him Confess,” Houston Chronicle, Dec. 30, 1952, A:7.

63. Zarko Franks, “Old ‘Murder’ Probe Pushed,” Houston Chronicle, Dec. 19, 1952, A:9.

64. “Two Tell of Seeing Man Beaten Here,” Houston Chronicle, Apr. 27, 1943, A:1.

65. Ibid.; “Cripple Gets 20 Years in Slaying Here,” Houston Chronicle, Apr. 28, 1943, A:4; “Boy is Jailed After Threat to Witnesses,” Houston Chronicle, May 1, 1943, A:3. For a discussion of the landmark Hernandez v. Texas decision, see Ignacio M. Garcia, White But Not Equal: Mexican Americans, Jury Discrimination, and the Supreme Court, University of Arizona Press (2008).

66. “Boy is Jailed After Threat to Witnesses;” “Threat Charge Against Mexican Youth Dismissed,” Houston Chronicle, May 25, 1943, B:4;“3 Accept Prison Terms in Killing of Joe Pacheco,” Houston Chronicle, May 10, 1943, A:1; “Two Convicted in Pachero Slaying Taken to Prison,” Houston Chronicle, May 15, 1943, A:3; “Tommy Guerrero is Sent Off to Prison,” Houston Chronicle, June 6, 1943, B:7.

67. “Jury Considers Murder Case of 15 Year Old Boy,” Houston Chronicle, June 10, 1943, A:5; “Youth Acquitted in Slaying Here of Joe Pacheco,” Houston Chronicle, June 11, 1943, A:2; Zarko Franks, “Youth Says Fear Made Him Confess,” Houston Chronicle, Dec. 30, 1952, A:7.

68. Ibid.; W. E. Robertson to Roy Hofheinz, Oct. 20, 1943, Vol. 534, p. 9, Juvenile Probation Department Records, Harris County Archives.

69. Watson, Race and the Houston Police Department, 111.

70. Cano, “Pachuco Gangs in Houston,” 18.

71. Zarko Franks, “Ex Detective to Testify in Old Murder,” Houston Chronicle, Jan. 23, 1953, A:7.

72. Zarko Franks, “Old ‘Murder’ Probe Pushed,” Houston Chronicle, Dec. 19, 1952, A:19.

73. Ibid.

74. Julio Guerrero and Pete Rodriguez, nos. 101351 & 101352, Conduct Registers, Convict Number Range B099640-101689, Volume 1998/038-231, Texas State Library and Archives, Austin.

75. Thomas Guerrero, no. 101461, Conduct Registers, Convict Number Range B099640-101689, Volume 1998/038-231, Texas State Library and Archives.

76. Zarko Franks, “Key Witness Puts New Doubt in 10-Year-Old Murder Case,” Houston Chronicle, Dec. 28, 1952, B:6.

77. Ibid.

78. Franks, “Old ‘Murder’ Probe Pushed.”

79. Zarko Franks, “‘Missing’ Witnesses to Testify,” Houston Chronicle, Jan. 26, 1953, A:10; Zarko Franks, “New Effort to Prove Innocence Pledged,” Houston Chronicle, Jan. 27, 1953, A: 20.

80. “Five Men Are Cut in Street Battle Here,” Houston Chronicle, June 30, 1943, A:3.

81. Bush, Who Gets a Childhood?, 49–50.

82. Cano, “Pachuco Gangs in Houston,” 20.

83. “Juvenile Gang Warfare Broken Up by Arrests,” Houston Chronicle, July 7, 1944, A:1; “Two Boys Facing Charges in Probe of ‘Gang’ Trouble,” Houston Chronicle, July 9, 1944, A:6; “11 Juveniles are Sent to State School,” Houston Chronicle, July 17, 1944, B:7.

84. Cano, “Pachuco Gangs in Houston,” 20; “Record of Latin American Police Division is Cited,” Houston Chronicle, Sept. 17, 1944, D:9.

85. See “Eight Boys Held After Exchange of Shots by Gangs,” Houston Chronicle, July 13, 1944, B8; “Ten Boys Beat Man at Farmers Market,” Houston Chronicle, July 15, 1944, 9;

86. “Manuel Crespo Quits as City Detective;” Cano, “Pachuco Gangs in Houston,” 20.

87. Gael Graham, “Flaunting the Freak Flag: Karr v. Schmidt and the Great Hair Debate in American High Schools, 1965–1975,” Journal of American History 91 (Sept. 2004): 523, 533.