The Alps as Lebensraum—Cinematic Representations of the Alpine War and the South Tyrol Question in 1930s Germany

This essay reads the mountain (war) films Berge in Flammen (The Doomed Battalion, 1931) and Standschütze Bruggler (Militiaman Bruggler, 1936) as cinematic renationalizations of the South Tyrol territory prior to and after the Nazi takeover. Alongside a flurry of publications in the early 1930s about the Alpine War by writers like Luis Trenker, Fritz Weber, and Anton Graf Bossi Fedrigotti, the films are influenced by the then rampant discussions concerning living space and pan-German geopolitics, including pressing questions about the Italianization of South Tyrol under Mussolini’s fascists. The genre of the mountain film was increasingly utilized to mobilize and militarize the German population.

Berge in Flammen (The Doomed Battalion), Luis Trenker’s account of his own war experiences in the Dolomites, reached cinemas in the autumn of 1931.1 The film triggered an enthusiastic response. The Berliner Börsenzeitung, for instance, praised the “magnificence of this truly patriotic film.”2 In the Lichtbildbühne, the critic Dammann wrote: “After a few seconds of a tear-filled silence, two hours of utmost suspense, excitement, aggravation find release in roaring applause.”3 The spirited defense of the Austrian homeland that the South Tyrolean Trenker depicted on celluloid stood in stark contrast to the candid antiwar films of the year prior that had portrayed the trench fighting in France. Both G.W. Pabst’s Westfront 1918 (1930) as well as Lewis Milestone’s All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) had exposed the war as senseless and anonymous mass death. In his autobiography Alles gut gegangen (All went well, 1965), Trenker acknowledges that he had seen the films himself, and they left him deeply dissatisfied. He writes: “All Quiet on the Western Front showed [End Page 61] the unholy futility of war alongside the self-sacrifice of a militarily drilled youth. No love for the fatherland, no virtue—there was nothing there. What remained was a deep, inconsolable emptiness.”4 Consequently, Berge in Flammen narrates a very different, personal war. Trenker’s film furnishes the void of its pacifist predecessors with values and content.

Following Eric Rentschler’s suggestion that mountain film “inhabits … a much wider discursive territory in the Weimar Republic”5 than what Siegfried Kracauer had assigned to the genre, I suggest that we could read Trenker’s Berge in Flammen and Werner Klingler’s Standschütze Bruggler (Militiaman Bruggler, 1936)6 as attempts to renationalize the South Tyrol territory as a traditionally German living space. I submit that these two mountain films, as well as Trenker’s subsequent Der Rebell (The rebel, 1932), not only popularized the Alpine War for German audiences, but that these productions ought to be considered responses to the annexation of South Tyrol after 1918 and the ensuing aggressive Italianization of the region under Mussolini’s fascists, in particular, men like Ettore Tolomei.7 Expanding our scope, I argue that the geographic struggles over South Tyrol are influenced by then rampant discussions concerning living space and geopolitics, discussions that we can trace back to intellectuals like Friedrich Ratzel, Halford Mackinder, and of course Karl Haushofer. Until the definitive 1939 South Tyrol Option Agreement between Hitler and Mussolini, the issue of South Tyrol remained a potential source of dispute between two fascist nations that were simultaneously trying to hammer out the extent of their cooperation.8 Within the geopolitical context of the time, mountain film thus morphed into a commentary on contemporary politics, whether with regard to the future of South Tyrol in a Greater Germany, or, if we think of a mountain/aviation film like Heinz Paul’s Wunder des Fliegens (The miracle of flight, 1935), with regard to the necessity of building up a German air force in defiance of the Versailles Treaty.9 One way or another, the popular genre of mountain film was increasingly utilized to mobilize and militarize the German population.

In May 1915, Italy declared war on the Habsburg empire following the signing of the Treaty of London. The secret pact between Italy and the Triple Entente was naturally intended to produce another ally in the fight against Germany and Austria. In 1915, the Italians were motivated to join the Allies because they desired to expand geographically. They were essentially the same imperial demands that had led Italy to enter into an alliance with its neighbors to the north in 1882. Back then, Italy was hoping for colonies. In 1915, the country had its eyes on territories closer to home. Of prime interest were the modern-day Italian provinces of Trentino, the Austrian coastal regions—including the ports of Trieste and Fiume (today Rijeka, Croatia)—and of course Tyrol up to the Alpine water divide at Brenner Pass. The promises of the Treaty of London pleased the adherents of irredentismo italiano, the nationalist movement that had engaged Italy since the late nineteenth century. The treaty promoted the final unification of large swaths of geographic areas in which Italian-speaking [End Page 62] populations formed a majority, or at least a sizeable minority. The irredentists understood themselves as completing the task of risorgimento, that is, the Italian unification that had fallen short in 1871 when Rome became the capital of the Kingdom of Italy. One year into World War I, the time to realize their dream seemed to finally have arrived. Joining the Triple Entente subsequently turned the Alps into a battlefield. When the dust of that war settled in 1918 with the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian empire, some 700,000 Italian mountain troops (Alpini) were dead. Another one million were wounded, including 700,000 disabled veterans. And due to the ensuing hardships of the war, approximately 600,000 civilians died as well. Altogether, the Italian death toll in and around the Alps reached a staggering 1.3 million.10

The Treaty of London eventually collapsed, partly due to the pressure of President Wilson’s Fourteen Points and his insistence on ethnic or national self-determination. As a result, not all of Italy’s territorial demands were met. The city of Fiume, ceded by Austria to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (later Yugoslavia), became a major bone of contention. The ensuing dissatisfaction with and critique of the liberal government led by Vittorio Orlando would fuel the next stage of Italian irredentism. Soon it would be the fascists’ turn to fulfill dreams of unification and conquest, pursuing the ultimate aim of an Imperium Latinum in the Mediterranean.11 The radical nationalist poet Gabriele D’Annunzio coined the term that would capture Italian sentiments vis-à-vis the war between Italy and Austria/Germany a century ago. For him, it was a vittoria mutilata—a mutilated victory.12 Just as the “stab-in-the-back myth” inspired the losers of the conflict in Germany to seek revenge, Italy’s “mutilated victory” would become a hallmark of fascist rhetoric after Mussolini’s rise to power in 1922. The Peace Treaty of Saint Germain, however, did award South Tyrol to Italy. This territorial transaction subsequently occupied the United Nations and the International Court of Justice in The Hague into the 1990s and led to the creation of the autonomous Euroregion of Tyrol-South Tyrol-Trentino in 1996, a construct that matches almost exactly the historical region of prewar Tyrol. In the years after the Alpine War, however, the South Tyrol question played itself out in a number of cultural manifestations, both texts and films, which are the concern of this essay.

Throughout the 1930s, we find several German articulations, both textual and filmic, of the de facto historical defeat and loss, which tell stories of triumph and perseverance in the early to mid 1930s. Berge in Flammen and Standschütze Bruggler present us with a curious blend of at least three genres: First, they clearly stand in the tradition of classic Weimar mountain films made by the inventor of the genre, Arnold Fanck. We find symptomatic elements of that genre in both films—shots of billowing clouds, snow-covered peaks, climbing and skiing, and a world framed by the dichotomies of struggle and redemption. Second, with their repeated emphasis on fighting, courage, comradeship, and duty for the nation, both films are clearly linked to war cinema. Third, there is the connection to the future Heimatfilm (homeland film) of the 1950s. After all, neither Trenker’s nor Klingler’s film emphasizes duty for [End Page 63] an abstract nation or state, but rather focus on the honorable defense of the Tyrolean homeland by German-speaking locals. And the homeland in both productions is Tyrol. Home is narrated in both films along archetypical opposites. For the 1950s Heimatfilm Johannes von Moltke identifies these opposites as questions of “home and away, tradition and change, belonging and difference.”13 The same opposites are prevalent in our films, and even more so in the literature preceding and accompanying them, as we will see below. Both Berge in Flammen and Standschütze Bruggler turn the Alps into culturally and ethnically German lands14 that face what a commentator at the time called “an Italian flood.”15 That both films reveal a certain overlap with these genres is not all that surprising, given that many of the film personnel remained the same for decades. The alpine cult figure Trenker, for example, rose to fame as a mountain climber in early mountain films by Fanck. In the late 1920s, he simultaneously began to produce and direct his own features. He occupied German television into the 1970s with series like Luis Trenker erzählt (Luis Trenker tells stories). Together with Klingler he made Wetterleuchten um Barbara (Sheet lightning for Barbara) in 1941, a propagandistic homeland drama that interpreted the 1938 annexation of Austria as a liberation of the Tyrolean people. The cameraman of Standschütze Bruggler and Wetterleuchten um Barbara, Sepp Allgeier, was an early assistant of Fanck. In the 1930s, Allgeier ended up filming for the lead protagonists of these early films, that is, for Trenker as well as Leni Riefenstahl, and Riefenstahl, in turn, made Allgeier lead cameraman for Triumph des Willens (Triumph of the Will, 1935).

At stake in Berge in Flammen is not a distant and impersonal front in far-away Galicia where the film begins and where the Tyrolean Rifle Regiments (Kaiserjäger) fight for the vast Austro-Hungarian empire in a conflict that can seem incomprehensible. Once the soldiers are transferred back to the Alpine front, their war makes sense, and their duty to fight for their emperor is paired with the motivation to endure in their defense of home and hearth. At peril are their homes, women, and farms, all of which are in plain view down below, yet at the same time far out of reach. Trenker plays the local climbing guide and then soldier Florian Dimai. He and his comrades have been holding the top of Coll’Alto (which, in real life and for Trenker, was the Lagazuoi). Their own families in the village below are enduring Italian occupation. Should the Austrians fail to defend the mountain, the foreigners will forever rule their village and homeland. It is a homeland that the Italians are literally undermining and destroying through the tunnels they are drilling. Unable to chase the Austrians off the mountain peaks, they attempt to blow off the tops along with the enemy. In the crucial final moments of Berge in Flammen, just before the explosion, we hear the ranking officer tell his men: “You know what is at stake. It is Tyrol, your homeland.” It will be up to Dimai to rescue his countrymen. He learns the exact time of the explosion during a perilous mission to the village. Only for a moment is he torn between staying with his wife and child and fulfilling his duty as a soldier. Heroically, Dimai delivers the [End Page 64] message on time and saves his men. After suffering heavy losses, the Austrians hold their position and persevere. The framing narrative of the film—an allusion to the climbing scenes of Weimar mountain films—leaves no doubt as to who is at home in Tyrol, and who is merely visiting. The beginning and end of the film point to the friendship between Count Franchini (Luigi Serventi) and his climbing guide Dimai. This friendship even survives the war during which Franchini occupies Dimai’s own house as an officer with the Alpini. In the beginning and end we see the Italian write in a tour book (in German) after a successful climb with Dimai. Twice we see him sign his name followed by his home. “Roma,” he writes. It is Rome where the Italian Franchini belongs, not Tyrol.

Clearly, around 1930 the stories of South Tyrol’s valiant resistance to annexation seemed increasingly opportune, irrespective of their actual historical setting. In the mid- to late 1920s, South Tyrol’s loss to Italy and its subsequent Italianization had led to an acute crisis.16 Trenker’s films about the conflicted region, whether Berge in Flammen or, in the year after, Der Rebell, in which Trenker revolts as Severin Anderlan against Napoleonic France, found a well-informed audience. Throughout the 1920s and across all political camps, shock was expressed over fascist acts of violence that had started with an attack on a procession in traditional local costume in Bolzano in 1921. The themes of subjugation, independence, and national uprising were the same in both of Trenker’s productions; and the audience had no trouble identifying them as references to the peace treaties that followed Germany’s and Austria’s defeat in 1918. However, Berge in Flammen comments only indirectly on a decade of forceful Italianization under the guidance of Tolomei’s 23-point program that reached a new high in 1930 when the Mussolini government encouraged thousands of southern Italians to relocate to the mountainous region in an attempt to reduce the local German-speaking population to minority status. In Trenker’s film, the war appears as an interruption of a natural order in which the Tyrolean people and their historical living space, reaching from the valley floor to precipitous heights, become temporarily severed. The Italians, occupying the valleys, long to storm the mountain peaks. The actual destination of the Tyrolean men atop becomes the now inaccessible valley. The realignment of space, people, and their natural trajectory is ultimately symbolized in the framing narrative. Scenes of Dimai guiding in his mountains open and close the film. Years after the war, Dimai, who has an established connection with his birthplace, once again brings the Italian visitor to the peaks of his homeland.17

The same year Trenker’s cinematic rendition of the Alpine War reached German audiences, he released two books in order to maximize distribution, interest, and financial profit: a novel with the same title18 as well as a richly illustrated version of the same story entitled Kampf in den Bergen. Das unvergängliche Denkmal der Alpenfront (Struggle in the mountains. The everlasting monument of the Alpine front).19 As it turns out, Trenker’s Alpine War troika of 1931 was the mere beginning [End Page 65] of a flood of publications concerning the 1915–1918 war in the Alps. In rapid succession, more titles recalled the efforts of Austrian and German troops to defend South Tyrol from annexation by the Italians. Trenker himself, at times aided by men like Walter Schmidkunz and Fritz Weber, followed up with Kameraden der Berge (Comrades of the mountains, 1932), Helden der Berge (Heroes of the mountains, 1935), Sperrfort Rocca Alta (Fortress Rocca Alta, 1938) and Hauptmann Ladurner (Captain Ladurner, 1940)—the latter introduced with a dedication to “the heroes of Narvik in comradely solidarity and as an acknowledgment of my gratitude and admiration of our common homeland.”20 All of Trenker’s publications ultimately confirm the supposed heroism of the Austrian and German troops that, side by side, defended their fatherland to the point of death. In so doing, Trenker also increasingly exhibits pan-German tendencies, finds meaning in the fighting, embraces the camaraderie of soldiers as an exemplary quality for those at home, describes mountain war as an adventure related to mountain climbing that tests manhood, and ultimately sounds rather like a South Tyrolean Ernst Jünger than a Remarque. By the time he publishes Hauptmann Ladurner in 1940, he can therefore easily connect Nazi Germany’s attack on Norway in the spring of 1940 with the fight in the Dolomites in, say, 1916. Locations, historical circumstances, and generations blend together into a celebration of duty and sacrifice for the all-German nation. The Alpine War becomes embedded in a tale about Germany’s decline that started with the defeat of Greater Germany in 1918 and saw a subsequent rebirth (and expansion) beginning in 1933. The “downfall” that included the loss of German territories like South Tyrol, and the natural alliance of German-speaking nations, Trenker muses, “has been avenged by the great deeds of the German Wehrmacht in the current war. The sons of those who back then fought and died in the Carpathian Mountains and on the peaks of the Alps are now playing their eternal part.”21

Hansjörg Waldner’s analysis of the book Berge in Flammen illuminates Trenker’s ideological indebtedness to the ever-growing nationalist discourse in the twilight years of Weimar Germany.22 Waldner compares editions before and after 1945. What he finds is a cleanup operation that purges scenes and phrases deemed unsuitable for a now democratizing audience. Removed is the dedication of the book that centered on war as adventure and that was rich in dramatic events worth telling, such as the many gallant deeds of individual Tyrolean soldiers trying to defend or liberate their village. Gone is the greeting “to all comrades, the mountains, and the homeland.” Instead, the preface for the 1971 edition lists a more affable motive for the publication of the book: “This is the tale of a friendship born in the mountains, a friendship that proved to be true through war and peace.” Removed is the scene where the newly recruited soldiers fuse into a homogenous unit by “solemnly” singing “Die Wacht am Rhein” (The guard on the Rhine), “the great German song” while the “regiment’s banner with the blood-red eagle, glorious and shredded … is waving above their heads” (Flammen, 48). Gone are also the “Jews in their black caftan” who were loitering [End Page 66] around in Galicia and who “greeted us full of canine devotion” (Flammen, 54). Not unlike Jünger’s In Stahlgewittern (Storm of Steel, 1920), Trenker captures the ensuing anonymous fighting and dying on a large scale in a language that describes war as a natural event: “Tirelessly, the Russians hurried their masses against the Carpathian Wall. It roared toward us like the eternal tide in dark waves, frothed up, flowed back in blood” (Flammen, 68). In the midst of this natural spectacle of flooding and damming comes the news that Italy has declared war on Austria. The anonymous, alienating, and unintelligible war in Galicia, where Dimai and his Tyrolean men served loyally but ultimately without true purpose, becomes personal. Now women, home, and farm are at stake. Dimai has a vision upon hearing the news:

He does not see or hear the others. As if seeing a vision, he notices heavy black smoke, hears the drone of the machinery of war grinding everything that is alive to a pulp … and sees how the fires are spreading, how the forests are burning, how the mountains are glowing, he sees everything ablaze, the homeland, his happiness, his mountains.

(Flammen, 70)

In the ensuing tale of homeland defense, Trenker does not tire of stressing the values of camaraderie, loyalty and discipline. His mountains, his family, and his homeland provide him with an arsenal of highly personal motives. The fictional hero Florian Dimai is never far removed from the war hero Luis Trenker. Both are embedded in a value system that ultimately embraces war and its virtues as fundamentally heroic. War appears as an unpleasant but necessary interruption of an alpine existence already characterized by loyalty, devotion, comradeship, suffering, and death. Especially when one compares Trenker’s war stories with other texts that recall his days as a mountain guide among other locals, one cannot help but notice that the climbing men of the mountains already carried within themselves the very qualities needed to become mountain warriors. Paradigmatic for this fusion is the chapter “Comrades” in his 1932 publication Kameraden der Berge (Comrades of the mountains).23 We read there that “the mountain guide comrades became war comrades,” and that “most of us were initially sent to the Russian front, and many stayed there forever, buried, never again seeing their homeland and mountains” (Kameraden, 188). The chapter mixes childhood memories of “Stainer Wastl” (“bled to death as a young volunteer in the dirt and sludge of the Zalescicki bridgehead”) and recollections of early climbing days with Hans Pescosta (“In his eyes the luster of happiness and the will to fight.” Pescosta, we read later, also bleeds to death on the battlefield) as does Hans Dülfer (“fallen near Arras”); the chapter includes war memories concerning local guides and friends like “Zenzl,” “Prugger,” and “Fussenegger”—all of them eventual victims of the war. In fact, what fuses all these mountain men into a brotherhood, or rather a community of death, is their shared experience of suffering and loss. Upon the news that “the great German fatherland had collapsed” (Kameraden, 194),24 Trenker turns [End Page 67] to this pantheon to find meaning in these years of agony in camaraderie. Trenker writes: “Each one of these men had become acquainted with purgatory, had endured, sacrificed, and suffered everything a human being can for four years … Each one of these men became a symbol of camaraderie for me.” When it is time to depart, when it is time to return to a Tyrolean homeland that, despite everything, is no longer theirs, an emotional good-bye seals the eternal loyalty with a handshake: “Fighting down the rising tears I shake the loyal, hard hands for a final farewell” (Kameraden, 195).

The remainder of “Comrades” then looks back at the years since 1918. Those years were filled with activities not fueled by passion or vocation, but by rather pragmatic reasons—and in dubious company: “I jumpstarted an architecture business in Bolzano while struggling against public authorities, fat cats and petty bourgeois” (Kameraden, 196), Trenker writes. Yet the mountains away from philistines and city folk keep calling. The connection with Arnold Fanck’s Sportfilm G.m.b.H. has the pleasant effect that it brings Trenker back in touch with “all those comrades from days gone by” (Kameraden, 197). He lists, among others, the veterans Hans Schneeberger, Sepp Allgeier, and Hannes Schneider: “More and more I wanted to get away from the office” (Kameraden, 198). Filmmaking provides an escape. And what’s more, making mountain films requires the same tough qualities of those men who only a few years prior held rifles instead of ice picks: “We were suffering from the cold, from thirst and hunger. Tired and excoriated we threw ourselves onto the wooden cots of our huts” (Kameraden, 198). What Trenker portrays here is not war, yet it might as well be. The fabled front community evolves, or sees itself reborn, as a film crew high above and far away from the bustle of the modern city and its bourgeois inhabitants: “A team spirit developed gradually amongst my companions. We are in the midst of creating something. It was a long journey from Mountain of Destiny to Fight for the Matterhorn to The Doomed Battalion. We have been forged into an ever-stronger circle by enduring the worries, hardships, and dangers together.” The book ends in a mantra one might not be surprised to hear repeated by Riefenstahl’s columns of workers in Triumph of the Will: “And we want to continue to remain comrades of life, comrades of labor, comrades of the mountains” (Kameraden, 200).

War, climbing, and filmmaking thus turn in the early 1930s into an amalgam that would continue to haunt Germany for years to come, whether on the north face of the Eiger or on Germany’s so-called mountain of destiny, the Nanga Parbat. In 1938, the year of Trenker’s most famous film, Der Berg ruft (The mountain calls), as well as Austria’s annexation, Trenker could not abstain from tooting his own horn once more, reminding his readers that the filmmaker and star of Der Berg ruft was a war hero before he became a film star. A comment at the end of Trenker’s Sperrfort Rocca Alta recalls Trenker’s and Fritz Weber’s deeds in wartime when they had served together in the fortification of Verle: “The officer cadets Weber and Trenker in Verle have proven that it is possible to endure the impossible, to do the unimaginable. With [End Page 68] courage, self-confidence, and faith in the Austrian soldier, one can, if necessary, even exorcise the devil from hell.”25 In the year of Austria’s annexation—the resurrection of Greater Germany—we might wonder what unbelievable deed Trenker may have had in mind. Was he perhaps thinking of South Tyrol’s liberation and return to Austria?

Beginning with Trenker’s film, a host of publications concerning the Alpine War emerged in close succession during the 1930s, at times with Trenker’s involvement. Alongside a general boom of wartime memories, the struggle concerning South Tyrol became a habitually recalled issue. To name a few publications: in 1932, Gunther Langes’ Die Front in Eis und Fels. Der Weltkrieg im Hochgebirge (The front in ice and rock: The First World War in the high mountains) appeared. The same year saw the publication of Fritz Weber’s Feuer auf den Gipfeln (Fire on the peaks) and Georg Freiherr von Ompteda’s Bergkrieg (Mountain war). In 1934, Weber followed up with Alpenkrieg (Alpine war) as well as a reprint of a title that had already appeared in the 1920s, Frontkameraden (Front comrades), with a chapter on Trenker. Christian Röck published Die Festung im Gletscher (The fortress in the glacier) in 1935 with an introduction by Trenker. Finally, in the year Standschütze Bruggler is made, 1936, Gustav Renker reached deep into his past by publishing the Kriegstagebuch eines Bergsteigers (War diary of a mountain climber). Renker, hired by the military as an advisor familiar with the mountains, had already sent reports from the Alpine front during the war in the Zeitschrift des Deutschen und Österreichischen Alpenvereins (Journal of the German and Austrian Alpine Club).26 What can we make of this abundance of publications in the first half of the 1930s, both before and after the Nazi takeover? As stated above, I consider the political context to be one of decisive importance, in particular the prospective return of Austria within a pan-German alliance, as well as the connected issue of South Tyrol’s potential inclusion into Germany/Austria. As my analysis of some of Trenker’s works shows, what prevails amidst general reflections of bravery, duty, and sacrifice are deliberations concerning South Tyrol as part of a traditionally pan-German homeland. Fritz Weber’s works support this claim. In Trenker’s war friend and collaborator Weber, we find an even stauncher vision of an ethnocentric and even racist nationalism in defense of a historical (if not natural) German living space.27 Trenker’s Berge in Flammen renationalizes the South Tyrol question for an audience eager to lick its wounds, keen to undo the alleged wrongs of the peace treaties of 1919. And the film does so at a time when Mussolini’s Italy significantly escalates the pressure on South Tyrol’s inhabitants by attempting to alter the age-old demographics of the region. I therefore do not share Waldner’s conclusion that the final scenes of Berge in Flammen, those that show Franchini and Dimai climbing together after the war, ought to be understood as “propaganda for the political pragmatism of the heralded alliance between Germany and Italy.”28 For one, in 1931 there is little de facto cooperation to be found between the two potential allies that share only a common disdain for democracy and liberalism. Second, after [End Page 69] 1920 Austria’s First Republic was dominated by the anti-Anschluss and antirevisionist Christian Social Party. The 1932 takeover by Engelbert Dollfuß brought no change for South Tyrol because Dollfuß was a close ally of Mussolini and never tired of pointing out the similarities between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. Mussolini, in turn, perceived Austrofascism to be a desirable buffer between Italy and Germany. And third, the pan-German fantasies attached to an imagined Nazi takeover in Germany, followed by the ensuing revival of a new empire, did not leave room for a South Tyrol under Italian control.

With the Nazis firmly in charge, and with widespread talk of bringing all Germans home into the Reich, an Austrian annexation seemed ever more likely, especially after the 1934 assassination of Chancellor Dollfuß. The release of Standschütze Bruggler in the summer of 1936 came at a time when relations between Germany and Italy were only beginning to crystallize into a lasting cooperation.29 The central component of this warming trend between Hitler and Mussolini was an agreement regarding Austria. In the so-called “July Agreement,” Italy announced the end of its investment in Austrian politics. Mussolini finally acknowledged that Austria was primarily a German country. He would no longer stand in the way of Austria’s domestic politics or its foreign affairs, which meant only one thing: Austria’s eventual union with Nazi Germany. But a future union would bring the Nazi military machine all the way up to Brenner Pass. Was the time ripe in 1936 for German (cinematic) calls to return South Tyrol to a future Greater Germany?

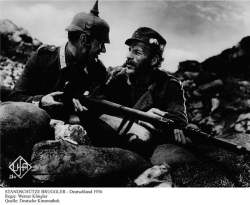

Klingler’s Standschütze Bruggler is an adaptation of a novel with the same title by Anton Graf Bossi Fedrigotti of the year 1934.30 Fedrigotti was an Austrian diplomat, author, SA, and party member. He dedicated much of his work to South Tyrol and its struggles and disseminated his revanchist leanings in a number of publications. His 1934 novel, Standschütze Bruggler, is one such example. Written in diary form, it recounts the story of sixteen-year-old Tyrolean volunteer Anton (Toni) Bruggler, who is initially destined to become a priest, yet finds his true calling in serving his country in its fight against Italy. At the end, the reader understands that the hero of this war diary is dead, fallen on the battlefield for a German Tyrol in 1916. It is his teacher Bauer who hands the manuscript to a general’s widow whom Bruggler had befriended during the war. In his correspondence, Bauer points out how “a single year of war” had elevated Bruggler “to a German man” (Bruggler, 431).

Fundamentally, Bruggler’s observations and actions are guided by a völkisch-national ideology.31 The village priest addresses right and wrong from the get go:

“If someone suddenly wanted to take your farms from you to give them to someone else, farms on which you have been sitting for centuries, you, too, would fight back,” he preaches. “And it’s the same with the Italians … they want to take our villages … and to turn us into the same poor people like the farmers across the border in Comelico and Cadore have been since 1866.”

(Bruggler, 11) [End Page 70]

Tyrol, it is clear, has to remain German. Toni states: “We all revered the old Emperor in Vienna. He really didn’t have to call for us. We would have gone anyway to keep our homeland German.” (Bruggler, 13). Throughout the text, German people are shown to be superior, more reliable, more heroic, or simply better than their Slavic allies. Only the Tyrolean Germans will defend their homeland with the required bravado and skill. Toni again: “Wherever we Germans are amongst ourselves we are safe. But should the people that already ran away in Galicia be deployed here as well, it will not look good for the defense of our country” (Bruggler, 37). In a nutshell: “German together with German is good” (Bruggler, 38). The film stresses this alliance at its crucial climax when troops from the German empire arrive at the last moment during an Italian assault. Guided to the front by Bruggler himself, the German-Austrian closing of ranks that repels the attack is literally emphasized in a close-up on the movie screen when both respective commanders fight side by side. The text never tires of stressing the supremacy of all things German: “Germans, stand together!” (Bruggler, 379) is the battle cry of Zugführer Obwerer toward the end of the story when the traditional German homeland needs to be defended against the Italian assault.

Obwerer’s holler might well sum up the sentiment of another Fedrigotti publication of the period. In 1935, one year after Standschütze Bruggler, he produced Tirol bleibt Tirol. Der tausendjährige Befreiungskampf eines Volkes (Tyrol remains Tyrol. The [End Page 71] 1000-year-old struggle for the liberation of a people).32 In this collection of seventeen historical vignettes, Fedrigotti revisits what he considers to be an epoch of German tradition in South Tyrol: “a German millennium” (Tirol, 18). The stories are framed by the present-day Italian occupation, against which the South Tyroleans rally. In the opening vignette, for instance, Fedrigotti has the youth of the Sexten Dolomites light huge fires high up on the mountain slopes. To the chagrin of the Italian occupation forces, the flames spell out: “Tyrol remains Tyrol” high above the villages. Rebellion is in the air: “You may be able to extinguish those flames over there—but you can never extinguish the flames in the rocks and within our hearts!” (Tirol, 9). In a hodgepodge of mythical origins, Wotan, Odoacer, and the Germanic tribes are all mobilized. The historical parallels, including those Johann Gottlieb Fichte rallied against in his Reden an die Deutsche Nation (Addresses to the German nation, 1808) are easy to comprehend. What the Romans were in antiquity, and what the French were during Napoleonic supremacy, the Italians are today. The “native inhabitants of the mountains” (Tirol, 12), the “original people” (Tirol, 14) are ultimately of German origin, and throughout the centuries, Germans resisted all attempts to remove them from their ancestral lands. The last two chapters of the collection, “World War” and “Finale,” bring the reader into the present. The organizing principles of the narrative resemble those of the Kampfzeit (Hitler’s rise to power) further north, or the choreography of the opening sequence of Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will, the epos of the new order: betrayal, suffering, redemption, and rebirth.“The Tyrolen soldier is holding the front, quietly doing his duty to the very last day of the war,” and “the German-Austrian” especially is keeping his calm when Hungarian divisions of the multiethnic empire refuse to fight (Tirol, 261). The alpine troops leave the battlefield “unbeaten” and with “their heads held high” (Tirol, 261). They are filled with the unshakeable belief that Germany is going to come to the rescue of the Germans of Tyrol. Yet, that never happens. Instead, Tyrol is seemingly surrendered, handed to the Italians at Saint Germain. For Fedrigotti this is the ultimate treachery: “Never in the history of mankind was a people more profoundly disappointed and were a people’s ultimate hopes more bitterly betrayed than the German people of Austria in November 1918. And alongside with them the Tyroleans” (Tirol, 262). Bled dry after years of fighting on numerous fronts, neither country is in a position to defend the “German soil” (Tirol, 262) against Italy. With the Habsburg monarchy gone, a resilient Tyrol nonetheless has been committed since 1918 to its age-old “Germandom” (Tirol, 265).

The final section, “Finale,” presents the reader with a mix of self-pity about Saint Germain, where South Tyrol was “shackled” and where its “suffering” (Tirol, 266) began, and the promise of a “struggle” (Tirol, 274) for Tyrol’s homecoming. Fedrigotti recalls Italy’s measures against “the German customs” (Tirol, 269), the ongoing “De-Germanization” (Tirol, 269) of the region. “There is not one law … and not one decree, no measure and no change that would not be employed in South [End Page 72] Tyrol against the indigenous German population” (Tirol, 269), Fredrigotti laments, evoking the values of blood and soil. The Italianization campaign under the fascists threatens one of the “historically most German parts” (Tirol, 268) and could eclipse Tyrol’s farmers. Is the “destruction of the German farmers” a foregone conclusion? Are Italy’s “de-Germanization efforts” (Tirol, 273) irreversible? Clearly, Fedrigotti thinks, or at least hopes, otherwise. In 1935, two years into the new Reich up north, a new fighting spirit has emerged in South Tyrol, a “nascent resistance” and “dam” (Tirol, 273) that, it seems, is only waiting to burst and flood toward the “stream of German life” (Tirol, 274). What continues to beckon the people of South Tyrol is their desire “to return home to the German empire” (Tirol, 273). The text ends on a quasi-religious note, imagining a salvation woven into a future all-inclusive German unity as the Promised Land:

Three elements are the everlasting guarantors for this day of salvation. The eternal Tyrolean mountains, the dead resting within them, and the living community for which Tyrol’s mission did not begin only yesterday, that will not be finished today, and that will not end tomorrow. For Tyrol’s mission is as eternal as the bloodstream it serves.—The German Volk!

(Tirol, 274)

In the film, the audience accompanies Toni Bruggler on his journey from theology student to dedicated soldier. Unlike in Fedrigotti’s book, in the film, Toni Bruggler survives. He becomes the ultimate hero when, after bolting from Italian captivity, he leads the German troops to the battlefield just in time to repel the decisive Italian attack on the Austrian positions. During the victory celebration that concludes the film, he receives a medal for his heroism. When prompted by the general as to what will be next, we hear him exclaim in a close-up: “I will remain a soldier!,” his face beaming with pride and vocation. Even his initially skeptical mother, now the envy of the womenfolk in town, could not be more proud. Originally, Mother Bruggler had opposed her son’s desire to abandon his studies and defend their homeland alongside the other local militiamen. Throughout the film, she repeatedly tries to convince her son that he should take advantage of his theology studies, as they exempt him from military service. The film stresses early on that she had lost her husband, a member of the Tyrolean Rifle Regiments, on the eastern front at the beginning of the war, and that her motivation is understandable fear for her son. The father’s picture, showing him in uniform, is hanging on the wall. In one of the film’s first scenes, Toni is shown looking at the image longingly and filled with admiration. Yet, eventually Mother Bruggler will come full circle, embracing her son’s future on German battlefields.33 True to fascist form, individual desires and inclinations must be subordinated to a higher order.

In 1936, Standschütze Bruggler does more than merely recall the Alpine War as [End Page 73] the heroic struggle of underequipped but dedicated Tyrolean militiamen. The film comments throughout on the fundamentally German ethnic or racial roots of the territory. The Italians are outsiders and invaders without any historical connection to the lands they attempt to conquer. However, the film undertakes this endeavor without demonizing the Italian adversary. Instead, it leaves the opponent rather featureless. At the already mentioned climax of the film, when German troops, marked by their spiked helmets and northern accents, arrive towards the end to rescue the militiamen of Hochbrunn, when they together throw the Alpini off the mountain, we have to assume that these scenes of all-inclusive German unison and military might are meant to send a message to Mussolini. After all, the alliance between the Austrian and German commanding officer on the movie screen in 1936 will become political reality a mere two years later with the appropriation of Austria. Standschütze Bruggler allows Nazi Germany to flex its muscles towards Rome at a politically critical juncture. It does not require too much imagination to ponder whether the return of the Alpine Germans in South Tyrol was on Hitler’s wish list, despite all assurances to the contrary. Nevertheless, the fact that Standschütze Bruggler does not make an all-out case for South Tyrol’s impending return to Germany has to do with the complicated (geo)politics surrounding the region.

Hitler’s comments on South Tyrol in chapter 13 of Mein Kampf (My Struggle) are well known.34 They prove, at least in part, useful for untangling the issue. On the one hand, Hitler leaves no doubt that South Tyrol is German—that it was betrayed and then dishonestly taken by Italy. The “return of the lost provinces,” if need be “by means of war” is a priority for him. From Landsberg prison, he writes: “As far as I am concerned I can certainly guarantee you that I would be courageous enough to lead a battalion of storm troopers … to help conquer South Tyrol” (Struggle, 708). On the other hand, the realpolitik of Nazi Germany’s geopolitical ambitions requires strategic alliances down the road, and fascist Italy is, at least in theory, an early contender: “It is quite obvious why, in recent years, certain circles have made the ‘South Tyrol Question’ the sine qua non of German-Italian relations. … It is not because of love for South Tyrol that today so much fuss is being made,” he writes in 1923, “but rather because one is afraid of a potential German-Italian agreement” (Struggle, 709). The cooperation between these two states, however, repeatedly experienced severe complications during the late 1920s and early 1930s. Examples include the Italianization of South Tyrol, the murder of Dollfuß in Austria, and the Nazi racial policies that emphasized a nordicist conception of the Aryan race. Throughout the early 1930s, competing interests in the Danube regions, especially concerning Austria, markedly strained the relationship between the two countries. Mussolini observed the rise of Nazi Germany with a mixture of fear and admiration. While Hitler’s ascent aided Mussolini’s desire to expand Italian territory, he also had cause to fear the potential backlash on southeastern Europe, especially Austria and [End Page 74] South Tyrol.35 When the two leaders finally met for the first time in the summer of 1934, Hitler wasted no time in raising the issue of Austria, yet Mussolini resisted his advances. No matter how close both countries were in ideological terms, they could not bridge their respective geopolitical interests. The murder of Dollfuß only weeks later significantly worsened the relationship. In his detailed analysis of the genesis of the axis, Jens Petersen speaks of a “rapid climate deterioration.”36 In the context of Italy’s campaign against Ethiopia, the Second Italo-Abyssinian War in 1935–1936, Italy itself needed to improve relations with France, which in turn further cooled relations with Germany. However, in 1936, around the very time Klingler’s film was in the theaters, the dealings between both countries slowly became more amicable. Most importantly, Mussolini and Hitler finally agreed on Austria, and Mussolini furthermore signaled a quiet endorsement concerning the occupation of the Rhineland. Increasingly, both men revealed ever more lucidly their shared desire to overcome the agreements of Versailles and Locarno, and to change the status quo. In addition, the Italian leader decided to launch a racial program in Italy under Giulio Cogni who, impressed by Nazi racial theory, published Il Razzismo in 1936. The previous focus on Italy’s Mediterraneanism was now gradually replaced by a focus on nordic Aryanism. The Duce’s fear about German intentions in South Tyrol were eventually pacified by a deal between both dictators that was guided by the strategic need to preserve good relations: the South Tyrol Option Agreement in 1939 gave the German speaking population the choice to either emigrate or accept complete Italianization. For pan-German men like Fedrigotti, who had worked hard to return South Tyrol to Greater Germany, it was the ultimate disappointment. Following a thorough propaganda campaign by the Nazis, more than 80% of the population opted to leave South Tyrol for Germany.37 It seemed that the territory was finally going to become a part of what Italian fascists referred to as their spazio vitale—vital space. The cinematic renationalization of South Tyrol in Trenker’s and Klingler’s films that unfolded in the 1930s, alongside a host of publications recalling the Alpine War, emerged at a time when the future of South Tyrol seemed, once again, open for change. Both films succeeded in keeping the formerly German territory on the mental map of all those who harbored revanchist tendencies, thereby turning mountain film into a continuation (or expansion) of politics through cinematic means.

wilfried wilms (wilfried.wilms@du.edu) is Associate Professor of German Studies at the University of Denver and editor of German Postwar Films (2008) and Bombs Away (2006). His work has appeared in Deutsche Vierteljahrsschrift, Monatshefte, Colloquia Germanica, and other journals. This article is part of his current research on mountain film and the militarization of alpinism after World War I.

Notes

1. I discuss Trenker’s rendering of vigorous masculinity in Berge in Flammen and elsewhere in “From Bergsteiger to Bergkrieger: Gustav Renker, Luis Trenker, and the Rebirth of the German Nation in Rock and Ice,” Colloquia Germanica 42, no. 3 (2009): 229–244.

2. Anonymous, “Berge in Flammen,” Berliner Börsenzeitung, Sept. 29, 1931. This and all following translations from the German and Italian are my own.

3. F. Dammann, “Berge in Flammen,” Lichtbildbühne, Sept. 29, 1931.

4. Luis Trenker, Alles gut gegangen. Geschichten aus meinem Leben (Hamburg: Mosaik, 1965), 260. [End Page 75]

5. Eric Rentschler, “Mountains and Modernity: Relocating the Bergfilm,” New German Critique 51 (1990): 137–161, here 142. Rentschler’s thoughtful criticism of Kracauer’s “one-way street from the cult of the mountains to the cult of the Führer” (145) has brought about innovative scholarship as well as a revival of mountain film itself with recent German productions like Nordwand (North Face, 2008) and Nanga Parbat (2010).

6. Together with Luis Trenker, Klingler will later also codirect the comedic mountain film variant Liebesbriefe aus dem Engadin (Love letters from the Engadine, 1938).

7. On South Tyrol, see Rolf Steininger, South Tyrol. A Minority Conflict of the Twentieth Century (Brunswick, NJ: Transaction, 2003).

8. For a detailed analysis of the genesis of the axis, see Jens Petersen, Hitler-Mussolini. Die Enstehung der Achse Berlin-Rom 1933–1936 (Tübingen: Niemeyer, 1973).

9. On the role of aviation in Die weisse Hölle vom Piz Palü (The White Hell of Pitz Palu, 1929), Stürme über dem Montblanc (Storm over Mont Blanc, 1930), and Wunder des Fliegens (Miracle of flight, 1935), see my essay “Regaining Mobility: The Aviator in Weimar Mountain Films,” in Crisis and Continuity. German Cinema 1928–1936, ed. Barbara Hales, Mihaela Petrescu, and Valerie Weinstein (Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2016): 167–186.

10. The Austro-Hungarian dead, missing, and wounded are estimated to be approximately 650,000. For a detailed history of the Alpine War emphasizing the Italian side, see Mark Thompson, The White War. Life and Death on the Italian Front 1915–1919 (New York: Basic, 2008), here 381. See also Tait Keller, “The Mountains Roar. The Alps during the World War I,” Environmental History 14, no.2 (2009): 253–274.

11. D’Annunzio, for instance, was one of the first to act. In September of 1919, he led several thousand troops into Fiume and occupied the city for over a year. In particular, the eventual failure to hold on to Fiume and sole control of the Adriatic Sea gave rise to the idea of a mutilated victory.

12. Gabriele D’Annunzio, editorial in Corriere della Sera, Oct. 24, 1918.

13. Johannes von Moltke, No Place Like Home. Locations of Heimat in German Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 3.

14. On the shared Alps as a cultural platform for Austrian and German cinema and identity politics around the time of Austria’s annexation, see Robert von Dassanowsky, “Snow-Blinded. The Alps contra Vienna in Austrian Entertainment Film at the Anschluss,” Austrian Studies 18 (2010): 106–123. Dassanowsky’s study illustrates how plot and characters of films like Konzert in Tirol (Concert in Tyrol, 1938) ultimately work to eradicate Austrian difference. An ethnic German community is unified on the screen by “shifting the centre of culture from Vienna to the shared Alps” (111). Film uses “imagined ethnic communities and regions to eradicate the ‘illusory’ political borders between Austria and Germany” (112).

15. Gustav Renker, “Der Krieg in den Bergen,” Zeitschrift des Deutschen und Österreichischen Alpenvereins 47 (1916): 219–236, here 219.

16. See Petersen, Hitler-Mussolini, esp. 497.

17. On Berge in Flammen, see Christian Rapp, Höhenrausch. Der deutsche Bergfilm (Vienna: Sonderzahl, 1997), 157–178.

18. Luis Trenker, Berge in Flammen (Berlin: Knaur, 1931). The edition I am using is a 1940 reprint. Hereafter cited parenthetically in the main text using abbreviated title Flammen and page number.

19. Luis Trenker, Kampf in den Bergen. Das unvergängliche Denkmal der Alpenfront. Illustrierte Ausgabe des Buches “Berge in Flammen” (Berlin: Neufeld & Henius, 1931).

20. Luis Trenker, Hauptmann Ladurner. Ein Soldatenroman (Munich: Eher, 1940); Luis Trenker, Sperrfort Rocca Alta. Der Heldenkampf eines Panzerwerkes (Berlin: Knaur, 1938); Luis Trenker, Helden der Berge (Berlin: Henius, 1935); Luis Trenker, Kameraden der Berge (Berlin: Wegweiser, 1932). A later book entitled Tiroler Helden (Berlin: Knaur, 1942) extracts war-related stories from Helden der Berge.

21. Trenker, dedication of Hauptmann Ladurner, 5, written in June 1940. [End Page 76]

22. See Hansjörg Waldner, “Deutschland blickt auf uns Tiroler,” in Südtirol-Romane zwischen 1918 und 1945 (Vienna: Picus, 1990), esp. 54–65.

23. Hereafter cited parenthetically in the main text using abbreviated title Kameraden and page number.

24. This sentence is gone from the 1970 edition of Kameraden der Berge.

25. Luis Trenker, Sperrfort Rocca Alta, 268.

26. For example “Der Krieg in den Bergen,” Zeitschrift des Deutschen und Österreichischen Alpenvereins 47 (1916): 219–236 and “Bergtage im Felde. Tagebuchblätter von Dr. Gustav Renker,” Zeitschrift des Deutschen und Österreichischen Alpenvereins 48 (1917): 177–200. In 1918, Renker published a monograph detailing his exploits. Renker, Als Bergsteiger gegen Italien (Munich: Schmidkunz, 1918).

27. See Christa Hämmerle’s excellent analyses “‘Es ist immer der Mann, der den Kampf entscheidet, und nicht die Waffe.…,’” in Der Erste Weltkrieg im Alpenraum. Erfahrung, Deutung, Erinnerung, ed. Hermann J.W. Kuprian and Oswald Überegger (Innsbruck: Athesia, 2006), 35–59. Also by Hämmerle: “‘Vor vierzig Monaten waren wir Soldaten, vor einem halben Jahr noch Männer.…’ Zum historischen Kontext einer ‘Krise der Männlichkeit’ in Österreich,” L’Homme. Europäische Zeitschrift für feminisitische Geschichtswissenschaft 19, no.2 (2008): 51–73.

28. Waldner, “Deutschland blickt auf uns Tiroler,” 65.

29. Petersen, Hitler-Mussolini, esp. 481–483.

30. Bossi Fedrigotti, Anton Graf, Standschütze Bruggler (Berlin: Zeitgeschichte Verlag, 1934). Hereafter quoted parenthetically in the main text using abbreviated title Bruggler and page number.

31. Frequently, the reader of Fedrigotti’s Bruggler is also reminded of the romantic idealism expressed in the extremely popular war novel Der Wanderer zwischen beiden Welten (1916) by Walter Flex.

32. Bossi Fedrigotti, Anton Graf, Tirol bleibt Tirol. Der tausendjährige Befreiungskampf eines Volkes (Munich: Bruckmann, 1935). Hereafter quoted parenthetically in the main text using abbreviated title Tirol and page number.

33. It is a learning process other films at the time display in very similar ways, for instance Heinz Paul’s Wunder des Fliegens (1935). Here, it is Heinz Muthesius (played by Jürgen Ohlsen, known from his role as Heini Völker in Hitlerjunge Quex) who is obsessed with becoming a pilot like his father. But since his father died on the western front, Muthesius’s mother is strictly opposed. It will take a chance encounter with Germany’s most famous pilot Ernst Udet to convince his mother otherwise. Like Toni in Standschütze Bruggler, Heinz will have his future, however long, on the battlefield.

34. Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf (Munich: Zentralverlag der NSDAP, 1943; originally published in two parts, 1925 and 1927). Hereafter quoted parenthetically in the main text using abbreviated title Struggle and page number.

35. Petersen, Hitler-Mussolini, 496.

36. Petersen, Hitler-Mussolini, 361.

37. See Steininger, South Tyrol, esp. ch. 4. [End Page 77]